Managing anger in mediation

Anger causes inefficiencies in the process and can result in no deal being reached

Emotions can run high in mediation. This often causes inefficiencies in the process or no deal being reached. Managing emotions, particularly anger, is a skill that can be learned and developed. In this article, we will look at managing anger through: considering the cultural context of anger; a basic understanding of neurobiology; considering reasons why anger should be managed; developing emotional intelligence to beneficially shape how we experience and respond rather than react to anger both in ourselves and in others.

Cultural context of anger

The vivid expression of anger is a dominant element throughout American culture. It permeates our daily lives in journalism, sports, movies, video games, talk radio and political discourse. The aggressive expression of anger, as righteous indignation or revenge, is extolled by the cheers of audiences whether in theaters or political rallies.

The expression of anger is generally not considered to be a problem in American culture. To the contrary, venting rage is widely thought to be healthy if not expected when confronted with something that is considered offensive. This holds true in respected quarters of the mediation community, where mediation is considered to precisely be a forum for venting emotions.

While the recognition of the emotional drivers in a conflict can be an essential element to reaching a resolution, the unchecked expression of anger in a mediation often derails the productive handling of issues in dispute, sidetracks the process, leading to an impasse. Whether or not the expression of anger is considered to be beneficial in the mediation context, the management of anger most certainly is.

Mind and brain

Our mind fundamentally arises from the functioning of our brain. We often experience conflicting thoughts and emotions, with consequences that are not beneficial. Awareness of the basic structures of the brain and their functions illuminates this process, allowing us to develop ability to consciously respond rather than impulsively react to emotions.

The triune brain

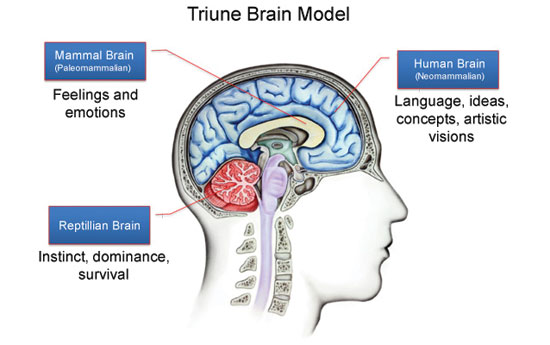

Our brain has three central areas that are the result of evolutionary development.

The Human Brain is the structures involved in rational, conceptual and imaginative thought.

The Mammal Brain is the structures involved with emotions and social behavior.

The Reptilian Brain is the structures related to territoriality, aggression, dominance and ritual behavior.

Our mind arises largely from the simultaneous operation of those three brains. This explains how it is that in the midst of important, rational interactions with other people, basic impulses can distract us. The Human Brain becomes overwhelmed by impulses coming up from the Reptilian Brain and/or Mammal Brain.

For example, just after a two-car accident, in the midst of exchanging basic information, one or both drivers may take umbrage with what the other is saying or how they are saying it, with an impulse to become verbally abusive or physically attack the other, even though there is no benefit to come of that.

Litigators often see this process in the midst of encounters with opposing counsel, such as in deposition. Without anyone present to temper behavior, lawyers tend to act out, which escalates into an unproductive exchange of tirades that is ultimately of no benefit. Anger usually plays a dominant role in those exchanges.

In mediation, we often see this even when the sides are in different rooms. The mediator relays to one side how the other side sees an issue and the discussion quickly turns into a series of emotional outbursts by the lawyer, the client or both, dominated by anger.

Lawyers often strategically invoke anger in mediation, for the intended purpose of gaining leverage from the mediator communicating that anger to the other side. This behavior is reinforced by the client’s gratitude at having a tough lawyer and more so when the mediation results in settlement. You might wonder, if being tough and angry in mediation works, why bother doing otherwise?

Why bother managing anger?

This comes down to what kind of life you want to live and the world you want to live in. It also affects your results and referral stream.

Being angry is exhausting. It wears on you and the people around you. While there may be a certain satisfaction from venting, it does not make you and others happy. When you spend the day being angry, this affects how you are when you get home at night. Please take a moment and reflect on that.

In the mediation context, while anger cannot be avoided, it can be controlled. Unchecked anger leads to impulsive rather than rational positions. Unchecked anger is a powerful distraction, drawing attention away from the nature of the issue at hand, producing the impulse to attack the people on the other side rather than engage in constructive problem solving.

Anger thereby becomes the point rather than a tool or momentary distraction. Unchecked anger often does not constructively ventilate; rather it stimulates the Mammal (emotional) Brain, causing more anger, not less.

This has a cascading effect. It is viewed as being disrespectful, invoking unproductive defensiveness and counterattack, reminiscent of schoolyard days: “I know you are, but what am I?” Moreover, anger prevents participants from absorbing and using information being exchanged, because anger causes us to interpret information to fit how we feel, ignoring that which does not fit our feelings.

Even without anger arising, we have a natural tendency toward confirmation bias, which is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms our preexisting beliefs. Confirmation bias is particularly present when we want things to turn out a certain way. Confirmation bias contributes to overconfidence in a personal belief and can maintain or strengthen beliefs in the face of compelling contrary evidence. We see this often whether in our family lives, the electoral process or in mediation.

You have seen this in your own practice or those of your colleagues: an opportunity to resolve a matter which was rejected on the basis of what turned out to be wishful thinking. It is one thing to take a chance based on sound reasons and evidence. It is quite another to reject a deal because you are emotionally attached to a preconception that turns out to have little or no foundation in reality.

Anger amplifies confirmation bias. Therefore, keeping anger in check lessens the effect of confirmation bias and allows you a broader opportunity to reach settlement at mediation, based on reasons that are better articulated, understood and accepted by your client. This leads to a more durable resolution, in that it lessens the likelihood of getting that dreaded phone call from your client the day after the mediation, telling you to get them out of the deal.

More durable settlements are more satisfactory to your client which naturally leads to more referrals, not only from your client, but from others involved in the mediation. As a full-time mediator, I am often asked for referrals to practicing lawyers. My tendency is to refer to those lawyers whom I have seen being calm and gracious under fire, not the hot heads.

Managing anger with emotional intelligence

Strong emotions, including anger, can be effectively managed though the development and practice of emotional intelligence. Emotional intelligence is the ability to monitor one’s own and others’ feelings and emotions, to discriminate among them and to use this information to guide one’s thinking and actions. While emotional intelligence is an entire subject in itself worthy of study, here are some basic practices which you can begin using right now to manage anger.

Emotions register in your body. Emotions are physiological responses to relevant situations. This means that emotions are expressed as changes in our bodies. See it now for yourself:

- Bring up a feeling of being angry. Picture something that recently set you off. You are tense, you are upset, things are not going your way. Give that a moment to register.

- Where do you feel that in your body? Take a moment to fully notice that.

- Now bring up a feeling of joy. A sunset, or the open smile of a child, you feel a sense of warmth and freshness. Give that a moment to register.

- Where do you feel this in your body? Take a moment to fully notice that.

Usually, these physiological responses occur before our Human (thinking) Brain fully recognizes what is happening. Our body is sending us valuable information about our emotional state, but we are not paying attention to that.

Developing active, intentional awareness of physiological responses is the basis for emotional intelligence. When we apply this awareness to emotional sensations, a liberating shift can happen: we can move from “I am my emotions” to “I experience emotions.” Practice at this and then it increasingly becomes: “I beneficially control my response to my emotions and those of others.”

Anger often registers as a quick, strong emotional reaction, referred to as “being triggered.” We quickly go from feeling in control and aware, to being highly reactive, often unable to stop ourselves from saying or doing something that we sense will cause problems later on. We sense the Human Brain being hijacked by the Mammal Brain and let it happen as if we have no control.

Signs that you have been triggered might include a sinking feeling in the stomach, tightness in the shoulders or face, an increased heart rate – we each have our own patterns.

There is nothing wrong with you when that happens. This is a primal, hard-wired behavior pattern that evolved to protect us from threats. And it still works really well if your physical safety is actually threatened: it can quickly drive your mind and body into action to get out of the way of an oncoming bus. It would not help to pause and reflect on what is happening; that is why the Mammal Brain simply hijacks the Human Brain – shoving it aside so that you can quickly respond to the threat to your physical safety.

This primitive pattern operates not just for physical threats to our survival, but also for perceived or imagined threats, even when they are not physical, but simply contrary to our perceived interests. For example, obstreperous opposing counsel in a deposition or court hearing. What that lawyer is doing is not a physical threat to us, yet we experience it as one, and get triggered.

When we get triggered, we tend to think and act as if we are fighting for survival. We narrow our focus, act quickly, becoming combative when a more skillful response is possible. Please see this for what it is: a primal, survival response mechanism that gets inappropriately activated in modern settings. Here are four specific steps you can take to use awareness of this pattern to actively manage anger.

- Notice. Notice how anger feels in your body. Anger has distinct physical markers: involuntary facial expressions; tightness or swelling of the neck; quickness of breath; increased heart rate and blood pressure causing a sensation of heat; tightening of the abdomen. The first step to checking anger is to practice simply noticing when one or more of these markers arise.

- Breathe. Intentionally slow the anger process down. Once you notice the physical markers of anger arising, take from one to three deep, full breaths. The simple practice has two immediate benefits: it calms the body, thereby slowing the anger process down; it allows you a moment to see the anger – and what caused it rather than simply reacting to it. This is referred to as the “sacred pause.” The breaths must be deep and full, both the in-breath and out-breath. Anger causes shallow breathing. So to be effective in disarming anger, your “sacred pause” breaths must be extraordinarily full and deep.

- Reflect. Briefly reflect on the humanity of the other – “just like me.” Remember that the person who has caused your anger to arise or who is expressing anger is just like you: a human experiencing the full range of joys and challenges of being human. They have a job they are trying to do; a goal they are trying to reach; they make mistakes; they have habits; they have biases; they act out of emotion at the expense of rational thought; perhaps they do not intend to be offensive. You can sum this up by simply saying to yourself in that moment, “just like me.” This naturally leads to feeling compassion for the other. Don’t worry; it doesn’t mean you condone what they are doing or that you are not zealously representing your client. It just means that you are being more fully and constructively human.

- Mission. Refocus on your mission. Having slowed the anger process down and having reminded yourself that your antagonist is simply doing what people just like you do, ask yourself if the reaction that your anger indicates is beneficial to or does it detract from your mission – which is to get the best possible deal for your client. It’s not about you. It’s not about showing up the other side. It’s about your client.

Managing anger is a practice, not just an idea

Like any practice, your ability to manage anger gets better over time. The more often and consistently you try, the better you get – and eventually managing anger becomes a habit. This is a function of neuroplasticity: changes to the brain which occur from repetition of activities, resulting in new neural connections which fire together in response to what is happening in your perceived world. Through practice, you literally can cause new brain cells to grow and function in a certain way. You can let go of habits that do not serve you and acquire new habits that do. Please do not wait until you are in a mediation to practice. Here are some ways to begin practicing now.

- Notice anger arising when watching a sporting event or a movie. Whether or not you are one who yells at the TV or movie screen, like everyone else you feel strong emotions if you are engaged by the spectacle. Why not get a twofer out of it: enjoy the spectacle and practice emotional awareness. Maybe take it a step further and practice not acting out in response to what you are experiencing. This is as easy as it gets since you are not actually participating in the event.

- Notice anger arising when driving. This takes it up a notch. Now you are involved in the event. If you are a litigator, chances are pretty good that you are an aggressive driver or at least one who does not suffer fools on the road lightly. Do you get furious when cut off? When someone busy texting does not notice the light has changed causing you to miss the light? These are excellent opportunities to practice fully what you have learned in this article. Notice anger arising; take an extraordinary breath in and an extraordinary breath out; remind yourself that they are “just like me”; notice that the anger will not serve you, so just let it go.

- Notice anger arising at the office. This takes it up another notch. Now you are in the three ring circus: dealing with opposing counsel, partners, associates and staff, court staff, witnesses, vendors – often in some combination. Do the practice; then the circus is just a circus. Do the practice some more and then it’s not a circus, it’s just your office. Keep doing the practice and you may open up some space to experience the joy in it.

- Notice anger at home. This takes it into another universe. Family relationships are perhaps the toughest to deal with if you have difficulty managing anger. It may be easier for you to manage anger at work than at home. Do the easier exercises first. Get comfortable with that. Imagine if you were a bit kinder at home. Then slowly, gently practice in this realm. It’s worth a try, isn’t it?

Conclusion

We are not merely products of our culture. We can choose the extent to which we participate in its myriad aspects, including how we deal with anger. Anger is an emotion subject to habit. You can practice letting go of habits that do not serve you and learn new habits that do. It takes some time and patience to accomplish. For the sake of your own wellbeing and that of those around you, please make the effort to see anger for what it really is and transform it into something else, something beneficial, like compassion.

Mark Fingerman

Mark Fingerman is a mediator with ADR Services, Inc., with an LL.M. in Dispute Resolution. He specializes in business litigation, personal injury, insurance and intellectual property. He is a certified yoga and meditation teacher, trained by Search Inside Yourself Leadership Institute (Google offshoot) in teaching mindfulness-based emotional intelligence. In his off hours, he teaches functional mindfulness in companies, professional services firms and to individuals, meditation at UnPlug Meditation (Los Angeles) and yoga and meditation at Santa Monica Power Yoga. More at www.FingermanMediation.com; www.MarkFingerman.com. Contact at mfingerman@adrservices.org.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine