Jumping into the world of skydiving

Accidents and mishaps that occur during transportation of skydivers to jump is a unique and interesting area of law

While some people hesitate to even board an aircraft, skydivers leap out of aircraft, thousands of feet above ground level, nearly four-million times across the United States in 2022. (Lopez, A., Skydiving Centers in U.S. States 2023 (May 14, 2024) Statista <https://www.statista.com/statistics/1084537/skydiving- centers-us-states> [as of March 13, 2025].) As of October 2023, there were 21 skydiving centers in the State of California, the most of any state in the country. Across the nation, over 300 centers and clubs for skydiving exist, operating over 500 skydiving aircraft. (Fed. Aviation Admin., Flying for Skydive Operations (September 2016) publ. no. P-8740-62 (hereinafter FAA Publ. P8740-62).) To make those dives, an aircraft must be skillfully and carefully operated to transport pilots and jumpers. But what happens when something goes wrong? This article is intended to assist you in analyzing and handling a skydiving-related case.

What is skydiving? Skydiving is the act of jumping from an aircraft and using a parachute to slow descent and assist in landing. Andre-Jacques Garnerin is credited with the first parachute jump in 1797, which he did from a hot-air ballon. Over 100 years later, in 1912, U.S. Army Captain Albert Berry performed the first parachute jump from an airplane. (Discovery UK, What is Skydiving? (August 5, 2022) Discovery Networks International <https://www.discoveryuk.com/adventure/what-is-skydiving> [as of March 13, 2025].)

Today, skydiving is an extreme sport participated in by adults widely ranging in age. Skydiving provides jumpers the thrill of a freefall at speeds reaching up to 130 miles per hour before deploying a parachute. In the United States, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) regulates the sport and has minimum standards for instructors and operators. The FAA also ensures compliance of these standards by inspecting facilities. (FAA Publ. P8740-62, supra.) Several skydiving organizations exist, such as the United States Parachute Association (USPA). These organizations assist in providing safety guidelines, training programs, and licensing procedures. (Fed. Aviation Admin., Advisory Circular 105-2E (December 4, 2013) p. 2 (hereinafter AC 105-2E).)

General overview

Skydivers typically jump from altitudes of 7,500 feet up to 15,000 feet – nearly three miles above the surface of the earth. (Turoff, supra.) Under USPA guidelines, skydivers must be at least 18 years old and there is generally no upper limit on age. (Skydivers Instruction Manual (2025) United States Parachute Association <https://www.uspa.org/SIM/2#top> [as of March 14, 2025] (hereinafter SIM).) As many know, former President George Herbert Walker Bush loved to skydive and did so up until he turned 90 years old. (Porter, T., George HW Bush would have been 95 today. He used to celebrate every fifth birthday by going skydiving (June 12, 2019) Business Insider <https://www.businessinsider.com/george-hw-bush-marked-birthday-with-skydive-2019-6> [as of March 14, 2025].) There are other requirements for skydiving, however, including for students, instructors, pilots, and parachute equipment, as well as for the operation, maintenance, and inspection of the aircraft used. (FAA Publ. P8740-62, supra.)

Although an exhilarating sport, there are numerous and unique challenges that arise when accidents occur.

How safe are skydiving operations?

You may have overheard someone say, “Why would anyone jump out of a perfectly good aircraft?” Statements like that make two huge assumptions – that skydiving aircraft are perfectly good aircraft and that the aircraft is operated by a perfectly good pilot.

In 2008, the NTSB investigated the safety of parachute-jumping operations. The findings included the following issues: inadequate aircraft maintenance and inspections; pilots deficient in the performance of basic airmanship tasks, including weight and balance calculations, preflight inspections, and especially emergency and recovery procedures; that 14 C.F.R. Part 91 insufficiently ensures pilot proficiency in specific aircraft and does not address the unique qualities of skydiving flights. Additionally, the NTSB concluded that FAA surveillance and oversight of parachute operators was inadequate to ensure proper aircraft maintenance and safe operations. (Natl Trans. Safety Bd., Special Investigation Report on the Safety of Parachute Jump Operations (September 16, 2008) NTSB/SIR-08/01 (hereinafter “NTSB SIR801”).) All these factors should be carefully evaluated in any case being reviewed by an attorney.

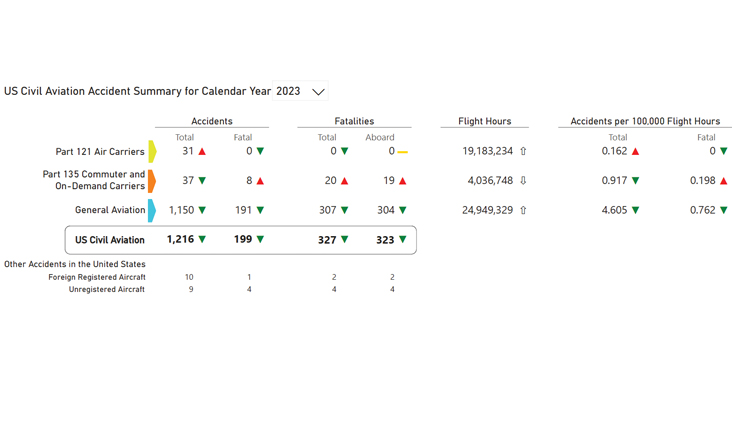

The NTSB makes available on its Web site the civil aviation accident summary. (Natl. Trans. Safety Bd., U.S. Civil Aviation Summary (2023) <https://www.ntsb.gov/safety/StatisticalReviews/Pages/CivilAviationDashboard.aspx> [as of March 14, 2025].) For 2023, the chart shows (see below):

The chart reflects that, for 2023, “general aviation” aircraft, which includes skydiving aircraft, had an accident rate (per 100,000 flight hours) of five times that of commuter and on-demand carriers, and 28 times that of air carriers. That is not to say that the accident rate for aircraft involved in skydiving operations is as high as other general aviation. But it does tend to show that pilots and aircraft operating under 14 C.F.R. Parts 121 and 135, are involved in far fewer accidents and fatalities per flight hour than those operating under other parts of the aviation regulations.

Skydiving is often associated with the hiring and employment of commercial pilots with low-flight-hours and aircraft that are poorly maintained and pushed to their limits for increased revenue. (See NTSB SIR801.) This commercial activity does not require an air operator certificate under 14 C.F.R. § 119.1(e)(6), and operates under 14 C.F.R. Part 91, not having to follow the more stringent requirements and rules of Part 135. This means there are no “minimum hours” for pilots as long they hold a commercial certificate. (14 C.F.R. §§ 61.129, 61.133 (2024); U.S. Civil Aviation Summary, supra.)

Understanding the legal framework

To properly evaluate a skydiving case, you must understand the law and rules that govern it.

Federal Aviation regulations

Federal Aviation Regulations (unofficially, “FARs”) are rules that govern aviation in the United States. FARs appear in Title 14 of the Code of Federal Regulations. The U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is responsible for regulating the usage of airspace in the United States and create and enforce the FARs. (U.S. Parachute Assn., Skydivers Instruction Manual (2025) § 9 (summarizing applicable FARs) <https://www.uspa.org/SIM/9> [as of March 14, 2025].) For skydiving, the FAA fulfills its responsibility by regulating certain aspects of skydiving. (Ibid.) The industry relies heavily on self-regulation by its participants as well as through the recommendations and guidelines of the USPA. (Ibid.)

First and foremost, the FAA’s role is to provide for the safety of air traffic, as well as persons and property on the ground. The FAA does this by ensuring that pilots, air traffic controllers, mechanics, and parachute riggers are certified. There are also requirements related to the aircraft and parachutes of jumpers. For failures and violations, the FAA can suspend certificates and even revoke them as well as imposing fines.

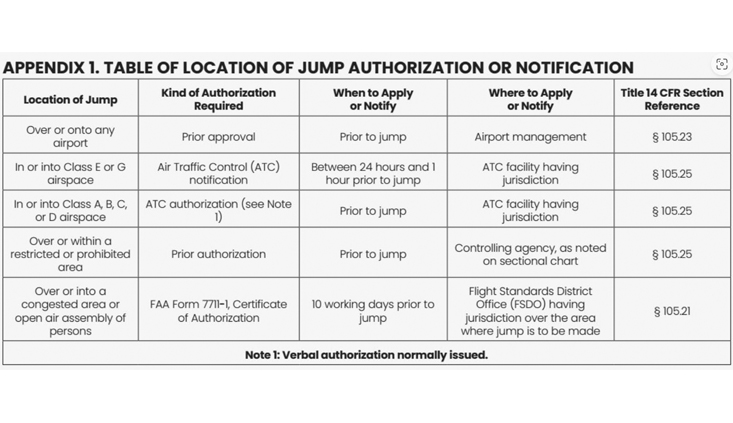

Some of the key FARS governing skydiving are: FAR Part 61, which governs the certification of pilots; FAR Part 65, which governs parachute riggers; FAR Part 91, which covers general flight rules pertaining to skydiving operations; FAR Part 105, which covers generally skydiving; and FAR Part 119, discussing the limits of jump flights. There are also Advisory Circulars (AC) which provide details and assistance regarding various important issues such as AC 90-66B which provides Recommended Standard Traffic Patterns and Practices for Aeronautical Operations at Airports without Operating Control Towers; AC-90-66, which provides information for multi-users at uncontrolled airports and AC 105-2E, which provides suggestions on how to improve sport parachuting. There are also FAA Air Traffic Bulletins which provide information for air traffic controllers. This is a very regulated sport/activity. As an example, see Appendix 1 (on this page) showing the Table of Location of Jump Authorization or Notification.

(AC 105-2E, supra.)

Because of the challenging nature of skydiving, the USPA and FAA have put together pamphlets and materials with some of the most critical information. In Federal Aviation Administration, Flying for Skydive Operations (September 2016) publ. no. P-8740-62, the FAA and USPA discuss some of the most important issues in skydiving including:

Based on FAA standards almost all skydiving flights are considered commercial operations because there is compensation for the flight.

If the aircraft is used in a commercial operation, the aircraft is subject to an annual inspection and a 100-hour inspection.

Pilots must hold a commercial pilot certificate, as well as current medical certificate (despite that, exemptions exist for flights operating within 25 miles of a departure airport).

Liability and negligence

The great thing about these regulations, advisory circulars and other recommendations are that they truly assist us as lawyers in understanding the rules that govern. Without knowing the rules, it’s hard to determine if one was broken or if someone breached a duty. When a skydiving injury or accident comes to you for evaluation, you can start there.

What is the duty?

Of critical importance to practitioners is, what duty applies? Is it the heightened duty of care owed by a common carrier for reward? CACI 902 supplies the law regarding the duty of a common carrier and its Sources and Authority are instructive:

The Civil Code treats common carriers differently depending on whether they act gratuitously or for reward. ‘A carrier of persons without reward must use ordinary care and diligence for their safe carriage.’ But ‘[c]arriers of persons for reward have long been subject to a heightened duty of care.’ Such carriers ‘must use the utmost care and diligence for [passengers’] safe carriage, must provide everything necessary for that purpose, and must exercise to that end a reasonable degree of skill.’ While these carriers are not insurers of their passengers’ safety, ‘[t]his standard of care requires common carriers ‘to do all that human care, vigilance, and foresight reasonably can do under the circumstances.

(Huang v. The Bicycle Casino, Inc. (2016) 4 Cal.App.5th 329, 338 [208 Cal.Rptr.3d 591], internal citations omitted.) (CACI No. 902, Sources and Authority (Nov. 2024) (all further citations to CACI are to Nov. 2024 ed.).)

Or, does the assumption-of-risk doctrine apply, meaning that there is no duty of ordinary care to protect participants from risks inherent in certain activities, like skydiving? If there was a waiver signed by the participants, then there is likely an express assumption-of-the risk defense. However, “[e]xpress assumption of risk does not relieve the defendant of liability if there was gross negligence or willful injury.” (Civ. Code, § 1668.) But the primary assumption-of-risk doctrine will likely become relevant due to the inherently dangerous nature of skydiving. (Rosencrans v. Dover Images, Ltd. (2011) 192 Cal.App.4th 1072, 1081.)

Even if there are assumption-of-risk defenses, a plaintiff may be able to overcome those defenses if there was intentional or reckless conduct which was entirely outside the range of the ordinary conduct of the sport/activity, this conduct was a substantial factor in causing the harm, and the conduct increased the risks to plaintiff over those inherent in the sport/activity and the intentional/reckless conduct can be prohibited without fundamentally changing the activity or discouraging vigorous participation. (CACI No. 470.)

Additionally, CACI 472 provides another exception to the primary assumption-of-risk defense against owners, operators and event sponsors if there was an unreasonable increase in the risk or the owner, operator or event sponsor unreasonably failed to minimize a risk not inherent in the sport/activity. (CACI 472; Hass v. Rhody Co Productions (2018) 26 Cal.App.5th 11, 38 [duty exists to minimize risks extrinsic to the sport’s nature, if they can be addressed without altering the activity’s essential nature].)

The duty of care must be analyzed for each entity involved in the event/activity, including the pilot, co-pilot (if applicable), skydiving instructor and operator, as well as owner and event sponsor (if any).

Investigating the incident

As with all accidents, investigation of the accident scene and products involved is critical. Gathering the evidence in terms of aircraft, aircraft parts, logbooks, witness statements, and physical evidence, and ensuring the evidence is preserved is paramount. In an aviation accident, there may be reports from both the FAA and National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) to assist with an understanding of the incident. Reports of local agencies, such as police and firefighters may also be available.

These full NTSB and FAA reports may take time to complete (although preliminary reports with very few details may be available within days of the incident). Furthermore, an ongoing investigation may prevent access to the plane, components of the plane, as well as certain information you might need in your case. If a government entity or public entity is involved, you may need to comply with government claims deadlines earlier than these reports are ready and you may need to rely on information available by way of news media, social media or other online forums. For example, Pilots of America has a website where there is a forum regarding Aviation Mishaps (www.pilotsofamerica.com/community/forums/aviation-mishaps-59). ProPilotWorld.com has a similar forum (www.forums.propilotworld.com/forumdisplay.php?124-Aviation-Accidents-Investigations).

Depending on who is assigned to investigate on behalf of the FAA and NTSB, you may be able to speak with the lead investigator to get some information regarding the status of the investigation, location of evidence, and estimates of report completion. However, many investigators will simply refer attorneys to general counsel for the FAA or NTSB. The FAA provides information on its website including summaries of recent accidents and also gives instructions regarding commercial and general aviation matters. (Fed. Aviation Admin., FAA Statements on Aviation Accidents and Incidents <https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/statements/accident_incidents> [as of March 14, 2025].) The FAA’s website instructs:

For General Aviation:

Contact local authorities for the names and medical conditions of anyone on board.

A preliminary FAA report will be posted, usually on the next business day. [http://www.asias.faa.gov.]

If known, the aircraft registration number (N-number) can be searched at the Aircraft Registry. [http://registry.faa.gov/ aircraftinquiry/Search/NNumberInquiry.]

If the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) is also investigating, it will provide all updates.

For Commercial Aviation:

Contact the airline for information about passengers and crew, flights and schedules.

If the National Transportation Safety Board is also investigating, it will provide all updates.

The NTSB’s website provides a search function to look up information on an incident. (Natl. Trans. Safety Bd., Aviation Accident Search <https://www.ntsb.gov/Pages/AviationQueryv2.aspx> [as of March 15, 2025].) This is where you will find the preliminary report and, eventually, the final report for an incident. After the NTSB completes its investigation and posts the final report, it also posts the docket – which includes the investigation materials used by the NTSB in completing the report. This often includes witness statements, pertinent medical information, computations, toxicology reports, photographs, and pertinent factual reports. However, even the preliminary report often includes helpful information, including pictures and details that can be used in evaluation and prosecution of a civil case.

Once the final reports of the FAA/NTSB are complete, the findings and recommendations on the FAA and NTSB might be useful in your case and to assist you in developing your theories. However, the report likely will not be admissible in your case. Additionally, you will likely not be able to depose, interview, or discuss the findings and recommendations with these officials. The Federal Aviation Act of 1958 itself specifically prohibits anything other than factual evidence from the NTSB and/or FAA investigation from being admitted in civil litigation, and definitely not any probable cause, conclusions/opinions, findings and recommendations of the reports. (Federal Aviation Act of 1958, § 701(e), 49 U.S.C. § 1154(b).) However, the factual portions of the NTSB and/or FAA reports may be admissible, depending on the jurisdiction. In fact, the NTSB provides an internet link within the final report that automatically generates a “factual report,” which the NTSB states may be admissible under 49 U.S.C. § 1154(b).

Experts’ roles in a skydiving case

Experts are a critical part of your case in determining if there is liability in a potential skydiving case. Experts will be needed in accident reconstruction, to evaluate the airplane as a product itself, the conduct of the pilot in operation of the aircraft, whether maintenance personnel performed well and to determine whether maintenance and repairs were timely done, to evaluate the businesses who might be operating the aircraft for use in the skydiving enterprise, as well as component part suppliers and manufacturers.

Although you may not have access to the aircraft and its components for a while, depending upon when the NTSB and FAA have completed any investigation or decide to release the aircraft prior to finalizing their report(s), you should still be able to access information regarding the plane to begin researching potential defects.

One way to do this is to check the FAA website’s Airworthiness Directives. The FAA describes its Airworthiness Directives as: “legally enforceable regulations issued by the FAA in accordance with 14 CFR part 39 to correct an unsafe condition in a product. Part 39 defines a product as an aircraft, engine, propeller, or appliance.” (Fed. Aviation Admin., Airworthiness Directives <https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/airworthiness_directives> [as of March 15, 2025].) These directives include everything from tail rotor blades to the main rotor head and everything in between. They provide useful guidance regarding your aircraft and potential defects which may have been a factor in the mishap you are investigating. Multiple experts will likely be needed in any skydiving incident to evaluate the different types of liability that you will have to consider.

Pilot and operator liability

Often, the findings and conclusions of the FAA and NTSB will be that the cause of the accident was “pilot error.” You will need to determine whether the pilot followed all safety protocols, was in adequate health with proper medical certificates, maintained proper logbooks, kept the aircraft properly maintained and repaired, and followed proper protocol and procedure with regard to transporting passengers and equipment in a skydiving operation. Piloting for a skydiving operation requires a tremendous amount of skill and knowledge.

Often, the pilots are taking multiple passengers, jumpers and customers quickly up to jump and then “race to the ground” to pick up more customers and do it again and again. Although the pilot in command is ultimately responsible for the flight, the pressure of the skydiving operation should be taken into consideration. Often, these skydiving pilots are pressured to take equipment that is overused, not properly maintained, and beyond its safe limits. Sometimes, pilots will fly with low fuel to reduce weight, in order to climb faster and take off easier. Occasionally, warning lights, alarms, and gauges stop working, yet pilots will fly, knowing they no longer operate properly. Numbers and profits are put first and safety second. This is when the problems arise.

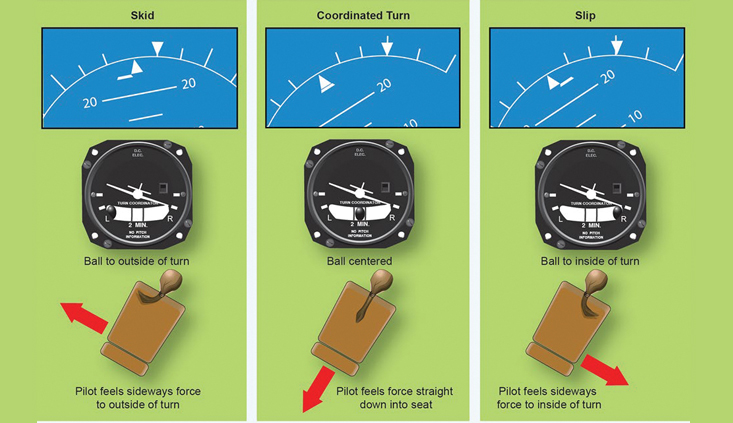

An example of pilot error that can occur in operating a skydiving aircraft involves “unporting,” where fuel in the aircraft fuel tanks flows away from fuel pickup points that supply the engine due to steep attitudes, hard maneuvers, or “uncoordinated turns,” with low fuel. (Namowitz, D., Training Tip: ‘Unported’ Fuel (December 27, 2013) Aircraft Owners and Pilots Assn. (AOPA) <https://www.aopa.org/news-and-media/all-news/2013/december/27/training-tip-unported-fuel> [as of March 15, 2025].) This can occur even though the fuel level may be within the safe operating range recommended by the manufacturer, due to the aircraft being flown in a manner outside of the normal range of operation. “Uncoordinated flight” simply means that the fuselage is not directly lined up with the direction of travel. In level flight, it can easily be corrected with the rudder. However, “uncoordinated turning” refers to a condition where the ailerons are not ‘coordinated’ with the rudder during a turn, resulting in an imbalance between the centrifugal force and gravity.

This can result in the aircraft either slipping toward the inside of the turn or skidding toward the outside of the turn. (Fed. Aviation Admin., Airplane Flying Handbook (2021) pp. 3-11 to 3-13, publ. no. FAA-H-8083-3C.) See graphic on page 123.

The imbalance affects the fuel in the tanks in much the same way, which can lead to unporting and to fuel starvation to the engine and loss of power. Unporting is frequently scrutinized as an accident cause when an aircraft engine fails with some fuel remaining, and when no mechanical damage is found.

Skydiving-company liability and responsibility

Skydiving companies must ensure that their equipment is well maintained, their pilots are well trained and they do not “push” the pilot and the equipment to the limits to get as many jumpers as possible in the least amount of time. Skydiving companies are responsible for their aircraft and their equipment, including parachutes, harnesses and other equipment utilized in the operation. Safety protocols and training of the employees and personnel of the skydiving company will be an important part of the investigation to determine if there is liability. One thing to review is whether guidelines and recommendations of the United States Parachute Association (USPA) were followed, especially with regard to safety checks, briefing, training, equipment, emergency procedures, weather, and other aircraft. (Skydivers Information Manual (2025) United States Parachute Association <https://www.uspa.org/SIM/5 [as of March 14, 2025].). There are plenty of safety recommendations, guidelines and best practices that would prevent mishaps if these recommendations and guidelines are followed.

Products liability

There are various products that are used and relied upon in ensuring skydiving is safe. First, the aircraft itself. Second, the component parts of the aircraft. Third, the equipment used in skydiving, including parachutes and harnesses. All these products could cause a mishap. But, for purposes of transportation cases, the most important product to review is the aircraft. Often, these skyjumping operations are performed using Cessnas or other similar aircraft. A careful review of the product must be done to determine the age of the product, whether there were defects in the engine of the aircraft, etc.

Important to consider is whether the 18-year statute of repose controls and will limit your ability to pursue a product-liability claim versus the manufacturer of the aircraft. General Aviation Revitalization Act of 1994 (GARA) is a federal law that imposes an 18-year statute of repose on claims against both manufacturers of general aviation aircraft and their component parts. Typically, this means that any claim or lawsuit arising from the aviation incident for general aviation aircraft must be brought, if at all, within 18 years of the time the aircraft and its parts were delivered to the original purchaser of the aircraft.

The exception(s) to the statute of repose under GARA are rather narrow. They include:

Withholding, concealing, or misrepresenting information from the FAA directly related to the cause of the accident;

Where the accident victim was in flight to obtain medical treatment (such as an air ambulance flight);

Where the person injured or killed was not aboard the aircraft (such as a person on the ground hit by an aircraft); and

Where a written warranty is the subject matter of the suit.

(General Aviation Revitalization Act of 1994, Pub. L. No. 103-298 (hereinafter GARA), § 2(b).)

A further exception exists where the manufacturer installs new parts, replacement parts, or performs a modification. However, this exception does not do away with the statute of repose, as with the exceptions above, rather, it resets the 18-year clock. (GARA § 2(a)(2).)

Conclusion

Transportation of skydivers, as well as accidents and mishaps that occur during transportation is a unique and interesting area of law. There are many avenues of recovery to investigate and several issues to consider when analyzing a potential case or navigating the liability in a case you have accepted and are pursuing. There is an incredible amount of learning that must be done to ensure that you are up to date on the law, rules, regulations, defenses and paths to recovery for those injured in a skydiving aviation incident. By understanding the applicable rules and laws, investigating the mishap/incident thoroughly, conducting a careful analysis of the potential liability, and ensuring regulatory compliance on the part of all those involved, you can successfully prosecute a case for a skydiving mishap.

Michelle M. West

Michelle Marie West is a partner with the law firm of Robinson Calcagnie in Newport Beach, California where she has practiced for 18 years. Her law practice is devoted to obtaining recovery for individuals who are catastrophically injured due to defective products, including vehicles, tires, skylights, machinery, medical devices, and pharmaceuticals. She also handles dangerous-condition cases, trucking cases, premises liability matters, sexual assault, and bullying cases on behalf of injured victims and survivors. Ms. West has been nominated as a Top 100 Southern California Superlawyer multiple times, Top 50 Orange County Superlawyer, and Top 50 Women Southern California Superlawyer, as well as being recognized by Best Lawyers. She is on the Board of the Los Angeles Trial Lawyers Charities, Past President of the Western Trial Lawyers Association and currently serves as President of the Orange County Trial Lawyers Charities.

In her free time‚ Ms. West enjoys weightlifting, traveling, marathons (completing over 100) as well as participating in ultra-distance running events, cycling events, and triathlons, and has completed over 10 full Ironman® triathlons. She competes in the Badwater Ultramarathon running event to raise money for charity and has finished the event five times.

Patrick Embrey

Patrick Embrey is a partner at Robinson Calcagnie, Inc., where he represents plaintiffs in large and complex personal injury cases. Mr. Embrey focuses on cases in the areas of product liability, road design, and commercial transportation accidents.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine