The Statement of Decision

Don’t leave a court trial without it!

A Statement of Decision is to a court trial what a verdict is to a jury trial. And just as you would never voluntarily leave a jury trial without a verdict, you should never leave a court trial without a Statement of Decision.

But all too often, attorneys neglect to properly request, propose or object to a Statement of Decision – with potentially disastrous consequences on appeal.

The appellate consequences of failing to perfect a Statement of Decision include:

• Reversal per se if the trial court wrongfully refuses to issue a Statement of Decision (a rule now being reconsidered by the Supreme Court; see F.P. v. Monier; Review Granted, April 16, 2014, Case No. S216566; previously published at 222 Cal.App.4th 187);• Reversal if the Statement of Decision contains material omissions or ambiguities and the appellant preserved the error by properly requesting a s/d and objecting to the form of the document (see, e.g., Shell Oil Co. v. Allied Construction & Engineering Co. (1971) 22 Cal.App.3d 1, 4-5); and conversely,• Affirmance despite defects in the Statement of Decision if the appellant failed to bring those omissions or ambiguities to the attention of the trial court, in which case the appellate court will infer that the trial court made all findings necessary to sustain the judgment (Code Civ. Proc., § 634).

Because the failure to issue a Statement of Decision, and the issuance of a defective one, can both lead to reversal, it is incumbent on the prevailing party − not just the losing party − to participate in proposing, drafting and objecting, so that the document is complete and adequately sets forth all of the trial court’s ultimate factual findings and conclusions of law.

A Statement of Decision serves to pinpoint flaws in the trial court’s tentative decision and can assist counsel in drafting and opposing a Motion for New Trial. At bottom, however, a Statement of Decision is an appellate document. It is the trial court’s report to the Court of Appeal of the reasons for the judgment. It is the roadmap by which the reviewing court finds its way from the pleadings to the evidence to the judgment.

A good Statement of Decision therefore shows the Court of Appeal how the trial judge got from A to Z, and so it is often the first document that appellate court justices, research attorneys, and appellate counsel will read in order to understand the case. In fact, the reason why a defective or non-existent Statement of Decision can lead to reversal is that the lack of a sufficient document impairs the appellate court’s ability to review the judgment. (Gordon v. Wolfe (1986) 179 Cal.App.3d 162, 167-168.)

In short, for the respondent who is defending the judgment, the Statement of Decision demonstrates how the trial court got the facts and law right. For the appellant attacking the judgment, it shows where the trial court went off-course.

Notwithstanding its fundamental importance, however, the procedures for perfecting a Statement of Appeal are byzantine. A first, second or third reading of sections 632 and 634 of the Code of Civil Procedure, and Rule of Court 3.1590 – which govern those procedures – lead only to eyestrain.

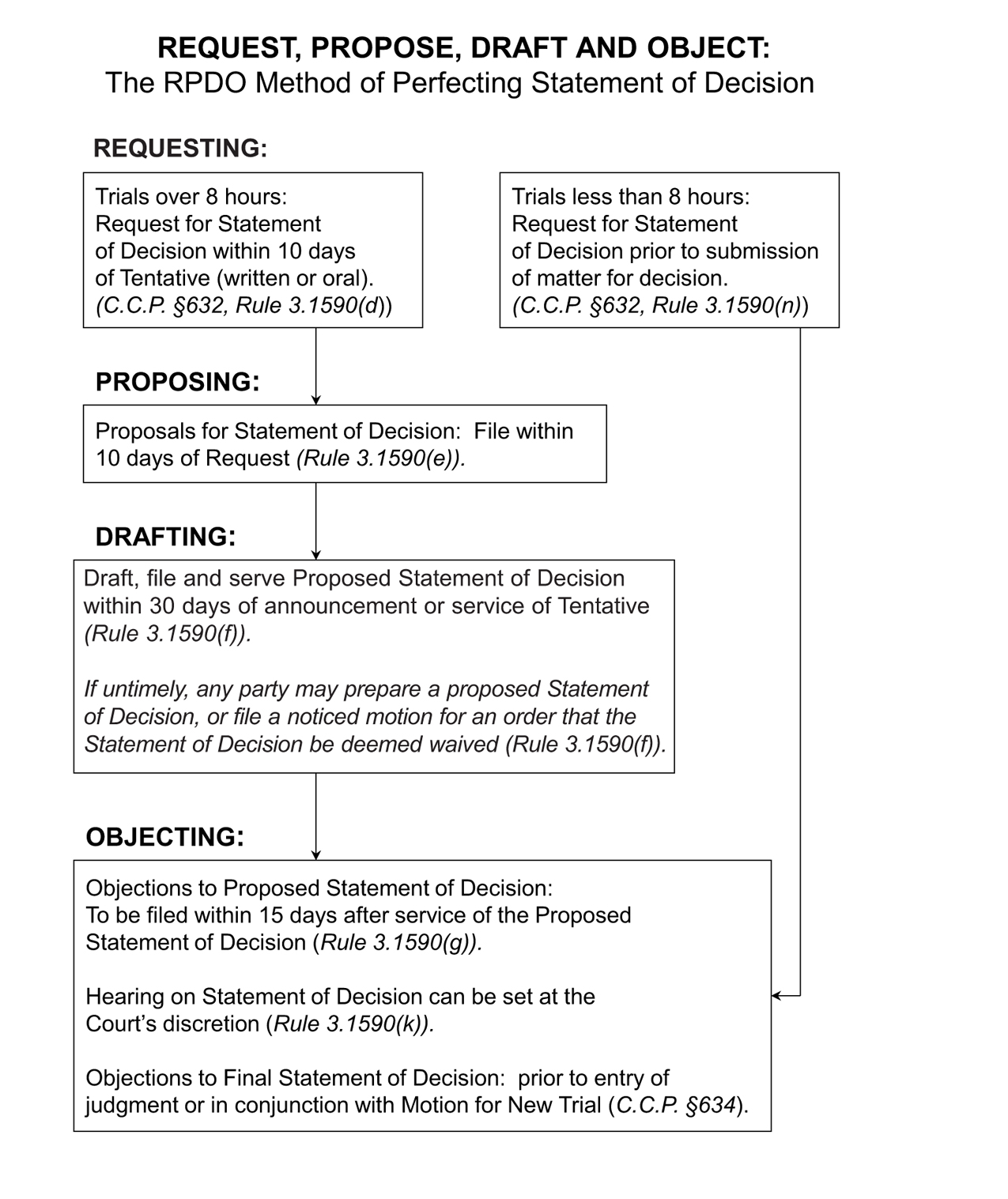

But the procedures for perfecting a Statement of Decision are not difficult to master. They boil down to four basic steps: Request; Propose; Draft; and Object (RPDO), or what I call the “rapido” approach. Each step is critical and a misstep can be deadly to your case – especially a missed deadline (see the accompanying sidebar for an outline of the steps and deadlines).

Factual and legal basis for decision

A Statement of Decision is the document by which the trial court explains the “factual and legal basis for its decision as to each of the principal controverted issues at trial.” (Code Civ. Proc., § 632). It helps correct errors or omissions in the trial court’s tentative decision and can focus issues for post-trial motions. (Miramar Hotel Corp. v. Frank B. Hall & Co. (1985) 163 Cal.App.3d 1126, 1128-29.)

But most importantly, a Statement of Decision is drafted for the benefit of the Court of Appeal, where it serves as the appellate court’s “touchstone to determine whether or not the trial court’s decision is supported by the facts and the law.” (Slavin v. Borinstein (1994) 25 Cal.App.4th 713, 718.)

Enhancing the fundamental importance of a Statement of Decision is the doctrine of implied findings, which kicks into place unless the document is timely and properly requested and unless proper objections are raised to cure deficiencies. The failure to properly request a Statement of Decision, or the failure to bring to the attention of the trial court any ambiguities or omissions in the document, compels the Court of Appeal to infer that the trial court decided in favor of the prevailing party as to those facts or on that issue. (Code Civ. Proc., § 634; Marriage of Arceneaux (1991) 51 Cal.3d 1130, 1136-38). The Court of Appeal will then review the findings for the existence of substantial evidence only. (Michael U. v. Jamie B. (1985) 39 Cal.3d 787, 793.) This is an almost impossible burden for an appellant to carry.

But the doctrine of implied findings applies only to the failure of the Statement of Decision, as a document, to adequately resolve all material issues at trial. The failure to request or object to a deficient Statement of Decision does not affect appellate review of errors of law, which remain preserved. (United Services Automobile Association v. Dalrymple (1991) 232 Cal.App.3d 182, 186.)

RAPIDO made simple

There are four basic steps to creating the right to a Statement of Decision, perfecting its contents, and preserving (and avoiding) the prospect of reversible error.

Requesting the Statement of Decision

Parties are entitled to a Statement of Decision “upon the trial of a question of fact” by the court. (Code Civ. Proc., § 632). They are generally not available to explain an order issued after motion, even if there was an evidentiary hearing. (Marriage of Askmo (2000) 85 Cal.App.4th 1032, 1040.) Exceptions apply, however, and parties might be entitled to a Statement of Decision in motion practice under certain circumstances. (Gruendl v. Oewel Partnership, Inc. (1997) 55 Cal.App.4th 654, 660.)

Your request for a Statement of Decision should be in writing, and the request must be specific. It is not enough to generally request a Statement of Decision or ask that it cover all “controverted issues.” You must “specify” the issues you want covered by the document. (Code Civ. Proc., § 632.) The failure to specify the issues is a waiver of the right to a Statement of Decision, and waives any argument on appeal that the Statement of Decision failed to resolve a particular issue. (In re Conservatorship of Hume (2006) 140 Cal.App.4th 1385, 1394.)

In addition to specificity, timing is key. If the trial exceeds one day or eight hours over the course of more than one day, the request must be made within 10 days of announcement or service of the tentative decision. (Code Civ. Proc., § 632; Rule of Court 3.1590.) Thus if the judge renders an oral tentative from the bench after the close of argument, the deadline to file a request begins to run.

If the trial lasts less than one day or less than eight hours over the course of several days, however, the request must be made before the case is deemed “submitted.” (Code Civ. Proc., § 632; Rule of Court 3.1590(n)). Submission, in turn, is defined as the “date” that the court orders the matter submitted or the date that the final paper is required to be filed or the date that argument is heard. (Rule of Court 2.900(a).)

In short-cause trials, this deadline can creep up on you. Some judges have been known to suddenly announce “submitted” without warning so to cut off counsel’s right to a Statement of Decision. If you know that the trial will last less than a day or less than eight hours, or if you are unsure of its likely length, the best practice is to file a written request specifying the issues before the start of the trial.

Proposals

Once the request for a Statement of Decision is made, any other party has 10 days to file ”proposals” as to the contents of the document. (Rule 3.1590(e).) This is opposing counsel’s first opportunity to begin to shape the document by adding additional material issues that must be resolved, and to massage the resolution of an issue if the tentative decision is weak on that point.

Drafting the proposed Statement of Decision

Once the request for a Statement of Decision is made, the court usually (but need not) direct a party (usually the prevailing party) to prepare a proposed Statement and proposed judgment within 30 days. (Rule 3.1590(f).)

The party directed to prepare the proposed Statement of Decision must file and serve the document within 30 days of the date of the tentative. (Rule 3.1590(f).) If that party fails to file and serve on time, any other party may either file and serve their own proposed Statement of Decision or file a noticed motion for an order that the right to a Statement of Decision is waived. (Rule 3.1590(f)(1,2.) Thus a prevailing party that is directed to prepare the proposed Statement of Decision should do so timely, or else risk turning the task over to the losing party.

The party who drafts a proposed Statement of Decision has an opportunity to control the future direction of the case. At the same time, it is vital not to abuse that opportunity and snatch defeat from the jaws of victory.

A proposed Statement of Decision should not be an argumentative trial brief. Nor need it resolve evidentiary issue or secondary or legal disputes, even if they are specified in the request. The document must instead resolve the material ultimate issues necessary to the judgment, and need not state evidentiary facts. (Hellman v. LaCumbre Golf and Country Club (1992) 6 Cal.App.4th 1224.) Always keep in mind that the purpose is to provide a roadmap of the trial court’s decision. Most often the proposed Statement of Decision builds on the trial court’s tentative decision, corrected for accuracy and amplified with the ultimate, material issues contained in the request.

If you don’t have a tentative to build on, or even if you do, one straightforward approach to drafting a clear and useful Statement of Decision is to use a modified IRAC approach you learned in law school: state the Issue; identify the Rule (law); Apply the facts (findings of fact); and state the Conclusion. Keeping it simple but thorough does the job. If possible, organize the proposed Statement of Decision by cause of action and element by element.

Objecting to the proposed Statement of Decision

Once a proposed Statement of Decision is served, the second most critical step is to object to the contents of the proposed Statement of Decision, specifying any omissions or ambiguities, and to do so within 15 days. (Rule 3.1590(g).)

It is the failure to timely and properly file these objections that can result in a waiver on appeal of issues related to the sufficiency of the document, and invokes the doctrine of implied findings.

But the trick here is to focus on the purpose of the objections. Objections to a Statement of Decision should not be a rehash of the merits of your case, nor an early version of a Motion for New Trial. Nor is it effective to use these objections merely as an opportunity to attack the trial court’s reasoning process. (Yield Dynamics, Inc. v. TEA Systems Corp. (2007) 154 Cal.App.4th 547.)

The focus instead is on the sufficiency of the document as a roadmap of the trial court’s decision. Does the document resolve all of the ultimate issues tried? And, is the resolution of those issues clear and unambiguous?

The issue is not whether you agree with the findings, or even whether the findings comport with the law or evidence. Those are instead arguments for a Motion for New Trial and appeal.

Omissions are easy to spot. If a finding on a material element is missing, it is an omission. For example, “The Statement of Decision fails to determine whether the plaintiff’s reliance on the defendant’s misrepresentation was reasonable.”

Ambiguities are more slippery to pin down, so you have some latitude in the objection. For example: “The findings regarding plaintiff’s damages are ambiguous and inconsistent. The court first finds that the Plaintiff’s lost earning are based on wages only, but later finds that Plaintiff would have been entitled to a significant year-end bonus were it not for the wrongful termination.”

Next, a second round of objections may be necessary if the court issues a final Statement of Decision that resolves some but not all of your objections, or if the final document contains new ambiguities or omissions. In that case, you will need to file a new round of objections either before the entry of judgment or “in conjunction with” a Motion for New Trial. (Code Civ. Proc., § 634.)

At all times keep in mind the dual purpose of the objections. They preserve for appeal the argument that the Statement of Decision is itself insufficient to inform the Court of Appeal of the reasons for the trial court’s Decision, which can result in reversal. Equally important, the objections prevent the Court of Appeal from inferring that notwithstanding omissions or ambiguities, the trial court made all of the findings necessary to support the judgment.

Herb Fox

Herb Fox is a certified appellate law specialist with 39 years of experience in appellate courts throughout the state. His practice includes writs and appeals in a wide variety of civil cases, and contingency fee representation of plaintiffs defending judgments on appeal. More information about Herb can be found at FoxAppeals.com. Herb can be reached at HFox@FoxAppeals.com

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine