Med-pay lien claims

A look at the language in a med-pay contract and its interplay with the “common fund” and “made whole” doctrines

Lien reimbursement provisions contained in automobile policies are commonly referred to as “med-pay” liens. These liens are contractual provisions requiring reimbursements every client and attorney needs to be aware of. Liens are essentially lines of credit that must be reimbursed by the injured party. Attorney signatories to a valid lien contract owe a fiduciary duty to the lien claimant.

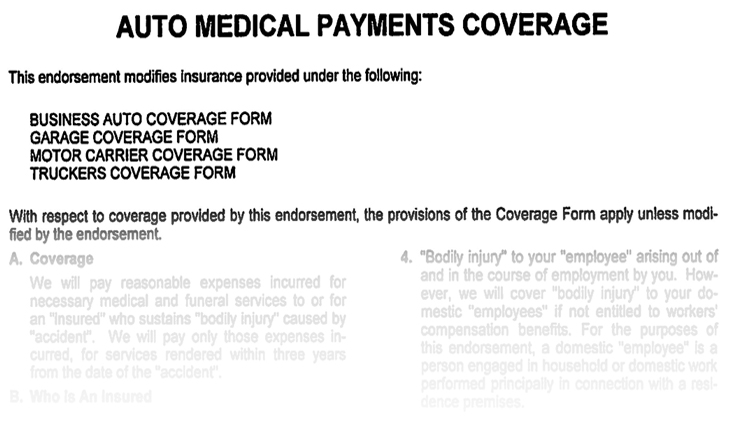

Med-pay contracts

Some automobile insurance contracts provide for medical coverage payments (med pay) for injuries sustained in a collision within the insured vehicle, in a non-insured vehicle, in a non-owned vehicle, or as a pedestrian. Each policy may vary as to the amount or limits of coverage, conditions for coverage and reimbursement requirements. The vast majority of med-pay policies require reimbursement where the insured obtains monetary recovery from a third party.

Policy language

Language in an insurance policy can be deceiving, so ensure you read it in its entirety. For example, a provision allowing for “subrogation” without the requirement of allowing interpleading into litigation is just a lien on a claim. (Lee v. State Farm Mut. Auto Ins. Co., (1976) 57 Cal.App.3d 458, 466-469.) “Reimbursement” provisions are essentially lien claims, and only need to be paid if there is recovery.

“Subrogation” is the term used when a health care provider is given the right to directly sue the third-party tortfeasor. The term also applies to an automobile carrier’s rights to recovery for payment of its insured’s vehicle damage. The difference between the terms “lien,” “subrogation” and “reimbursement” were thoroughly discussed in 21st Century Ins. Co. v. Superior Court (Quintana) (2009) 47 Cal.4th 511.

Without statutory authority, an insurance company or health care provider providing medical benefits cannot require an assignment of benefits or be subrogated into the matter. (See Block v. Cal. Physicians’ Services (1966) 244 Cal.App.2d 266.) Statutes that allow for subrogation against the third-party tortfeasor are Civil Code section 3045.1 et. seq., regarding statutory hospital liens; Labor Code section 3856, for workers compensation benefit reimbursements; Government Code section 23004.1 for services provided at a county facility; and Government Code section 13963 for victims of violent crime.

Automobile med-pay repayment provisions

A med-pay provision in an automobile insurance policy is strictly contractual. No statutes mandate such provision. Additionally, there is no statute requiring reimbursement or allowing for a subrogation right of action to the carrier. Thus, an insurance carrier seeking reimbursement must have such right set forth in the insurance contract. (See Progressive West Ins. Co. v. Superior (2005) 135 Cal.App.4th 263, 272.)

Unless the policy requires reimbursement, none is required. Thus, some automobile med-pay provisions require full reimbursement from a recovery against a third-party tortfeasor, some will only pay medical bills if other insurance is exhausted, and some do not have any conditions to the payment of the medical bills other than the submission of medical bills within a certain time period. The latter effectively allows for double recovery of the medical bill value.

There is long-standing case law that allows for attorney fees and proportional litigation costs to be deducted from the lien repayment. These deductions are allowed under the “Common Fund Doctrine” (discussed in depth below), requiring the pro rata sharing of fees and expenses. To hold otherwise would unjustly enrich the insurance company with free legal services in recovering the lien claim. (See Lee v. State Farm Mutual Ins., Co. (1976) 57 Cal.App.3d 458, 466-469.)

The med-pay insurer need not make medical payments. After the insured settles with the third-party tortfeasor, the med-pay insurer need not make medical payments. (See West v. St. Farm Mut. Auto Ins. Co. (1973) 30 Cal.App.3d 562.)

Injured passengers in insured vehicles with med pay

A non-owner automobile passenger who suffers injury in a vehicle with med-pay coverage is a third-party beneficiary under the insurance contract. The passenger is obligated to repay the automobile insurance carrier for those medical payments, so long as the insurance contract requires repayment. The passenger receives the benefits of the contract and is to pay the detriment required under the contract. (See Mercury Casualty Company v. Sharia Rae Maloney (2003) 113 Cal.App.4th 799.)

Common fund doctrine

As stated above, there is long-standing case law that allows attorney fees and proportional litigation costs to be deducted from the lien repayment. These deductions are allowed under the common fund doctrine, requiring the pro rata sharing of fees and expenses. To hold otherwise would unjustly enrich the insurance company with free legal services in recovering the lien claim. (See Lee v. State Farm Mutual Ins., Co. (1976) 57 Cal.App.3d 458, 466-469.)

The U.S. Supreme Court has recognized the common fund doctrine in the following way: “To allow ‘others to obtain full benefit from the plaintiff’s efforts without contributing … to the litigation expenses,’ we have often noted, ‘would be to enrich the others unjustly at the plaintiff’s expense.’” (US Airways, Inc., McCutchen (2013) 133 S.Ct. 1537, 1547.) In other words, the party with the lien that seeks reimbursement is to reduce its claim by its pro rata share of reasonable attorney fees and court costs necessary to prosecute the injured party’s claim against a third-party tortfeasor.

In a Kaiser lien case, Samura v. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc. (1993) 17 Cal.App.4th 1284, 1297, the court defined the common fund doctrine in the following manner: “It is well established that, when two or more parties are entitled in common to a fund created by a recovery from a third party, and the costs of litigation have been borne by only one of then, the courts in the exercise of their inherent equitable powers will require the apportionment of costs and attorney’s fees.” (Citing Lee v. State Farm Mut. Auto, Ins. Co., supra, 57 Cal.App.3d 458, 466-468.) Thus, the courts will reduce a health plan’s lien under the third-party liability provision by its pro rata share of the member’s costs in securing a judgment or settlement from the third party.

Note that although Samura defined the common fund doctrine, it was not applied as a holding in that matter. The doctrine, however, has been codified in Civil Code section 3040, and it has application to Kaiser lien claims (see below).

21st Century Insurance Company v. Superior Court (Quintana) (2009) 47 Cal.4th 511, 515 “requires pro rata sharing of an insured’s litigation costs as a condition of reimbursement” for recovery against a third-party tortfeasor. Quintana held that the insured’s attorney’s fees are “subject to a separate equitable apportionment rule…” The Court went on to explain that the rule, “requires the insurer to account for its fair share of the attorney fees by reducing the amount of reimbursement to cover some portion of those fees.” (Id. at 527. Also, see discussion in Chong v. State Farm Insurance (2010) WL 2175842.)

The common fund doctrine has no application when dealing with medical facilities providing charitable medical benefits under Government Code section 23004.1. That code provides the medical facilities a “first lien.” Such first-lien rights, however, are limited to judgments only. (Lindsey v. County of Los Angeles (1980) 109 Cal.App.3d 933. The Lindsey decision was upheld in the California Supreme Court case of City and County of San Francisco v. Sweet (1995) 12 Cal.4th 105. See also Lovett v. Carrasco (1998) 63 Cal.App.4th 48.)

The “made whole” doctrine

The “made whole” doctrine basically states that before a lien claim can be equitable, the third-party recovery must fully compensate the injured person for the total injury. Thus, if there is a policy-limit recovery by the injured person, for example, that does not adequately pay for the entire injury claim, the client has not been “made whole.” The third-party recovery must make the insured whole, before the injured insured is obligated to reimburse the insurance company that paid the medical bills for the injury. (See discussion of the made whole rule in California in the California Supreme Court case of 21st Century Insurance Company v. Superior Court (Quintana) (2009) 47 Cal.4th 511.)

Quintana held that attorney fees and pro rata litigation costs cannot be deducted from the entire recovery, in determining whether the injured insured, in an automobile medical payment reimbursement claim, was made whole. Such pro rata deduction for fees and costs are allowed, however, under the “common fund” doctrine.

The Quintana Court generally recognized that an injured insured must be “made whole,” before the medical payment carrier is entitled to reimbursement. Thus, the value of the case must exceed the value of the case and the lien claim. The Court specifically noted that its decision has application only to automobile medical-payment cases: “The reason is that automobile insurance coverage may differ in scope from coverage under other liability policies or homeowner’s insurance that may or may not have reimbursement provisions, insurer participation requirements, or definitions that apply only to the particular insurance policy.” (Id. at p.536, fn. 1.)

For a historical study of the made whole rule, see Allstate Insurance Company v. Superior Court (Delanzo) (2007) 151 Cal.App.4th 1512. (See also Progressive West Ins. Co. v. Superior Court (2005) 135 Cal.App.4th 263, 273, which held the made whole doctrine applicable to med-pay reimbursement claims.)

Some insurance carriers have contractual provisions giving the carrier priority rights to the recovery. (See Samura v. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc. (1993) 17 Cal.App.4th 1284, 1297.) Thus, the priority rights established by contract may preclude the made whole doctrine. The carrier would, contractually, be entitled to payment of the entire lien claim, before the client receives distribution.

Since the holding of Samura, the California Legislature passed limitations and caps on the amount of recovery allowed by health care providers such as HMOs. (See Civil Code section 3040, discussed below.)

The issue of whether there should be a deduction from uninsured motorist benefits for previously paid medical payments is frequently raised. In Security National Ins. Co. v. Hand (1973) 31 Cal.App.3d 227, 231-232, involving payment by a concurrent tortfeasor, the made whole doctrine was applied. (Also see CSAA v. Huddleston (1977) 68 Cal.App.3d 1061 United Pacific Reliance Ins. Companies v. Kelly (1983) 140 Cal.App.3d 72 and Kelly v. Farmers Ins. Exchange 1987) 194 Cal.App.3d 1.)

Other important California cases discussing the made whole doctrine are: Plut v. Fireman’s Fund Ins. Co (2000) 85 Cal.App.4th 98 – home insurance; Progressive West Inc. Co. v. Superior Court (2005) 135 Cal.App.4th 263 – automobile medical payment reimbursement not permitted unless injured party is made whole; Sapiano v. Williamsburg National Insurance Company (1994) 28 Cal.App.4th 533 – property damage not made whole; and Samura v. Kaiser Foundation Health Plan, Inc., (1993) 17 Cal.App.4th 1284 – HMO liens exclusive of made whole right of injured party.

Attorney obligation to honor the med-pay lien claim

The case law on the issue is mixed. According to one old case, there need not be a signature of the attorney to bind the attorney to the contractual lien claim payment requirements. (See Kaiser v. Aguiluz (1996) 47 Cal.App.4th 302 [Disapproved on procedural ground in Snukal v. Flightways Manufacturing, Inc. (2000) 23 Cal.4th 754], where an attorney was held liable for the entire known lien claim.)

Compare the Aguiluz case, however, to cases involving automobile reimbursement contractual provisions in Farmers Insurance Exchange v. Zerin (1997) 53 Cal.App.4th 445 and Farmers Insurance Exchange v. Smith (1999) 71 Cal.App.4th 660. The Farmers cases found no equitable lien for the lien holder against the injured party’s attorney. The two courts found the plaintiff’s attorney not to be a collection agent for the insurance company. In Smith, the court strongly refuted the conclusion of Aguiluz, that an attorney with knowledge of a lien is personally liable for the lien. The Court explained, however, the injured party remained liable to pay the billing before and after distribution of settlement funds.

Attorney fee has priority over medical lien

The basic rule is a lien first created has priority over later created liens. (Civ. Code, § 2897.) Unless an attorney signs an agreement to pay a medical lien claim from the proceeds of a settlement and thereby creates a fiduciary duty owing to the medical lien provider, an attorney fee lien has priority over a medical lien claim regardless of the time the liens are created.

“[A]s a matter of law, the amount recovered by the Plaintiff in a personal injury lawsuit always goes first to satisfy the attorney lien for fees and costs before is it used to satisfy medical liens,” (Gilman v. Dalby (2009) 176 Cal.App.4th 606, 620.) Gillman explained: “In sum, an attorney lien for fees and costs is essential: 1) to ensure that injured persons can obtain legal representation in lawsuits to obtain adequate compensation for injuries they have suffered; 2) to hold tortfeasors accountable for the harm they have caused, and 3) to provide medical lien holders with a source for compensation that they otherwise might not have. Thus, public policy and equity favor an attorney lien for fees and costs priority over a medical lien, regardless of which lien was first in time.”

Case law allowing for reduction of attorney fees and costs can be found in Quinn v. State of California (1975) 15 Cal.3d 162 for workers’ compensation actions; Summers v. Newman (1999) 20 Cal.4th 1021 for workers’ compensation settlements; Lee v. State Farm Mut. Auto Ins. Co. (1976) 57 Cal.App.3d 458, 466-469 and 21st Century Ins. Co. v. Superior Court (Quintana) (2009) 47 Cal.4th 511 for automobile medical payment liens.

Aggressive collection tactics by insurance carriers

There are two things essential in dealing with automobile med-pay lien claim insurance carriers or their collection agency… First, early-on and throughout representation, the client must be made aware of a potential med-pay lien claim and be prepared to pay it at time of settlement; and, second, the med-pay carrier must be advised of a settlement to avoid aggressive collection efforts against the injured client for non-payment of the lien. Lien claims are frequently negotiated down, and certainly, under the made whole doctrine explained above, there may be a complete waiver of the lien claim.

Most policies offering med-pay will have a right of reimbursement written into the policy language. However, there are still a few that do not have a right of reimbursement. Count yourself lucky if your client has one of those; they do exist but there are not many of them.

Request a copy of the contract language and read it carefully to see if the policy does in fact have a claim for reimbursement.

Conclusion

Ensuring you are aware of the med-pay provision is essential in resolving a dispute. It’s important to read the contract and understand the responsibility it imposes on your client and yourself.

Sergio Julian Puche

Sergio Julian Puche represents individuals against corporations in employment and personal injury cases. Throughout Mr. Puche’s legal career he has advocated for consumers. Mr. Puche attended law school at California Western School of Law. He has practiced at the Law Offices of Mauro Fiore, Jr., APC since May of 2013. Mr. Puche resides in Pasadena, California with his dog, Ezra.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine