A multi-door ADR future

A practical guide to unlocking the full potential of ADR in its many forms

Next April will mark the 40th anniversary of the birth of the modern mediation movement. In April 1976, Harvard Law Professor Frank Sander shared his vision of what came to be known as the “multi-door courthouse.” In his speech, Varieties of Dispute Processing, at the National Conference on the Causes of Popular Dissatisfaction with the Administration of Justice – commonly known as the Pound Revisited Conference – Sander shared a proposal for remodeling the American system of dispute resolution. (Frank E.A. Sander, Varieties of Dispute Processing, 70 F.R.D. 111, 131 (1976).) The litigation world would never look the same again.

When Sander addressed the conference in 1976, nearly all courts offered a single form of dispute resolution: adjudication by judge and/or jury. Sander conceived of a process in which disputes would be channeled through a screening clerk who would direct parties to the process, or sequence of processes, most appropriate to their dispute.

In retrospect, Sander’s observations seem intuitive. In fact, they were revolutionary, forever changing the way that we evaluate the most efficient way to resolve disputes. The most enduring impact of these observations was the advancement and proliferation of mediation and mediation programs, as alternatives to full adjudicatory processes.

In two later refinements of his analysis, Sander sought a means to “fit the forum to the fuss” or the “fuss to a forum.” Through honest and insightful analysis, he sought a model by which counsel could identify the most efficient forum in which to resolve disputes and satisfy the interests of a variety of disputants. His model and taxonomy have led to broad thinking and scholarship in quest of appropriate dispute resolution techniques.

After exploring the history of the “multi-door courthouse,” this article will reflect on the failure of litigators to critically analyze the most appropriate dispute resolution processes for their particular disputes. The remarkable analyses by Frank Sander and his collaborators facilitated the creation of “multi-door courthouses” in only a few jurisdictions. With courts struggling for funding, and the resultant closing of court-annexed alternative dispute resolution (ADR) programs, the widespread adoption of analytical tools to assist litigators in resolving cases cannot be left to a “screening clerk” in a hypothetical courthouse or the power of courts to persuade counsel and parties to adopt alternatives to full adjudication.

Through lack of exposure or a disinclination to engage in the intensely analytical approach laid out in the multi- door courthouse analyses, counsel have intuitively defaulted to mediation in all disputes, without consideration of other alternatives, including hybrid or sequential approaches. Popularizing a simple method to analyze alternatives to adjudication would be welcome. It is hoped that this article will provide litigators with the tools to undertake this analysis, to the mutual benefit of parties, counsel and public institutions.

History of the multi-door courthouse

“Excellence is never an accident. It is always the result of high intention, sincere effort, and intelligent execution; it represents the wise choice of many alternatives - choice, not chance, determines your destiny.” — Aristotle

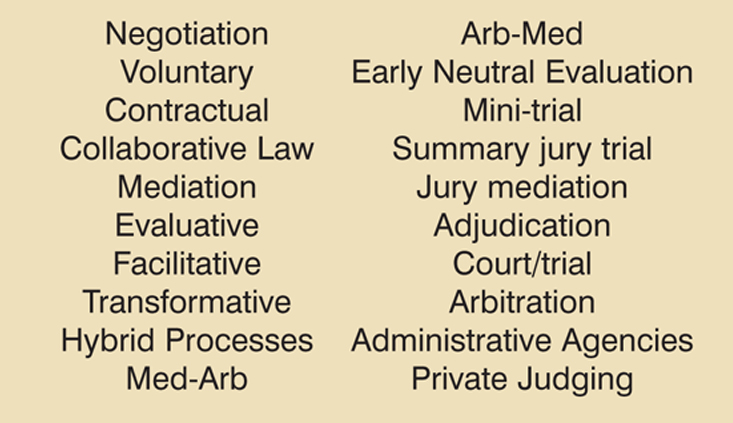

Resolution of litigable controversies can be achieved along a spectrum of dispute resolution processes, from voluntary negotiation to contractual or mandatory adjudication. As will be discussed below, each of these process has a number of variants and is adaptable to individual disputes.

In his 1976 lecture, Sander proposed a “dispute resolution center” where a screening clerk would direct complainants to the process, or sequence of processes, most appropriate to the type of matter involved. Sander asserted that traditional adjudicatory processes handle only certain types of disputes effectively. Some disputes require precedent setting, vindication of a party, fact finding, or legal determinations, and should go to trial. Others might better be resolved by processes such as mediation or a hybrid system.

In 1994, Frank Sander and Stephen Goldberg published their seminal perspective on “fitting the forum to the fuss.” (Frank E.A. Sander & Stephen B. Goldberg, Fitting the Forum to the Fuss: A User-Friendly Guide to Selecting an ADR Procedure, 10 Negot. J. 49 (1994).) The authors identified a number of factors relevant to determining an appropriate means of resolution (e.g., nature of the case, the relationship between the parties, the relief sought, the size and complexity of the claim) and, recognizing that the process was more art than science, sought to evaluate the suitability of various processes from the perspective of the parties (rather than a public policy perspective).

Sander and Goldberg initially proposed to ask counsel about the goals of their clients, and what procedure is most likely to achieve those goals. Counsel would then be asked if the client was amenable to settlement, and what procedure is most likely to overcome identified impediments.

For example, costs are more likely minimized by mediation, mini-trial, summary jury trial, or early neutral evaluation (all discussed below). Such processes would be quicker than trial or arbitration, and afford more privacy than a trial. Relationships are also more likely to be improved or maintained in these consensual processes. In contrast, if the parties seek vindication, a neutral opinion on the facts and/or law, to set precedent beyond the present dispute, or maximize/minimize recovery, trial or arbitration would be preferable.

The authors recognized the flexibility in form and sequencing of non-adjudicatory processes, and as a consequence, the extent to which objectives could be satisfied. Early neutral evaluation (ENE) was a case in point. In its simplest form, an ENE involves an abbreviated proceeding in which an attorney with expertise in a subject area reviews proffers of what the evidence would show and helps the parties reach a resolution, or alternatively, provides an opinion of the likely outcome. If no settlement is achieved, the neutral evaluator may help the parties streamline the litigation process in anticipation of a trial. The viability of this process to result in a valuable opinion varies. If the neutral evaluation follows a full presentation of evidence and argument, it is more likely to be given weight by the parties.

Mediation was deemed the optimal solution in the majority of cases given its speed, low cost, ability to maintain or improve relationships and assure privacy. Mediation permits parties to express their views and vent, as appropriate. Only where parties seek to maximize or minimize the recovery, establish precedent or achieve public vindication, would it seem contraindicated. Moreover, mediation is not a preferred approach where it is necessary to gain an understanding of how the facts will be viewed by a trier of fact, or the law applied by a judge or arbitrator. Where there is room for different factual or legal interpretations, however, a qualified mediator can help the parties assess likely outcomes and to weigh the risks of litigation.

There are also hybrid processes which can achieve these goals. A mini-trial involves convening a hearing panel with a neutral and highly placed settlement officials from each side. Each side summarily presents its case and responds to questions from the panel and the other side. At the end of the process, the settlement officials try to reach a settlement. If they are unable to resolve the dispute, the neutral gives his or her view of the likely outcome of a trial. The parties thereafter attempt again to reach a resolution. A summary jury trial is like a mini-trial, except a mock jury renders its “decision” solely for settlement purposes.

Sander and Goldberg also described what they termed the “jackpot syndrome.” These are situations in which a plaintiff is over-confident in a recovery far exceeding actual damages. While competent mediators regularly move parties to more realistic expectations, a plaintiff suffering from the “jackpot syndrome” may view the cost of full litigation to be justified by the anticipated reward. When all was said and done, Sander and Goldberg posited that mediation would almost always be the preferred process for overcoming obstacles to settlement. Under their proposed approach, if mediation was not successful, the mediator could make an informed recommendation for a different process (e.g., one permitting greater evaluation), followed by a return to negotiations.

In 2006, Sander revisited his approach to matching cases and dispute resolution mechanisms. (Frank E.A. Sander & Lukasz Rozdeiczer, Matching Cases and Dispute Resolution Procedures: Detailed Analysis Leading to a Mediation-Centered Approach, 11 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 (2006).) The authors noted that the most important process choice in the life of a claim occurs when the parties first choose a dispute resolution process. However, this original choice may not continue to be optimal. As conditions change, and information is obtained, it may be advantageous to change procedures.

Rather than describe processes and then matching cases to these procedures, Sander and Rozdeiczer proposed first to analyze the case, including the parties and their goals, and then matching the case to a process, or to design a process to fit the interests of the parties. Since each procedure can take a variety of forms, the authors noted the advantages of adapting procedures to fit the dispute.

Sander and Rozdeiczer revised the factors driving selection of processes by grouping them in three categories: goals, facilitating features (i.e., the attributes of the process, the case, and the parties that are likely to facilitate reaching an effective resolution), and impediments to resolution. In their initial analysis (of goals and facilitating features), the authors emphasized analyzing the case and parties; in the second part (impediments), the focus was on the procedure or forum. An optimal approach involves ranking and weighing the goals. Where the goals of the parties are inconsistent, mediation was the suggested safe approach, unless it is wholly inappropriate.

While evaluating the impact of these factors on process selection, Sander and Rozdeiczer proposed a formula for assigning values, weighing the factors and determining a process choice.

Unlocking the full potential of ADR

“You got to be very careful if you don’t know where you’re going, because you might not get there.” — Yogi Berra

The revolutionary aspect of Sander’s 1976 speech was not encouraging use of processes other than adjudication. The artistry and enduring impact lay in the articulation of the numerous and flexible procedures available for such resolution. Refining that analysis in 1994 and 2006, Sander and his colleagues vividly constructed the “multi-door courthouse,” providing the analytical tools to unlock the potential portals. If counsel are to represent their client’s best interests, what lessons can be learned about ADR?

Nietzsche wrote that “[m]any are stubborn in pursuit of the path they have chosen, few in pursuit of the goal.” The first question counsel should ask in quest of an ADR process is what they and their client are trying to achieve – resolution, discovery, repairing or maintaining relationships, vindication, precedent setting . . .

Mediators ask parties to focus on their “interests.” While facilitative interest-based mediation has become normative, lawyers have a duty to their clients, and to the legal system, zealously to represent the interests of the client, within the bounds of the law. (See, People v. McKenzie (1983) 34 Cal.3d 616, 631.) Coupled with the duty to competently represent clients (California Rule of Professional Responsibility 3-110), it is incumbent upon California attorneys to seek the best forum for resolution of each client’s unique dispute.

While Sander, Goldberg and Rozdeiczer were intuitively correct in advising that mediation may be the appropriate default dispute resolution mechanism, attorneys should undertake a rigorous analysis to assess the proper procedure in each case. Doing so forces reflection on the shifting interests and goals of clients, changes mandated by a client’s business or personal circumstances, and the exigencies of litigation.

Some years ago, I received a call from the General Counsel of two sophisticated media companies. They were calling to say that they wanted me to serve as a mediator in connection with their pre-litigation dispute. The controversy involved highly confidential financial information relating to one party’s claim that the other had failed to pay a fair license fee for a television production due to the fact that the licensor was the parent company of the station with which it was negotiating (a so-called vertical integration claim). As I probed the nature of the dispute, both General Counsel responded with enthusiasm when I asked if what they really wanted was for me to tell them who was right. They had selected me based on their belief that I possessed the requisite experience and ability to render such an opinion.

I asked the General Counsel if they might not be better served by an ENE, rather than progressing immediately to mediation. The dispute had not ripened to litigation, few documents had been exchanged, and no witnesses had been deposed. Both responded positively to my suggestion, and we structured a one-day proceeding in which the parties would present documentary information to me, and to each other, witnesses would present their version of the relevant facts by direct examination. I could ask clarifying questions of the witnesses. And highly confidential information regarding comparable license fees would be submitted to me in camera. We signed an agreement embodying these principles and agreeing to conduct the process under the same strict confidentiality prevalent in mediation.

After a full day of “hearing,” the parties completed their presentations. I asked if the parties and counsel still desired to receive my opinion. One side stated that they understood the position of the other side, and the relevant facts so much better than before the process, that they preferred to move immediately into mediation. The other side rejected that approach and insisted upon receiving a written evaluation. I produced a 15-page, single-spaced evaluation of the merits of the parties’ positions, and my view of the likely outcome of litigation, based on the information provided to date. Armed with this confidential document, the General Counsel met directly and settled the dispute. This was an expeditious, private and low-cost process compared to available adjudicatory options. It resulted in an opinion regarding the facts and law, which the parties found of value. The settlement avoided a public trial and the airing of a dispute which would have cost both sides millions of dollars in litigation expenses, and potentially could have yielded an unwelcome precedent.

The parties were influenced in their selection of a dispute resolution process by reflecting on their interests, goals and objectives.

(1.) Securing a factual and/or legal determination. The parties instinctively sought to mediate their dispute. Their approach was laudable given the pre-litigation status of the dispute. While an “evaluative” mediation might have informed the parties of the risks and potential of the claims, the parties quickly embraced a non-binding procedure which held greater potential for receiving a comprehensive evaluation while simultaneously informing them.

Mediation can take many forms. The thoughtful selection of a mediator to fit the fuss, and the personalities of the participants, is becoming increasingly prevalent. Some conflicts benefit from an “evaluative” mediator who can render opinions and aggressively analyze risks and benefits with the participants. These cases are usually best resolved by focusing on the rights or power of the parties. In most disputes, a more “facilitative” approach is optimal. In such a process, the interests and goals of the parties take center stage as all participants seek a solution which best meets the interests of all. “Transformative” mediation is dedicated to repairing the relationship of the parties, and often involves a primary focus on reconciliation and forgiveness. Different mediators are more or less adept at these distinct forms of mediation, with the majority beginning mediations in a facilitative mode, shifting to more evaluative techniques as closure looms. Fitting the mediator to the fuss, thus becomes vital, and requires more than a default selection of a mediator with whom counsel have successfully worked in the past.

“Collaborative law” processes are well established in the family law environment, and hold promise for use in commercial litigation. In a collaborative law proceeding, the parties sign an agreement stipulating to the use of selected counsel in a confidential settlement process. If that process is not successful, the parties and selected counsel agree in advance that these counsel will not represent the parties in litigation. The result is to remove one perceived impediment to resolution and create incentives for the lawyers to find a resolution to avoid a more costly resolution procedure.

Among other potential procedures which might hold promise in circumstances similar to the licensing dispute are the mini-trial and summary jury trial noted above, and processes known as Med-Arb and Arb-Med. In a Med-Arb process, the parties agree in advance to mediate the dispute with a selected neutral, and if unsuccessful, to move promptly into an arbitration. Arb-Med reverses the process: after a full hearing, the arbitrator seals his or her award in an envelope, to be revealed only if the ensuing mediation is unsuccessful. Both processes bear the potential for informal resolution within the power of the parties, but with a coercive element through which an evaluation is attainable. Neutrals have been historically resistant to Med-Arb and Arb-Med processes, fearing the compromise of confidential communications, inhibition of the incentive for full disclosures which are the hallmark of mediation, and the potential for inadvertent disclosure of the sealed result by probing and reality testing questions. This reluctance has begun to wane, however, in the face of the practical advantages of these party-selected processes.

Prominent ADR providers have created other tools for evaluation in aid of a mediated result. Judicate West has created a process called “Jury Mediation.” With the design aid of the mediator, a jury consultant works with a focus group (jury) to provide feedback on a pending matter, while being observed by the parties and mediator. The American Arbitration Association (AAA) and DecisionQuest have teamed to create an online mock arbitration process in which a panel of AAA arbitrators provides an assessment of pending or prospective arbitrations.

Where a determination of facts or law is required, litigation and arbitration are obvious options. Arbitration takes many forms and the cost can be adjusted accordingly. Despite recent questions about the efficiency and fairness of arbitration, 71 percent of corporate counsel surveyed by the American Arbitration Association believed that arbitration saves money. (See, American Arbitration Association, Dispute-Wise Business Management 19-20 (2003).) Some litigation solutions, such as arbitration, also have the advantage of permitting the parties to select an adjudicator or adjudicators with expertise in the subject area of the conflict.

(2.) Privacy. Trials are public spectacles. Not only is the business of the parties aired for general consumption, but the process carries the potential for inviting claims by similarly situated and aggrieved parties. Mediation, the hybrid processes, and even arbitration are more private enterprises.

(3.) Confidentiality. Privacy’s sibling is confidentiality – the sine qua non of each of the non-adjudicatory processes discussed above. In the ENE described above, the parties were sufficiently comfortable with the neutral that the licensing evidence which was central to the controversy was disclosed only in camera to the neutral evaluator. Beyond the confidentiality secured by statute, the parties may fashion flexible additional protections in appropriate circumstances.

(4.) Cost and Speed. The parties elected the ENE process, and were inclined to mediate their dispute, in an attempt to quickly resolve a potentially costly controversy before investing heavily in litigation expenses.

(5.) Relationship of the parties. One element which impels many to seek non-adjudicatory resolutions is the desire to either repair, improve or avoid further damage to relationships. The “buyer” and “seller” in the ENE process were mindful of the possibility of future dealings. Where parties to a mediation have the potential for future transactions, the process affords far greater prospects for success than one-off pure distributive bargains. Mediation is a useful process to diffuse the anger and emotions which impede settlement. Skilled mediators can help parties overcome unrealistic expectations and shift between “right brain” and “left brain” evaluations.

(6.) Precedent. No benchmarks were established for future dealings between the parties or third parties, by the non-binding evaluation, and later negotiated settlement of the licensing dispute. In contrast, a public trial could potentially create a cottage industry of claims. For example, the ultimate adjudication of the plaintiff’s claims in F.B.T. Productions, LLC, et al. v. Aftermath Records, et al. (2010) 621 F.3d 958 unleashed a torrent of claims challenging whether digital downloads qualified as licenses or sales under prevailing recording contracts.

(7.) Sequential processes. Although the licensing dispute did not formally transmute from an ENE to mediation, the parties took the evaluation which they had initially sought, and used it as a predicate for a negotiated solution. Often, parties will begin with their default choice of mediation, and when stalled, turn to an adjudicatory process for some or all of the issues in dispute. For example, having evaluated the costs and risks of full adjudication during the course of a mediation, the parties may be willing to forego the possibilities of maximizing or minimizing any recovery in court by adopting a form of baseball or of high-low arbitration in which the arbitrator may either award the last best offer/demand of the prevailing party (baseball) or select a result within the high and low range agreed upon by the parties (high-low).

(8.) Maximizing/Minimizing remedies. Court, or an arbitral tribunal, is the ultimate forum for resolution of a dispute when the parties are at impasse based upon potentially unrealistic expectations of one or both parties. When such a result is not required or when the mediator can use cost-benefit or other techniques to close the gap between the parties, mediation is preferable. The increasing prevalence of litigation financing alters this equation and the list of settlement interests which must be satisfied.

While not classically viewed as a mechanism for maximizing gain or minimizing loss, mediation has advantages over trial or arbitration in its ability to “expand the pie” and find solutions not available based on the four corners of a pleading.

Conclusion

“Remember when life’s path is steep to keep your mind even.” — Horace

Ninety-eight percent of civil disputes settle or are withdrawn without a final court decision. Finding the right forum or process to achieve identified goals is thus worthy of counsel’s deliberation. Counsel do a disservice to their clients when they fail to explore the plethora of ADR processes available to them. While mediation may remain the “safe” default, it is not best suited to facilitate the resolution of all disputes. Careful analysis of the interests, goals and personalities of the parties can lead to a contemporary understanding of the most productive process at the pending state of the dispute.

Greg Derin

Greg Derin is a Distinguished Fellow of the International Academy of Mediators, a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators, a member of CPR’s Panel of Distinguished Neutrals, the National Academy of Distinguished Neutrals, and the AAA Roster of Neutrals. Greg is Past Chair of the California State Bar Committee on ADR. From 2004-2012, Greg assisted Professor Frank Sander in teaching the Mediation Workshop at Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation. Greg was named a Power Mediator by The Hollywood Reporter and has been recognized as an ADR SuperLawyer™ every year since 2006. He offers his services through Judicate West.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine