Now what?

Unusual conundrums during pendency of an appeal

Appellate attorneys often receive calls from trial counsel seeking assistance in navigating unexpected and unusual procedural challenges. Sometimes, however, even the most seasoned appellate attorney encounters surprises while a case is pending resolution by the appellate court. This discussion offers guidance for anyone navigating similar waters in their own appeals.

Early dismissal

Sometimes, whether due to the nature of the claim or the subsequent representative, continuing the appeal is no longer desirable. The necessary steps to terminate an appeal depend on whether the appellate record has been filed, and prior to taking steps to prematurely end the appeal, it is important to consider the implications of doing so.

If the record has not yet been filed, then on behalf of appellant or appellant’s representative, counsel would file a written abandonment in the superior court. Filing an abandonment of appeal operates as dismissal of it. (Conservatorship of Oliver (1961) 192 Cal.App.2d 832, 836.)

If the record on appeal has already been filed, the appellant’s representative must file a written request for dismissal in the appellate court. The appellate court has discretion as to whether to dismiss or not dismiss an appeal when a request or stipulation for dismissal has been filed with that court after the filing of the record.

Under either scenario, Code of Civil Procedure, section 913, provides the effect of dismissing the appeal: “The dismissal of an appeal shall be with prejudice to the right to file another appeal within the time permitted, unless the dismissal is expressly made without prejudice to another appeal.” Keep in mind that a dismissal with prejudice affirms the judgment or appealable order, and therefore has res judicata implications as well as implications for who is the “prevailing party” for purposes of obtaining costs. (See Estate of Sapp (2019) 36 Cal.App.5th 86, 100; Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.278(a)(2); Unnamed Physician v. Board of Trustees (2001) 93 Cal.App.4th 607, 612.)

Settlement procedure and a cautionary tale

Lengthy appellate litigation and risk of reversal can highlight for parties the advantages of reaching a settlement, even at such a late stage. It is not uncommon for a prevailing party to attempt to reach finality by offering to waive recovery of costs in exchange for the waiver of an appeal, saving both parties money that would otherwise have been spent on what may appear to be a gamble.

Another common timeline for settlement on appeal is after the notice of appeal has been filed and prior to briefing, at which time the court may order the parties to mediation. Not every case is ordered to mediation, but mediation offers a preview into what the appellant believes warrants reversal and how persuasive the argument may be to an impartial decision-maker.

Less frequent, but still common, is settlement after some or all of the briefing has been filed. This could be the result of some really stellar brief writing, or may be attributed to new law being enacted or other circumstances that moot the appeal or undermine the appellate arguments supporting reversal or affirmance.

Rarely, but not unheard of, the parties will settle just before or after oral argument. I spoke with a long-time appellate specialist who told me that he was notified by trial counsel of an agreement to settle as he was literally walking into court for the argument!

A cautionary tale for those who attempt to settle at the “last minute” of the appeal. Did you know that sometimes, even if the parties decide to settle the case, the appellate court will not accept the dismissal and will instead issue its opinion anyway? An appellate court has “inherent power to retain a matter, even though it has been settled and is technically moot, where the issues are important and of continuing interest.” (Burch v. George (1994) 7 Cal.4th 246, 253, fn. 4; see also Cadence Design Systems, Inc. v. Avant! Corp. (2002) 29 Cal.4th 215, 218, fn. 2 [after settlement, court may exercise discretion and “issue an opinion ‘to resolve the legal issues raised, which are of continuing public interest and are likely to recur’”].)

In Kinda v. Carpenter (2016) 247 Cal.App.4th 1268,1271, fn. 1, the parties filed a notice of settlement in the Court of Appeal two weeks after oral argument in the case. The Sixth District concluded dismissal of the action at this extraordinarily late stage of the proceedings based on settlement or stipulation of the parties is discretionary rather than mandatory, and refused to dismiss the appeal. Kinda relied on Bay Guardian Co. v. New Times Media LLC (2010) 187 Cal.App.4th 438, 445, fn. 2, another case in which the parties unsuccessfully attempted to settle and dismiss the case after oral argument and submission of the case.

What obligations does an attorney have to notify the appellate court of the pending settlement talks? The answers hinge on timing and the counsel should become acquainted with rule 8.244 of the California Rules of Court.

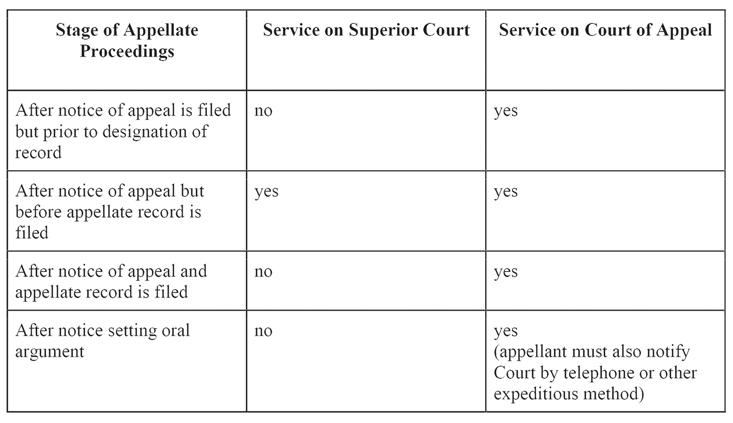

After a notice of appeal has been filed, if the case settles either as a whole or as to any party, the appellant who has settled must immediately serve and file a notice of settlement in the Court of Appeal. (Judicial Council form CM-200 suffices.) If the parties have designated a clerk’s or a reporter’s transcript and the record has not yet been filed in the Court of Appeal, the appellant must also immediately serve a copy of the notice on the superior court clerk. (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.244(a)(1).) If the case settles after the appellant receives a notice setting oral argument, the appellant must also immediately notify the Court of Appeal by telephone or “other expeditious method.” (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.244(a)(2).)

The notice of settlement may be unconditional or conditional. If it is unconditional, the appellant who filed the notice of settlement must, within 45 days of filing the notice, file either an abandonment (if the appellate record has not yet been filed), or a request to dismiss (if the appellate record has already been filed). (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.244(a)(3).) If the notice of settlement is conditional, the notice of abandonment or dismissal (depending on whether the record has been filed) must be filed within 45 days of the satisfaction of the condition. If the appellant fails to file the dismissal or abandonment notice in a timely manner, or a letter stating good cause why the appeal should not be dismissed within the time period provided by the rules, the court may dismiss the appeal as to that appellant. (Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.244(a)(4).) However, if the court dismisses the appeal, it may order each side to bear its own costs on appeal.

Deceased client

Appeals are notoriously slow, so it may not come as a huge surprise that pending resolution of the case, sometimes a client dies. When that occurs, what steps does the attorney need to take? Does the appeal continue? Is the attorney required to notify the court?

What steps an attorney must take depends on when in the proceedings the client has passed away. Typically, counsel should advise the court that the client has died and request a stay pending appointment of a personal representative to continue the appeal. However, when the case has already been submitted on the briefs, or argument has been held and the only step remaining is for the court to issue its opinion, then no stay of proceedings is necessary.

Terminal illness, economic hardship, and calendar preference

Not every client has unlimited time to wait for the resolution of their case on appeal. According to the Judicial Council of California’s 2023 Court Statistics Report, for civil appeals in the fiscal year 2021-2022 (the most current data), the statewide median time from the notice of appeal to the opinion is 569 days. Put differently, that means that half of the appeals are decided in less than (approximately) 18 months and half take longer than that. Ninety percent of appeals are decided statewide within 975 days. Different appellate districts take longer. For example, the median time for the Sixth District (San Jose) is 920 days as opposed to the statewide median of 569 days. At the other extreme, Division 6 of the Second Appellate District (Ventura)’s median time is 418 days.

Against such a protracted time frame, California’s legislature has concluded that certain categories of cases and litigants require expedited procedures. These include, for example, Code of Civil Procedure section 44 probate proceedings, contested elections, libel by public official (Code Civ. Proc., § 44), and judgment freeing minor from parental custody (Code Civ. Proc., § 45). Appellate courts should exercise their discretion to grant preference when a statute provides for trial preference, even if the statute does not explicitly apply to appellate proceedings. (See Warren v. Schecter (1997) 57 Cal.App.4th 1189, 1198-1199.) Examples include certain election matters (Code Civ. Proc., § 35), and more commonly, a party over 70 and in poor health, a party with terminal illness, or a minor in a wrongful death action (Code Civ. Proc., § 36).

When a party becomes terminally ill or a party over 70 years old suffers a significant decline in his or her health during the appeal, and therefore needs an expedited appeal, the California Rules of Court, rule 8.240, requires the party to “promptly” file a motion for calendar preference, i.e., as soon as the ground for preference arises. Expediting such procedures is necessary for litigants facing certain circumstances because “justice delayed is justice denied.” (Warren, supra, 57 Cal.App.4th at 1199, quoting Laborers’ Internat. Union of North America v. El Dorado Landscape Co. (1989) 208 Cal.App.3d 993, 1007.)

When circumstances arise (such as economic hardship) that do not fall within any statutory provision entitling the litigant to calendar preference, but which nevertheless may warrant expedited scheduling, the appellate court may exercise its discretion to grant calendar preference. (See Advisory Committee Comment to California Rules of Court, rule 8.240.)

What does it mean to receive calendar preference? Normal flexibility in the briefing schedule, including liberally extending time to file the briefs, may be curtailed in a case receiving calendar preference. Similarly, cases receiving calendar preference may receive priority when scheduling oral argument.

New evidence

“If it’s not in the record, it doesn’t exist for purposes of the appeal.” This common refrain of appellate attorneys is true – usually. One extremely limited exception to this rule is the writ of coram vobis (the appellate corollary to the slightly better-known writ of coram nobis that is filed in the trial court.) The writ is an appellate court order directing a trial court to reconsider its judgment, in light of new evidence that is not in the trial record. The writ is commonly used in criminal appeals, but the same principles apply to civil appeals.

Before getting too excited, there are extremely stringent criteria for entitlement to such a powerful writ. (1) Certain evidence exists that was not presented to the trial court; (2) The failure to present this evidence was not due to negligence on the petitioner’s part; (3) If the evidence had been presented, the outcome of the trial would have been different; (4) The new evidence must not relate to issues already tried. Issues of fact, even if they are incorrectly adjudicated, can only be reopened on a motion for new trial. This rule applies even if the evidence isn’t discovered until after the time to move for a new trial has expired; (5) Due diligence could not have uncovered this evidence earlier. The petitioner should be able to demonstrate the time and circumstances under which the evidence was discovered. The appellate court must then determine whether the petitioner should have found this evidence earlier, using all due diligence; (6) The writ cannot be used if the petitioner failed to motion for a new trial or appeal. Other viable legal remedies, therefore, must have already been exhausted. Failure to take these steps would render the writ of coram vobis unavailable.

Some courts have gone even further to limit the writ, for example, by requiring proof of extrinsic fraud. Examples may include intentional misrepresentation or nondisclosure of evidence that effectively prevented a fair presentation of relevant facts at trial. Regardless, and in light of the above requirements, this writ is only to be used in rather extraordinary circumstances.

Global pandemic and other emergencies

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, California courts had provisions for emergency tolling and extensions of time in the event of public emergency (such as earthquake, fire, public health crisis, or other public emergency, or by the destruction of or danger to a building housing a reviewing court). California Rules of Court, rule 8.66, provides under such emergencies that the Chair of the Judicial Council may toll deadlines imposed by the rules for up to 30 days (renewable for additional periods not to exceed 30 days per renewal). The Advisory Committee Comment notes that the tolling and extension of time authorized under this rule include and apply to all rules of court that govern finality in both the Supreme Court and the Courts of Appeal.

As with the Superior Courts of the State, the COVID-19 pandemic threw all of the state appellate courts for a loop. Deadlines were tolled via emergency orders, and oral arguments (when they resumed) were handled remotely. As of November 2023, most of the courts have returned to in-person oral argument, but virtual appearances have become common alternatives, especially when accommodating health concerns.

Parting ways

Every so often, for a variety of reasons, clients and their attorneys part ways during the appeal. Regardless of the reason, there are limitations on whether the attorney may unilaterally withdraw from the representation and under what circumstances he or she may do so.

Substituting attorneys is typically straightforward. However, withdrawing as an attorney (resulting in the party continuing the appeal in pro per) requires a motion. California Rules of Court, rule 8.36 provides the procedure for doing so. When the substitution or withdrawal occurs after the notice of appeal has been filed, the substitution of attorney must be effected by order of the appellate court. (Echlin v. Superior Court of San Mateo County (1939), 13 Cal.2d 368, 374.)

Notably, not all litigants may proceed in pro per. In most cases, a guardian ad litem, unincorporated association, corporation, personal representative, probate fiduciary, trustee, conservator, or guardian, may not represent their own interests and instead, must substitute an attorney.

Where the attorney’s withdrawal will leave the party in pro per, the withdrawing attorney must ensure that the withdrawal will not harm the client. For instance, if the attorney attempts to withdraw representation a week prior to the oral argument in the case, the reviewing court may properly deny the motion to withdraw, noting the likely prejudice to the party based on such timing and difficulties in finding alternative counsel or preparing to proceed without counsel.

Conclusion

Ample opportunities abound for a variety of surprises and plot twists during the lengthy duration between filing the notice of appeal and the court’s decision. This is part of the fun of practicing law. Practically speaking, however, take a deep breath and do not panic. Consult the Rules of Court and your colleagues when the unexpected arises, and when all else fails, enjoy charting unknown waters.

Janet R. Gusdorff

Janet Gusdorff is a California Certified Appellate Law Specialist and the founder of Gusdorff Law, P.C. She represents plaintiffs in complex, high-stakes civil appeals and partners with trial lawyers to navigate post-trial strategy, preserve issues, and elevate written advocacy. She can be reached at janet@gusdorfflaw.com.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine