Effective storytelling and your discovery plan

A step-by-step approach to creating a discovery plan so you can tell your client's story at trial

As litigators and trial attorneys, we are consumed with deadlines, meetings, working-up our cases, exploring settlement at mediation, getting our cases ready for trial when settlement is not an option, and going to trial. Throughout the discovery process, it is important to keep in mind that we need to tell our client’s story. If you are a litigator, you are a storyteller. Effective storytelling is tied into the development of a discovery plan. A discovery plan begins with our client’s story. Bringing a client’s story to life for a jury is essential for a trial lawyer.

In implementing your discovery plan, determine what is needed to tell your client’s story. You must have a thorough knowledge of the case. Effective discovery requires planning and coordination. A discovery plan is an essential part of effectively implementing the best use of formal and informal discovery methods. You need a good road map. A litigation discovery plan provides the scope of discovery and a timeline for implementing the discovery to support legal theories, remedies and to counter defenses.

Preparing a discovery plan

There is no right or wrong way to prepare a discovery plan. A discovery plan should be well organized for use by the attorney and staff. As the attorney working up the case, the discovery plan has to make sense to you. However, it should equally make sense to anyone working on your team such as a young associate, the head partner, your legal assistant or paralegal. The format or length of your discovery plan will depend on the type of case and the complexity of the issues. It also depends on the facts that are available. In a medical negligence or product liability case, your discovery plan may require more detail. In a more straightforward case, your discovery plan may be short or simplified.

Timing

Start preparing a discovery plan early. A good time to start preparing a discovery plan would be right after signing up the client. Ideally, you should have your discovery plan ready to be implemented once the lawsuit is filed.

What to include in a discovery plan

When putting together a discovery plan, consider the following:

• Develop the theory of your case

Research the law and identify the legal theories that apply to your case. Are there multiple theories? Determine the strengths and weaknesses of each theory. If your case involves an area of the law that you are unfamiliar with, then study the concepts. Reaching out to colleagues who specialize in the area or handle those types of cases will help. Listservs are a great way to get input. Also, consider reviewing legal briefs in document banks that address the legal theories you are considering in your case.

• Identify the legal elements

It is very important that you begin with the jury instructions. Figure out what exactly the jury will have to decide at the end of the trial. This will be your roadmap and guide. Just as you would figure out the directions to your destination before you drive your car, the same is true with having a roadmap for what you’ll need to prove in your client’s case to prevail in the end. The jury instructions will provide you with the legal elements that are essential to establish the liability and damages issues which can be supported or defended in your case.

Review the CACI jury instructions because they will serve as a blueprint. If any special jury instructions are needed, then figure them out in the beginning of the case as a roadmap for gathering facts that are needed to prove your case.

• Organize the facts

Identify the facts which are necessary to establish each element of a legal theory. What are the facts needed to establish each claim or defense? Figure out the facts you have to support your case. Consider preparing a chronology to organize the facts. A chronology is a good way to identify gaps and holes in your timeline. The chronology will also alert you to facts that need to be investigated further.

It is also helpful to identify the good and bad facts. The bad facts cannot be ignored, so it is best to face them head on when preparing your discovery plan. Also, analyze the strengths and weaknesses of your case when applying the facts to legal elements.

• Identify the key players and witnesses

Not only is it important to know who your client is going to sue, but it’s equally important to understand why your client is suing them. Assembling a complete list of witnesses is also essential. The list of parties and witnesses will give you an idea of the depositions you will need to take in a given case. Be overinclusive in creating the list of witnesses. You can always decide at some point that the depositions of all witnesses might not be necessary.

Additionally, as litigation begins and progresses, the depositions of some parties or witnesses may lead to other names being added to the list of potential deponents. For example, in a drowning case, an incident report may provide you with the names of other individuals who were in the pool with the decedent. By interviewing those witnesses, you may learn that there were other individuals in the pool who were not identified in the incident report. You may want to interview those individuals and also take their depositions.

• Figure out documentary evidence

Chart out how the evidence meets the burden of proof. Identify all documentary evidence that is needed to support the liability and damages issues in the case. Figure out the strengths and weaknesses of each. Also, determine which documents are needed to counter the other side’s affirmative defenses. What usually happens is the other side will provide a laundry list of affirmative defenses in their Answer to the Complaint. However, not every affirmative defense will be applicable to the case. As litigation progresses, you will want to narrow down the affirmative defenses so you have an understanding of the key ones that do apply to the case. Even before you file a lawsuit on behalf of your client, you will already have an idea of what the viable defenses are in the case, which will be helpful when it comes to thinking about documentary evidence.

Consider creating two categories:

(1) Documents you already have and

(2) Documents you will need to obtain. Create a running list of documents. Furthermore, think about evidentiary issues in developing your discovery plan. Are there any admissibility issues with certain documents, and why? Will you have any difficulty laying a foundation with any documents and how will you get around those issues? Are there any authentication issues with some documents? If so, how will you address those issues? Perhaps, serving Request for Admissions will be the way to resolve any authentication issues.

The documentary evidence you will need to obtain depends on the type of case you have. Some examples of documentary evidence to consider are the following: witness statements, photographs, video recordings, police traffic collision report, fire incident report, other incident reports, 911 tapes from police dispatch, and property damage records, to name a few.

• Identify and evaluate the defenses

After identifying and evaluating the claims being asserted, go through the same analysis with the defenses to your client’s case. Consider the elements, facts and sources of proof. Determine what evidence will be necessary to counter your opponent’s case.

Group effort

• Brainstorm with others

Your discovery plan will change and go in different directions as you learn more about your client’s case. Throughout the development of your discovery plan, consider brainstorming with your colleagues and staff when you are struggling with any aspect of your case or to run ideas by them. Brainstorming is not limited to attorneys. You can involve your legal assistant, law clerk, paralegal, receptionist, file clerk or any other member of your team. They are all your potential jurors, so running ideas about different aspects of the case by them can be extremely helpful in fine-tuning your discovery plan and your case.

The brainstorming process can be fairly simple and inexpensive. You can buy lunch for your staff and present certain aspects of your case to them in the conference room. All you may need is a white board or butcher paper and markers. Provide your audience with a synopsis of your case. Let them ask you questions about the case. There are certain scenes of your client’s case or story they may find pertinent to the case and you will want to understand why. Each inquiry made by your staff or colleagues will give you a better idea of any facts or issues you need to explore further. If you are unable to answer some or many of their questions, then you will need to figure out how to obtain that information – from your client, from depositions, from document demands or other sources.

• Working groups

Take the brainstorming process a step further and meet with other attorneys in working groups. Meeting once a month or every other month with attorneys to work on different aspects of a case will provide you with invaluable insight. Is there something you overlooked? Is one of your colleagues suggesting you take a different angle and providing you with the reasons for that suggestion? The information you learn from the working group will help you to adjust your discovery plan. You may learn from the working group that they think it is important to hear from certain witnesses from the defendant company about policies and procedures or other documents. This will help you refine your discovery plan. You may need to send out request for production of documents to the defendant company so you can obtain the documents you will need to question a deponent about ahead of time.

Also, working on trial skills in the group will help you refine your discovery plan. For example, if you are struggling with a piece of the story that was provided to you by your client, you can get input from the working group. You may then want to address that issue by doing a mock voir dire on a topic with the working group members who are playing the roles of your potential jurors. By obtaining insight ahead of time, even before you file the lawsuit in the case, you can tweak your discovery plan and explore certain issues further and figure out how to go about getting information or documents you need to support or defend those issues.

• Informal focus groups

Reach out to members of your community or other communities to get their input on different concepts, ideas, or problems with your case. You can conduct an informal focus group which will help you with the development of your discovery plan and case. For instance, if you go to your local Starbucks, you can offer to buy a handful of customers a cup of coffee or tea in exchange for getting their input on an issue, concept or idea for about twenty minutes. They can provide you with invaluable input for a minimal price.

• Family and friends

Your family and friends can give you a different perspective and different ideas that you can explore in discovery. The insight that family and friends provide to you will allow you to make any necessary adjustments to your discovery plan.

Determine the sources of proof

Break down the sources of proof into two categories: (1) informal and (2) formal.

Informal sources of proof

Start with your client

Most of our clients have never been involved in a lawsuit before. The legal process is entirely new to them. They are not seeking our advice and professional services because something good happened to them. Quite the opposite – something traumatic, and often tragic, has happened to them. Whether they are dealing with their own injury, the loss of a loved one, or the loss of a job and livelihood, the situation is bad. They are usually struggling – physically, mentally, financially or a combination of the three. Not only are they overwhelmed by the traumatic changes in their lives, they are concerned about the added responsibilities of having to be involved in litigation. They do not want to say or do the wrong thing. They do not want to do something that will hurt the case or upset their attorney.

As litigators and trial attorneys, we are consumed and, at times, overwhelmed, with deadlines, being pulled in different directions and we have many demands and responsibilities in and outside of our careers. Because of our hectic schedules, we may choose to have as many meetings as we can take place in our office rather than having to travel all over the place. The same is true when it comes to meeting with our clients.

Simply meeting with our clients at our offices is depriving us of the opportunity to truly get to know our clients. To gain a thorough understanding of what our clients have gone through and what they will likely be going through for the rest of their lives, it is essential that we spend time with our clients at their homes. Our clients are in their own element when they are at home. They tend to open up so much more when we are sitting with them and talking to them in their own home. We can spend time with our clients on any day or evening of the week while we are in less formal clothes instead of in business suits or other clothing that screams “lawyer.”

By spending time at our clients’ homes, we will be able to make many observations including pictures on the walls, the types of books on the shelves, photo albums that our clients forgot about because they are tucked behind some blankets on the top shelf of a closet, or video recordings saved on a home computer. We may come across letters, journals and other documents that would be helpful or important to the client’s case. We will have the opportunity to look through all parts of a client’s house to learn more about them or a loved one who died. We can learn so much more about a client and discover treasures that will be helpful to a case by simply going to a client’s home and spending time getting to know them and family members. More importantly, the experience will help us to put ourselves in our clients’ shoes and bring their stories to life at trial, at a mediation, and develop those stories before and through the discovery process.

Simply having our clients provide us with information by completing questionnaires and other paperwork and gathering documents for us based on a list of items we give to the client, will not give us an understanding of their full story. Our clients may not know what information or documents we really need. They may not know that the photographs hidden in a box in the back of a closet in their hallway are really helpful to their case or how they are relevant to issues in the case.

Our clients are a great source of information. To truly understand our clients’ stories, it is important that we spend time visiting with our clients at home. We develop a better understanding of our clients’ lives by experiencing a part of it with them. Having a complete understanding of what our clients go through on a daily basis and learning from them about what they have lost will help us to translate those losses to a jury.

Client’s family/friends/colleagues

Talk to your client’s family, friends and colleagues to obtain further information about your client and your client’s case. They may be able to assist you in filling in any gaps in a chronology of facts that your client is unable to provide. They may also have additional information which is consistent with or contrary to what your client has told you. You may need to investigate further depending on the information you are provided by your client’s family, friends and colleagues. The family and friends may also have documents, photographs, video recordings or other information which may help you to explain your client’s story.

Other third parties

Businesses, stores and companies may also have information that will assist you with your client’s case. In a premises-liability case, a store or business owner may have security videotapes that you will want to review. Individuals who were in the store at the time of the incident may also have videotape footage. Your review of the videotape footage may lead to questions that you will need to investigate further in order to find the answers.

Other sources

Public records and other sources should be considered as part of your discovery plan. The internet, social media and listservs are great tools for finding information. If you have a wrongful death case, obtaining death certificates and autopsy reports is helpful with causation issues. By reaching out to listservs and similar resources, you can obtain prior testimony from defendants, their employees, if you are suing a company or corporation, and others that may lead you down a different road and require you to obtain additional information concerning issues in your case through interrogatories or request for production of documents.

Experts

Get experts involved early on, if you can. Experts can provide guidance about documents you need to request and information you need to obtain from various sources, including from your client. Experts can also help you to tailor written discovery inquiries. They can also give you input on depositions to take and areas of questioning.

Formal sources of proof

Select the proper discovery methods to get the job done. When you are formulating the areas of inquiry, consider which discovery tools will be the most effective. As you gather information, you will refine your discovery plan.

Deposition

Think about the depositions you should take in a case and understand why you need them. Determine the number of depositions you will need to take and the documents you will need to obtain ahead of time, such as policies, procedures and bylaws, versus which documents can be produced on the date of the deposition. If you are unable to get what you need by noticing the deposition of the defendants, then serving deposition subpoenas on third parties may be necessary. Carefully tailor request for production of documents in a deposition notice or a deposition subpoena.

Before you take any depositions, you need to have a thorough knowledge of the facts. Keep that in mind when preparing your discovery plan. If the case involves having an extensive knowledge of medicine, then you will need time to educate yourself and meet or have conference calls with experts who can assist you in learning about complicated or difficult issues. Your review of the medical literature may generate more questions you will need to ask at the depositions.

Written discovery

Before you file any lawsuit, figure out what evidence you will need to get from written discovery. The types of written discovery to consider are: (1) Interrogatories [C.C.P. §2020.010 et seq.] (form, special, contention); (2) Demand for Production of Documents and Things [C.C.P. §2031.010 et seq.]; (3) Request for Admissions [C.C.P. § 2033.010 et seq.]; and (4) Demand for Site Inspection. In a personal injury case, defendants usually serve a Request for Physical or Mental Examinations [C.C.P. § 2032.020 et seq.]. Obtain a copy of any report from the defense medical examination (DME). Your review of the DME may raise issues that you need to investigate further through the discovery process. Your experts should also review the DME report. They can identify areas of inquiry you will need to investigate further.

Consider whether you will really get everything you need from written discovery. How long will it take to get what you need from written discovery? The written discovery process can be time-consuming. First, you’ll want to tailor your discovery inquiries in a manner that will maximize your chances of actually getting what you ask for. Second, opposing counsel will likely ask for an extension to provide verified responses. Third, you can anticipate receiving all objections or, at the very least, the majority of the responses will be objections. You will then need time to go through the meet and confer process. Sending a meet and confer letter is usually not sufficient. Judges want more effort which could include phone calls or sending emails to opposing counsel. If you are in a jurisdiction that requires an informal discovery conference (IDC), then that will add another step. Also, you may not be able to get a date for the IDC for a long time. Finally, if the discovery dispute cannot be resolved informally, you will need to file a motion to compel. However, getting a hearing date for the motion can be difficult. Some courts may not have a hearing date available for months. By the time you receive meaningful verified responses, many months could go by.

Budget

Form Interrogatories, Special Interrogatories, Demand for Production of Documents and Things and Request for Admissions are fairly inexpensive discovery tools. It does not cost a lot to propound written discovery.

Depositions, on the other hand, can be expensive, especially if your list of deponents is long. Although it can be costly to take more than several depositions, you can learn a lot from the witness and the notice requirement is only 10 or 15 days, depending on whether you personally serve the deposition notice or place it in the mail. You may be able to get what you need on a quicker basis by taking depositions.

Using a combination of discovery tools while keeping a budget in mind is a good approach. The higher the value of the case means a bigger budget when it comes to the number of depositions you can take in a given case in conjunction with the written discovery you serve and the motions to compel you’ll need to file.

Timing

Carefully consider the sequence and timing involved in the discovery process. Keep the following deadlines in mind when formulating your discovery plan:

• Discovery cut-off

• Motion cut-off

• Completing the discovery needed in a case to effectively oppose a motion for summary judgment or a motion for summary adjudication.

• Serving discovery early enough so you have time for extensions, the meet and confer process and discovery motions and hearing dates.

• Having enough time to obtain documents you will need before taking depositions.

• Getting all the admissible evidence you will need for trial.

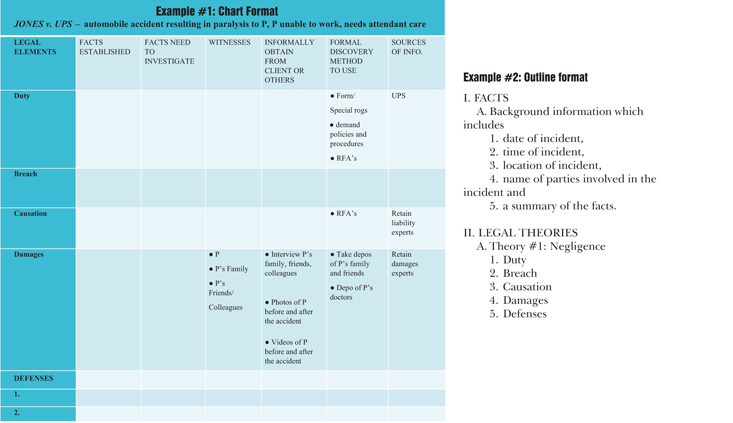

Different forms of discovery plans

Remember our law school days when many of us created outlines to prepare for examinations? Others prepared flow charts or note cards. No matter what we did to prepare for our final exams, it was important that we used the method or technique that worked best for us to understand and retain the necessary information. The same is true when it comes to creating a discovery plan. Use whatever method works for you, but allows all of the information to be displayed in a well-organized manner. Consider preparing tables, checklists, outlines, charts, or simply keeping a notebook to write notes in to keep track of what information or documents you need to request or obtain.

You may find the included examples of discovery plans helpful.

Conclusion

The goal in creating a discovery plan is to find the format that works best for you and is well organized. The discovery plan will change as you continue to obtain new information and gather evidence. Be flexible throughout the development of your discovery plan and keep making adjustments along the way. Making the time to create a discovery plan will keep you on track and guide you down a successful path.

Elizabeth A. Hernandez

Elizabeth A. Hernandez is an attorney at BD&J, PC in Santa Monica. Her areas of practice include catastrophic injury and wrongful death cases. She is the 2025 CAALA president-elect. She was the 2022 recipient of the CAOC Robert E. Cartwright, Sr. Award, given in recognition of excellence in trial advocacy and dedication to teaching trial advocacy to fellow lawyers and to the public. She may be reached at BD&J, PC at elizabethhernandez.caala@gmail.com.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine