Medical leaves

The interplay of CFRA, FMLA, PDLL, and FEHA in your pregnancy/family-leave case

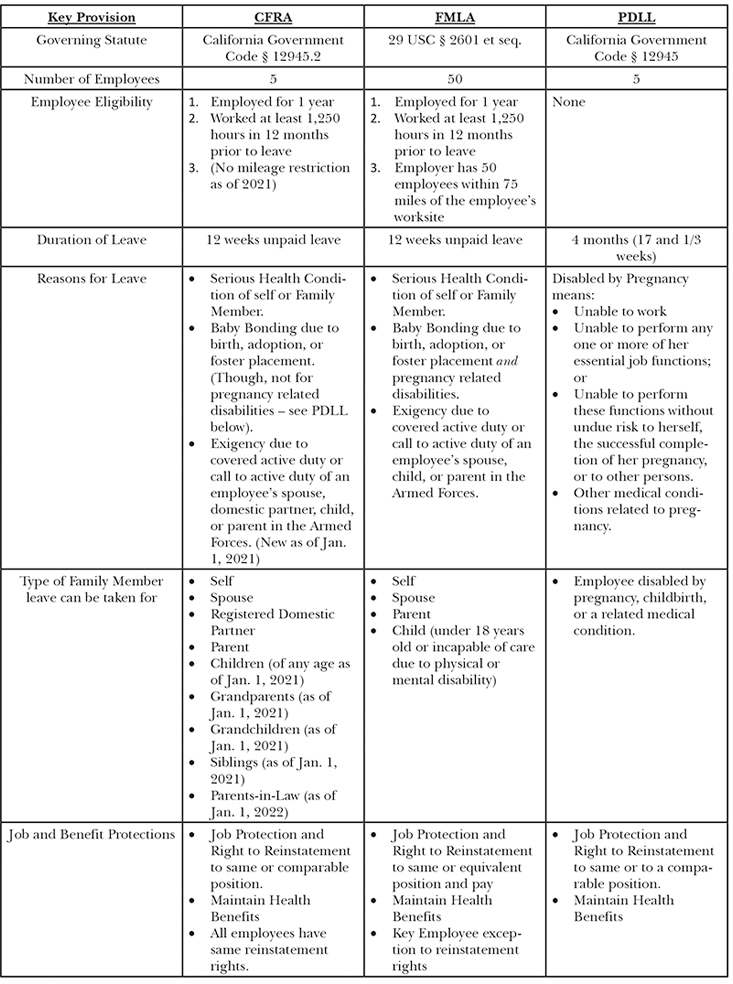

Numerous laws exist in California that provide for some sort of leave of absence from employment. The main ones are the California Family Rights Act and its federal corollary the Family Medical Leave Act, the California Pregnancy Disability Leave Law, and, though not a “leave law,” a reasonable accommodation leave under the Fair Employment and Housing Act. Knowing which one applies, when to use one, and how they overlap is critical in evaluating and litigating leave cases.

First, we will explain these major leave laws and when an employee is eligible for utilizing each type of leave. Second, we will briefly lay out what is needed to establish a violation of these laws. Finally, we will debunk a few examples of typical defenses to these claims and illustrate how drawing it out helps to visualize if a violation occurred.

The CFRA and the FMLA

The California Family Rights Act, more commonly known as the CFRA, is California’s corollary to the federal law, the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Both these laws provide for 12 weeks of unpaid leave during a single year. They also both allow for employees to take intermittent leaves – like when an employee needs a week off each month for chemotherapy treatment or if they have other chronic conditions that flare up from time to time. While the two are very similar, they differ in several significant ways.

Who is eligible for CFRA or FMLA leave? This is one of the key areas where the two laws differ. As of January 1, 2021, the CFRA now applies to private employers who have five or more employees. (Gov. Code, § 12945.2, subd. (b)(3).) Prior to 2021, the CFRA only applied to private employers with 50 or more employees, just like the FMLA. This is a huge expansion of eligibility for employees in California. In addition, before 2021, there needed to be 50 employees within 75 miles of the employee’s worksite. This requirement has now been eliminated in the CFRA but still applies under the FMLA. (Gov. Code, § 12945.2(b).) These two changes greatly expanded coverage and eligibility for California employees.

However, under the new CFRA provision reducing the number of employees, if an employer has between five and 19 employees, then a pre-lawsuit attempt at mediation through the California Department of Fair Employment and Housing is required before the employee can file their case in court. (Gov. Code, § 12945.21.0) This mediation demand must be made by the employee within 30 days of receiving the right to sue notice. (Ibid.) The demand for mediation tolls the statute of limitations until the DFEH completes the mediation. (Ibid.) This requirement is currently in place until January 1, 2024. (Ibid.)

Another area the laws differ is in the reasons for leave. Both the CFRA and the FMLA allow for leave for a person’s own serious medical condition and serious health condition of certain family members. However, the CFRA has a much more expansive definition of “family member” that enables people to take medical leaves in a larger variety of circumstances. (Gov. Code, § 12945.2, subd. (b)(4)(B).) For example, the definition of child in California includes any child, regardless of their age and regardless of their disability status. But under the FMLA, “children” means under the age of 18 or is physically incapable of self-care due to a physical or mental disability.

As of January 1, 2021, the CFRA also covers adult children, child of a domestic partner, grandparents, grandchildren, and siblings. These family members are not covered under the FMLA.

What is a serious health condition? A serious health condition is an illness, injury, impairment of physical or mental condition that involves either (A) inpatient care in a hospital, hospice, or residential health care facility; or (B) continuing treatment or continuing supervision by a health care provider. (Gov. Code, § 12945.2, subd. (c)(3)(C) and 2 CCR § 11087 (q).) This is very similar to the FMLA, however, under the FMLA, inpatient care requires an overnight stay whereas the CFRA does not (so long as at the time the patient went to the hospital it was expected that they would stay overnight, even if it later turns out they didn’t stay the night for a variety of reasons).

The other key difference between the CFRA and FMLA is in reinstatement rights. As of January 1, 2021, the CFRA eliminated the key-employee exception that allowed employers to avoid the right to reinstatement for certain of the employers’ highest paid employees. Now, under the CFRA all employees have the same reinstatement rights. However, under the FMLA, the key-employee exception still exists.

Pregnancy Disability Leave Law (PDLL)

In California, pregnancy-related disability leaves, childbirth, and related medical conditions are covered by the California Pregnancy Disability Leave Law (PDLL). (Gov. Code, § 12945, subd. (a).) This leave provides for four months of leave, which is defined as 17 and 1/3 weeks for a full-time employee. (Ibid.; 2 CCR § 11042(a)(1).) If an employee works more, or less, than 40 hours per week, then the number of working days to equal four months is calculated on a pro rata basis. (2 CCR § 11042(a)(2).)

In California, the CFRA does not apply for pregnancy-related disabilities/childbirth. (2 CCR § 11046(a).) Rather, the CFRA is used only for 12 weeks of baby-bonding time. Thus, if an employee uses up all four months of leave due to pregnancy/childbirth, they still have 12 weeks left of baby-bonding time. (2 CCR § 11046(c).) In total, an employee who qualifies for both the PDLL four months of leave and the 12 weeks of CFRA baby-bonding leave, would be eligible for seven months (29 and 1/3 workweeks) of leave. (2 CCR § 11046(d).) The 12 weeks of FMLA time that would apply runs concurrently with the four months of time provided for pregnancy-related disability leaves under the PDLL.

However, as noted below, the FEHA right to reasonable accommodations in the workplace due to an employee’s physical or mental disability has no week or month requirement or limitation. Thus, the right to a leave of absence as a reasonable accommodation is separate and distinct and must be determined on a case-by-case basis. (2 CCR § 11047.) (See e.g., Sanchez v. Swissport, Inc. (2013) 213 Cal.App.4th 1331, 1339-1340 [employee disabled by high-risk pregnancy also entitled to FEHA leave in addition to PDLL leave].) This means an employee could be out on a pregnancy leave for even longer than seven months.

The definition of “disabled by pregnancy” is very broad. It includes if, due to the pregnancy, the employee (1) is unable to work, (2) can’t perform an essential function(s) of her job, (3) working would risk herself or the pregnancy, or (4) any other circumstances the doctor considers disabling. As to this fourth category, the regulations also include a non-exhaustive list of instances: “[a]n employee also may be considered to be disabled by pregnancy if, in the opinion of her health care provider, she is suffering from severe morning sickness or needs to take time off for: prenatal or postnatal care; bed rest; gestational diabetes; pregnancy-induced hypertension; preeclampsia; post-partum depression; childbirth; loss or end of pregnancy; or recovery from childbirth, loss or end of pregnancy. The preceding list of conditions is intended to be non-exclusive and illustrative only. Nothing in this Article shall exclude a transgender individual who is disabled by pregnancy.” (2 CCR § 11035(f).) As such, there are innumerable instances where an employee will qualify for a leave of absence and be afforded job protection.

The Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA)

While not a leave law entitling an employee to a certain number of weeks or months of leave, the California Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA) is of critical importance to all the leave laws. This is because the FEHA requires an employer to provide reasonable accommodation(s) for employees with physical or mental disabilities. (Gov. Code, § 12940, subd. (m).) Under this law, a leave of absence is considered a type of a reasonable accommodation. (2 CCR § 11068(c).) “Holding a job open for a disabled employee who needs time to recuperate or heal is in itself a form of reasonable accommodation and may be all that is required where it appears likely that the employee will be able to return to an existing position at some time in the foreseeable future.” (Jensen v. Wells Fargo Bank (2000) 85 Cal.App.4th 245, 263.) Thus, at the conclusion of a CFRA, FMLA, or PDLL leave, or to fill a gap period, a leave of absence could be provided under the FEHA. However, the providing of a reasonable accommodation under these circumstances could mean that an employee may lose their right to reinstatement.

What is needed to have a case for violation of these laws?

There are two different types of violations of the CFRA, FMLA, and PDLL. An employer can (1) interfere with an employee’s right to protected leave or (2) they can retaliate/discriminate against the employee for having taken that leave.

Under an interference claim, a violation simply requires the employer deny the employee’s entitlement to leave. (Faust v. California Portland Cement Co. (2007) 150 Cal.App.4th 864, 879 [denial of CFRA leave was improper].) No intent is required. (Ibid.) Examples of interference claims include denying the right to take a leave, terminating an employee while on leave, not reinstating an employee at the end of their leave, as well as discouraging employees from using leave. (2 CCR 11094.)

In these interference instances, however, an employer’s intent or honest mistake does not matter. Employers are liable for their mistake in calculation or in determining that the employee was not eligible.

Also, an interference claim does not invoke the burden-shifting analysis of the McDonnell Douglas test. (Moore v. Regents of University of California (2016) 248 Cal.App.4th 216, 250.) This means that an employer’s claimed legitimate reason for terminating the employee, or their mistaken but honest belief that the employee was not eligible for leave, does not apply. If the employee can show

(1) they were eligible for the leave,

(2) requested or took the leave, and

(3) they were denied the leave or reinstatement right, then they have proved a violation of the law.

However, for retaliation cases, the employee must show that (1) the defendant was a covered employer, (2) the employee was eligible to take the leave they requested, (3) Plaintiff exercised their right to take the leave, and (4) some sort of adverse employment action (i.e., termination, suspension, fine, etc.). (Soria v. Univision Radio Los Angeles, Inc. (2016) 5 Cal.App.5th 570 (CFRA case).) In those circumstances, just like in any other FEHA retaliation case, the plaintiff will need to show intent – that the employers stated claimed reason for termination was a pretext. (Moore v. Regents of Univ. of Calif., supra, 248 Cal.App.4th at 248-250.)

Some typical defenses debunked

In many of these leave cases, employers tend to argue that the paperwork was not sufficient, they were not aware of the need for the leave because the papers were submitted to a third-party administrator, or that the employee did not use the correct form. None of these are valid defenses. In fact, once an employee has submitted a proper request for CFRA leave, the employer is charged with knowledge that the CFRA protects the employee’s absences. An employer who fires an employee for such absences is liable for retaliation even if the employer thought the employee’s absences were unexcused. (Avila v. Continental Airlines, Inc. (2008) 165 Cal.App.4th 1237, 1260.)

Importantly, employers cannot require a specific form be used to certify a serious health condition. Regardless of whether the employer’s preferred form is used, or if an employee submits a note from a doctor on a separate piece of paper, the employer must accept as “sufficient” any “written communication from the health care provider” that contains: (1) date of onset, (2) probable duration, and (3) a statement that the employee is unable to work or perform any one or more of the essential functions of his position. (Gov. Code, § 12945.2, subd. (k)(1).) The note from the doctor could be on a letter, an email, a prescription pad paper, or any other written form of communication. Once an employee provides sufficient notice, they do not have any obligation under the statute to provide additional information unless asked. (2 Cal. Code Regs., § 7297.4(a)(1); Avila v. Continental Airlines (2008) 165 Cal.App.4th 1237, 1257-58.)

In addition, there is no special way an employee must request CFRA or other types of leaves. To notify an employer of a need for a protected absence, an employee need only provide verbal notice and need not expressly assert rights under the CFRA or FMLA or even mention the CFRA or FMLA, but may only state that leave is needed for a qualifying reason. (2 Cal. Code Regs. § 7297.4(a)(1); Faust v. California Portland Cement Co. (2007) 150 Cal.App.4th 864, 879-881.) No magic words or reference to the PDLL, CFRA, or FMLA are required.

Nowadays, many employers use third-party administrators for their leave management or to handle employee workers’ compensation claims. In those cases, employers have tried to claim they were not aware of the need for the leave (or an extended leave) because the information was not in their possession. Wrong. Employers are charged with the knowledge of their agents. (California FEHC v. Gemini Aluminum (2004) 122 Cal.App.4th 1004; Freeman v. Superior Court (1995) 44 Cal.2d 533 [when an agent has acquired knowledge which he or she had a duty to communicate to his or her principal, a conclusive presumption arises that the agent performed that duty].) If the need for the leave was submitted to the employer’s agent, the employer cannot avoid liability on these grounds.

What about where an employer claims that they fired the employee for collecting too many absences? If the absences were protected, or would have been protected had the employer properly designated them, then the employer is liable for a violation. An employer cannot apply a leave policy where an employee is fired for absences that are protected. Section 825.220(c), title 29 of the Code of Federal Regulations provides: “[E]mployers cannot use the taking of FMLA leave as a negative factor in employment actions, such as hiring, promotions or disciplinary actions; nor can FMLA leave be counted under ‘no fault’ attendance policies.” The CFRA also prevents employers from counting CFRA leave as absences under a no-fault attendance policy. (Avila v. Continental Airlines, Inc. (2008) 165 Cal.App.4th 1237, 1253-1254; see also 2 CCR § 7297.10 (incorporating FMLA regulations consistent with CFRA); see also Dudley v. Department of Transportation (2001) 90 Cal.App.4th 255, 264-265.)

Draw it out!

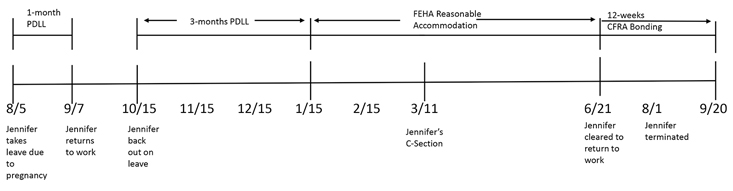

Whenever we receive calls from employees who have taken leaves of absence(s), we draw them out visually. Sometimes an intermittent leave is provided, and the employee took off numerous times over the course of the year. Other times, like with a pregnancy leave, it can involve both PDLL and CFRA leaves and the need for an FEHA reasonable accommodation. Visually drawing out the start and return to work dates helps to visualize and analyze these cases. So, how to handle and assess if a leave was properly given or not? Draw it out. Here is just one example where drawing out the timeline clearly illustrates the dynamics of these laws and where a violation occurred. Plus, it makes for a great demonstrative at trial!

Twins and a complicated pregnancy

Jennifer finds out in early August 2020 that she is pregnant with twins. Due to her age, and some other complications/concerns, her doctor puts her on bed rest. Jennifer submitted the forms and went on an approved leave from August 5, 2020 until September 7, 2020 and then returned to work for about a month before going out again on leave on October 15, 2020 for the duration of her pregnancy. Jennifer gave birth on March 11, 2021 to twins by C-section and her doctor continued her leave due to her C-section until May 5, 2021. On May 4, 2021, Jennifer’s doctor extended her leave again until June 20, 2021 due to further complications from her pregnancy. Jennifer was cleared to return to work as of June 21, 2021 and she requested baby-bonding time and that she would return to work on September 20, 2021. However, on July 15, 2021, Jenifer received a letter that she had exhausted all her leave as of March 15, 2021, was now on an unapproved leave, and needed to return to work immediately or would be terminated. Jennifer called human resources and explained she had no childcare and could not return right away due to needing to coordinate care and that she thought she had until mid-September for bonding time. On August 2, 2021, when Jennifer did not return to work that month, she was fired the same day.

In this scenario, as the chart above shows, the first period(s) of time, from August 5th to September 7th and then again from October 15, 2020 to about January 15, 2020, would be protected under the California PDLL. The twelve weeks provided by the FMLA would run concurrently to the PDLL leave. However, she was not due, and didn’t deliver, for another almost two months. And then, after her delivery on March 11, 2021, was not cleared to return to work for another three months, June 21, 2021. That period of time should have been covered under the FEHA as a reasonable accommodation. Some employers would argue that once the PDLL is exhausted, they can use CFRA to cover the next three months. However, because the CFRA explicitly excludes pregnancy-related conditions, Jennifer is not eligible for CFRA, her doctor still has her out due to pregnancy-related complications until June 21, 2021. As such, as of June 21, 2021 Jennifer now would be eligible to use her 12 weeks of CFRA baby-bonding time – which would have enabled her to be off on bonding time until about September 20, 2021. Her right to CFRA leave was interfered with and she should not have been fired on August 2, 2021.

Conclusion

This article and the chart on page 102 will be a useful road map to guide you and your clients through the maze of medical leaves and, in particular, the interplay of these leaves in the pregnancy context.

Martin I. Aarons

Martin I. Aarons has been an employment law trial attorney for more than 20 years. As a trial lawyer, Martin has handled all types of employment-related cases on behalf of people who have suffered a workplace injustice. He and his law partner, Shannon Ward, specialize in trials involving discrimination, sexual harassment, sexual abuse, retaliation and whistleblower cases of all kinds, shapes, and sizes. Martin was president of the Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles (CAALA) in 2025. www.aaronsward.com/

Shannon H.P. Ward

Shannon Ward is a partner at Aarons Ward where she focuses on cases involving harassment or abuse, discrimination, retaliation, and wrongful termination, along with her law partner Martin Aarons.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine