Navigating the court during the COVID-19 pandemic

The Mosk courthouse may be open, but you may not want to come here

There are indelible events in our collective memories. We remember exactly where we were in 1963 when we learned that President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. We recall sitting with our family in front of the television watching in awe as two men landed on the moon in 1969. We remember staring at our television sets in disbelief as two commercial jetliners flew into the World Trade Center towers on September 11, 2001.

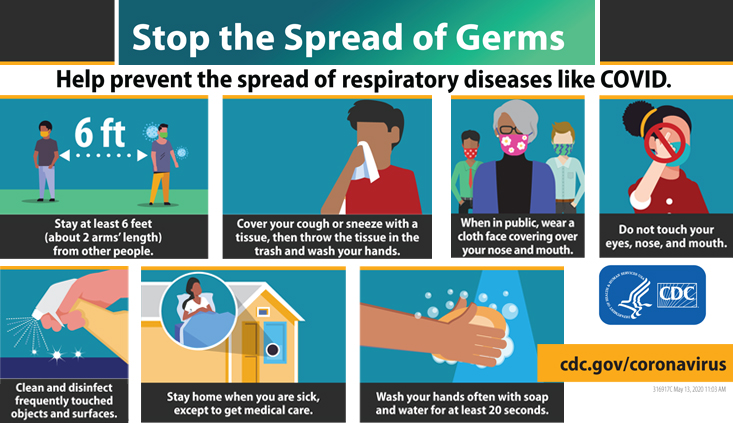

As we live through the COVID-19 pandemic, we are collectively experiencing such an indelible event. At first, we watched the horrifying events in Wuhan. Cases spread across the globe and, on March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared a worldwide pandemic. We have experienced an economic sudden stop, food, ventilator and personal protective equipment shortages, heartbreaking scenes from hospitals, deaths of health-care workers and people dying alone, isolated from loved ones. Lockdowns were imposed to flatten the curve. Social distancing and facemasks are required in public.

The Los Angeles Superior Court ceased normal operations on March 17, 2020, and will begin to ramp up operations when the court reopens on June 22, 2020, a 96-calendar-day period. With unprecedented speed, lawyers and courts have reimagined and reengineered the practice of law and court functions. We became proficient in Zoom and Webex as we worked from home. This article addresses how court operations may evolve as we learn together how to navigate in the Los Angeles Superior Court during the COVID-19 pandemic. The views expressed in this article are those of the author, not the court.

Courthouse safety, social distancing and facemasks

Due to space limitations, the Mosk courthouse was not safe even for normal, pre-pandemic courthouse operations. There is no herd immunity to COVID-19, no safe and efficacious vaccine and no reliable, interpretable antibody test. Social distancing and facemasks are required.

Upon reopening, it is hoped that the Mosk Courthouse will be a ghost town. The court is strongly encouraging remote appearances and strongly discouraging in-person appearances. The court is not large enough to conduct business as usual while maintaining six-foot social distancing. For example, current signage limits occupancy in Mosk Courthouse elevators to two persons at a time. There are six-foot markers in front of the elevator banks. It would be dangerous to have stairwells filled with people not maintaining social distance, some of whom might be huffing and puffing while climbing up the stairwells. Lawyers hurrying to their appearances may not wait to get on the escalators at six-foot intervals to maintain social distancing. Court restrooms are not conducive to social distancing.

The facemask issue

Facemasks may be a constant and problematic issue in the courthouse, just as they are outside the courthouse. Current court policy requires facemasks at all times in the courthouse unless there is an Americans with Disabilities Act issue or medical reason. Persons exempt from the facemask requirements may enter the courthouse only at the specific time for their appearance for the sole purpose of having their matter heard. Their cases will be last on calendar and the courtroom may be cleared when their matter is heard.

COVID-deniers and others may not want to wear facemasks for non-medical reasons. While we are accustomed to signage on businesses such as Costco prohibiting entry without a facemask, we have also seen security guards and store employees attacked while attempting to enforce facemask policies. Unmasked persons in the courthouse may frighten jurors and others.

People who do not understand courthouse signage may also present compliance issues. Others may have facemasks around their necks, not covering their mouth and nose and some may remove their facemasks to speak. We have seen this in our daily lives.

Older and high-risk persons may not feel comfortable in restrooms, courtrooms, hallways, escalators and elevators with unmasked persons. Many attorneys and one-third of our judges are over 65 and are considered a high-risk population. Judges will have varying levels of sensitivity to unmasked persons.

“Having witnesses provide testimony while a portion of their face is covered by a mask would represent a significant departure from the face-to-face engagements that were the norm in prepandemic times.” (CJEO Oral Advice Summary 2020-032, Judicial Obligations Regarding Witness Facemasks During the COVID-19 Pandemic.) Will parties and witnesses be required to remove facemasks while testifying even if they are reluctant to do so? Criminal cases involve the Sixth Amendment right of confrontation and civil cases do not. But all litigants are entitled to have their matters fairly adjudicated in accordance with the law. (Id. at n. 2.) Will witnesses testifying while wearing facemasks impede the jury’s ability to determine credibility?

Will jurors remove their facemasks while being questioned? Will attorneys wear facemasks when questioning a juror, examining a witness or making an opening statement and closing argument? Many jurors may be familiar with how long coronavirus stays in the air and how far it travels if someone is talking or shouting. If attorneys are unmasked, will jurors be frightened?

Does the court policy, as of this writing, requiring all persons, including witnesses, parties and attorneys, to wear facemasks at “all times,” prevent the trial judges from granting a request to have a witness remove his facemask while testifying? How will the Court of Appeal view an order denying such a request based on “court policy” instead of analysis of applicable law? Will the result differ depending on whether it is a civil or criminal trial?

The signage in the courthouse is due for an update after the cutoff date for this article, so it is not possible to comment on any future signage or physical installations. The changes to court operations are a work in progress. Having observed the court’s efforts at social distancing signage in the courthouse during the lockdown and the space limitations throughout the courthouse, the author strongly recommends against coming to the courthouse at this time. Conducting business as usual is not possible, as courthouse and courtrooms are not large enough for social distancing.

Remote appearances and the new LA Court Connect

Remote appearances in civil courts are available from Court Call, the company that pioneered remote appearances in the court. The Los Angeles Superior Court’s pre-pandemic plan was to implement, over a period of 18 months, an audio and video appearance system, LA Court Connect. The pandemic compressed that time frame, and LA Court Connect is scheduled to be operating in probate courts and civil settlement courts on June 22, 2020. LA Court Connect will be phased into civil courtrooms sometime after July 13, 2020.

A new attorney portal will serve as a one-stop place to access LA Court Connect and other resources. Beginning on June 7, 2020, attorneys may create their Court ID through the attorney portal. Beginning on June 15, 2020, attorneys may schedule remote appearances for probate and civil settlement courts only through the attorney portal.

Until Court Call is phased out, Court Call’s existing remote appearance services will remain available at a cost of $94, a rate set by the California Rules of Court. LA Court Connect fees will be $15 for an audio appearance, $23 for a video appearance and no charge for persons with fee waivers. LA Court connect will reduce the number of court visitors, save commuting time, eliminate parking and driving costs, and help the environment.

In the courtroom, handing cards, courtesy copies or other papers to the judicial assistant will be a thing of the past. Walking up to the judicial assistant and standing at the edge of his desk will not be permitted with six-foot social distancing.

In pre-pandemic times, attorneys were reluctant to appear by Court Call for hearings on major motions. You could not see the judge’s face and observe your opposing counsel with audio Court Call. Video Court Call was almost never used. With LA Court Connect, the plan is to show the judge and only those persons appearing on the case when the matter is called. Just as on a Zoom conference, LA Court Connect will afford users a better view of the judge and opposing counsel’s face. Attorneys will not feel as though they are missing something by appearing remotely on LA Court Connect and it is hoped that the bar will feel comfortable appearing remotely on LA Court Connect.

Which jury trials go first?

All criminal, unlawful detainer and priority civil cases have some form of priority or preference and are entitled to jurors and trials before other civil cases, including cases in the Independent Calendar (IC) courts and the Personal Injury (PI) hubs. However, there may not be enough jurors or courtrooms for all of the trials.

There are 66 IC courtrooms countywide, 42 in Mosk and 24 in the districts. There were 88,500 unlimited civil cases pending, including personal injury cases, as of March 31, 2020. The current plan is for IC judges to split their calendars into four time slots, two in the morning and two in the afternoon, so law and motion can be heard throughout the day utilizing social distancing. The IC courts will likely have limited availability for trials while this protocol is in effect.

There are 28 trial courts countywide. Civil priority trials will go out first and will be sent to the trial courts. However, getting jurors for the civil priority trials may be problematic.

The criminal case backlog has been referred to as a “mountain of criminal trials.” Criminal trials have priority over non-priority civil trials and UD trials, so jurors will likely go to criminal trials first.

Misdemeanor and felony criminal cases with charges that carry jail or prison sentences may be entitled to priority over civil preference cases, as criminal trials involve a constitutional liberty interest and civil priority is statutory.

Civil statutory trial preference may trump unlawful detainer statutory precedence. Unlawful detainer trials are entitled to unqualified precedence over all other civil cases “except actions to which special precedence is given by law” and must be set for trial within 20 days of a request to set trial. (Code Civ. Proc. § 1179a.) There is no such qualifying language in the civil preference statute. Code of Civil Procedure section 36 provides that priority cases based on age or illness shall be set for trial no later than 120 days after the motion for preference is granted. No trial continuances are permitted except for the physical disability of the party or attorney, and continuances are limited to one 15-day continuance.

Criminal cases utilize more jurors than civil cases. In a one-defendant felony trial, each side is entitled to 10 peremptory challenges for a total of 20 peremptory challenges. If there are two or more defendants, each side is entitled to 10 peremptory challenges, each defendant gets five additional challenges, and the prosecution gets an equal number of peremptory challenges. Thus, 40 peremptory challenges are permitted in a two-defendant felony trial. In a one-defendant “to life” sentence case (i.e., 25 years to life) and death penalty cases, each side is entitled to 20 peremptory challenges, for a total of 40 peremptory challenges. In a two-defendant “to life” case there are five additional challenges per defendant, and the prosecution gets an equal number. Thus, in a two-defendant “for life” case, 60 peremptory challenges are permitted. (Code Civ. Proc., § 231.)

Civil judges will likely handle criminal arraignment and trials to help with the criminal backlog. Approximately 30 judges are being cross-trained to handle criminal arraignments and trials.

Court reporters are required for all criminal hearings and trials. Court reporters in the criminal courts were not laid off during the budget cuts. If judges assigned to criminal courts are handling criminal trials and are working at capacity, there may not be enough court reporters to send criminal cases to all of the open civil trial courts. There are no lockups in the Mosk courthouse, so it is unlikely that serious criminal cases will be handled at Mosk, but civil judges could be sent to the Foltz or another courthouse to handle criminal trials.

Unlawful detainer trials are jury trials and have statutory precedence. There are three dedicated unlawful detainer trial courts in the Mosk courthouse. The 28 trial courts handle overflow unlawful detainer trials. There were 10,550 unlawful detainer cases pending as of March 31, 2020. It has been reported that there are 2,000 pending unlawful detainer cases with jury trial demands. When the moratorium on filing new unlawful detainer cases is over, there may be a large number of unlawful detainer cases filed.

There were 98,265 limited civil cases pending at the end of March 2020. There are no courtrooms dedicated to limited trials. Jury trial waivers are common in limited cases, and occasionally limited civil cases are sent to the open trial courts.

Small claims cases

Small claims cases are bench trials and will not resume until July 13, 2020. Parties in small claims cases may be reluctant to come to the courthouse. Given the number of litigants who appear in small claims cases, hearings in small claims matters will be delayed until LA Court Connect is implemented and the court has developed a protocol for submission of exhibits in advance of the hearing either by mail or electronically. Until remote hearing technology is implemented and adopted by small claims litigants in a meaningful way, the number of matters will be limited to five cases per session, with four sessions per day. As of this writing, no cross training for civil judges has been offered for small claims trials, and it is not anticipated that small claims trials will be sent to open trial courts.

Traffic trials are bench trials. Civil judges are being cross-trained in traffic trials, and traffic trials may be sent to open trial courts.

The backlog of criminal and unlawful detainer cases, potential juror shortages, courtrooms not large enough for six-foot social distancing in many civil jury trials present nearly insurmountable challenges to conducting jury trials in non-priority civil cases for the foreseeable future. There is sure to be a significant backlog of civil jury trials to work through when it is safe for operations to return to normal.

Budget cuts

While outlook for conducting civil jury trials is bleak, significant budget cuts appear to be on the horizon due to COVID-19 pandemic spending. Budget cuts may exacerbate current challenges.

Location of jury trials

When there are enough jurors to conduct jury trials, where will the trials be held? A limited number of large courtrooms might be utilized for jury selection only. But in the typical Mosk courtroom, many jury trials may be a squeeze with six-foot social distancing.

The air circulation system in Mosk was installed when the courthouse was constructed in the 1950s. Black substance can be seen around the air circulation vents on the ceilings in many courtrooms and chambers. The air circulation in the courtrooms and hallways may not be optimal. It may be prudent to rethink spending many hours a day in the smaller courtrooms in the Mosk courthouse, even with social distancing.

Juror availability and demographics

Pre-pandemic, for every ten jurors summoned, three jurors appeared on call or in person, according to published Los Angeles Superior Court statistics. No jurors have been summoned as of this writing and we do not know how many jurors will appear for jury duty during the pandemic. Some anticipate that fewer jurors will appear in response to their jury summons, making jurors a very scarce resource. It is likely that jurors will be allocated according to statutory trial priority.

Pandemic juror demographics may shift in comparison to pre-pandemic demographics. Older persons are acutely aware that their age places them at greater risk of death and serious disability if they contract COVID-19. Continuously, the public has been warned of significantly higher death rates and poor outcomes in older persons. Persons over 65 and those at high risk were told to shelter in place. Many older Californians were taken aback or even frightened when the California governor told physicians to incorporate a “life cycle principle” into their medical decision-making. The “life cycle principle” allocates to younger persons priority access to scarce medical resources, including ventilators. The young are given priority over the old because younger people have had the least opportunity “to live through life’s stages.” After negative reaction, the governor reversed his position. (See, e.g., Tony Coehlo, Rationing COVID-19 Treatment to the Elderly and Disabled is Illegal and Immoral, Los Angeles Times, April 30, 2020.)

Fewer older persons may appear for jury duty in proportion to younger jurors. If so, the pandemic jury venire may have a greater number of younger jurors in comparison to pre-pandemic jury venires. Attorneys on both sides of the aisle have expressed reservations about trying their cases to a “jury full of millennials.”

Juror attitudes

Assuming you are able to get a panel of jurors for your trial, how will juror attitudes have changed since the onset of the pandemic? The legal community and jurors have learned about coronavirus, the transmission of infectious disease, how long the coronavirus remains in the air, how far it travels depending on whether the person is speaking, shouting or sneezing, how long coronavirus remains on surfaces, fomite transmission, viral loads, N-95 facemasks, comorbidities and death rates. We have seen the animation of a person sneezing in one aisle of a grocery store and the droplets going over the shelves onto persons into the next aisle.

The pandemic may have caused sudden shifts in juror attitudes, including attitudes about being in a courtroom for the better part of a day, surrounded by persons in facemasks. There will be uncertainty involved in early jury trials, as we all learn together whether some of the current theories are valid, such as whether jurors who are not afraid to appear in court will be better for the defense and whether jurors who are afraid to appear in court will be better for plaintiffs.

Settlement

This may be a good time to rethink settlement and discuss the changed circumstances with your clients. You may wish to participate in a Webex settlement conference with the LASC settlement judges, a remote settlement conference with a private mediator or a Zoom settlement discussion with your opposing counsel.

Speedy civil trials

Jurors will likely be uncomfortable sitting in courtrooms. Outside the Mosk courtrooms, jurors will probably stand in the hallway, as the benches can accommodate only two people with social distancing.

It will be imperative to conduct your voir dire and trial swiftly and efficiently. Judges who indulged lawyers who wasted time may not do so now. Voir dire in smaller courtrooms will have to be conducted with small groups of jurors, and attorneys should be prepared to use time effectively.

Bench trials: Go to the head of the line?

Given the criminal and unlawful detainer trial backlog and juror reluctance to serve at this time, there will likely be a large number of open courts among the 28 trial courts. It is likely that bench trials will be sent out first.

You may wish to consider a bench trial soon after the court reopens rather than waiting a year or more for a jury trial. Consult your client and opposing counsel. Try to stipulate to a few civil trial judges for a bench trial if the case is sent out for trial promptly, waiving your peremptory challenge as to those judges. You might also consider a bench trial with a high-low agreement.

The right to a jury trial may be waived by written consent filed with the clerk or judge or oral consent, in open court, entered in the minutes. (Code Civ. Proc., § 631, subds. (f)(2), (3).)

Agree on a plan for handling documents that does not involve handing them to the judicial assistant and the court, such as providing PDF documents on a jump drive. Be sure each page is marked with the exhibit number and page number. Remember that court technology is basic and judges may not have access to many programs that you may have.

You may find that the trial court judges are extremely familiar with jury verdicts and the value of a case. Experienced judges will likely have conducted numerous bench trials, as jury waivers are not unusual in commercial and other disputes not involving personal injury.

Having conducted numerous bench trials during the course of more than 26 years, it is the author’s view that bench trials in state court are easier, more relaxed, less stressful, involve less preparation and are less risky than jury trials. Your clients will not be under a microscope in the halls and restrooms and outside the courthouse. Your trial will not be decided based on odd, extraneous matters. You will have a conversation with the judge about the evidence in closing argument, and you may get questions during closing argument that will help you more effectively argue your case. Bench trials may be suitable for remote trial technology when it becomes available.

No jury instructions are needed in bench trials, eliminating any appeal based on instructional error. A verdict form is not required. In the average case, giving the court the applicable CACI numbers and an opening statement will suffice. Typically, motions in limine are not necessary. An oral motion in limine can be made at any time during trial, and judges are excellent at compartmentalizing and not considering inadmissible and excluded evidence. Judges may ask questions, but ordinarily should not examine the witness until the parties have completed questioning the witness. (LASC Local Rule 3.134.)

You may ask to file a post-trial brief or submit jury verdicts in similar cases. Judges may decide the case orally from the bench or announce a tentative decision from the bench and take the matter under submission. (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.1590(a).) Counsel may request a written statement of decision. (Code Civ. Proc., § 632; Cal. Rules of Court, rule 3.1590.) When the trial is concluded within one calendar day or in less than eight hours over more than one day, the statement of decision may be made orally on the record in the presence of the parties. (Code Civ. Proc., § 632.)

If a statement decision is requested, the court may ask for proposed statements of decision (PSOD). A PSOD should set forth the elements of the claims or defenses, demonstrate how the plaintiff or defendant did or did not meet the burden of proof. You may ask to file a response to your opponent’s PSOD.

The court will issue a PSOD and the parties may file objections to the PSOD. Parties are entitled to a hearing on their objections. The court will issue a final statement of decision (SOD) and judgment. The PSOD may provide that if no objections are filed, the PSOD becomes the final SOD.

Conclusion

It is hard to imagine when most civil jury cases will be tried, given statutory priorities, the backlog of criminal and unlawful detainer cases, juror shortages and courthouses not designed for social distancing. Alternatives include bench trials, settlement conferences and mediation.

Mary Ann Murphy

Judge Mary Ann Murphy has served on the Los Angeles Superior Court since 1993 and sits on the bench for a trial court at the Mosk Courthouse. She has moderated the central civil courts’ Best Practices discussions since its inception in December, 2005. She was an associate editor for Weil and Brown, Civil Procedure Before Trial for seven years. She served on the statewide Civil and Small Claims Committee and served four terms on the court’s executive committee. Judge Murphy is actively involved in educating judges and lawyers and is a frequent speaker.

Endnote

Navigating the court during the COVID-19 pandemic

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine