Big truck, big damages

Effective strategies in litigating catastrophic trucking cases

It’s an obvious but important maxim that each case is different and requires a tailored approach to discovery. In trucking cases particularly, a shotgun approach to discovery is a recipe for disaster that invites boilerplate objections and unproductive skirmishes. Wielding a scalpel in discovery requires a precise methodology, where every request is intentional and every inquiry has a clear goal that advances the case’s narrative. This isn’t just about gathering data, it’s about constructing an unassailable story. If it doesn’t advance the story, it’s a waste of time.

The blueprint: Regulations, records, and public intelligence

The Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) is the silent architect of trucking litigation. Understanding this framework is non-negotiable.

The SAFER System

Before formal discovery even begins, the FMCSA’s Safety and Fitness Electronic Records (SAFER) System (www.safersys.org) offers a goldmine of public intelligence. This online portal provides a “Company Snapshot” detailing a carrier’s identification, size, safety rating, roadside inspection summaries, and crash data. Searching by USDOT Number, MC/MX Number, or company name can reveal crucial operational details, such as the number of power units, drivers, miles logged, and total inspections. This readily available, credible data provides a baseline for anticipating potential areas of noncompliance and targeting specific requests.

Uncovering the truck’s secrets

FMCSA mandates rigorous record keeping. These documents can be critical evidence.

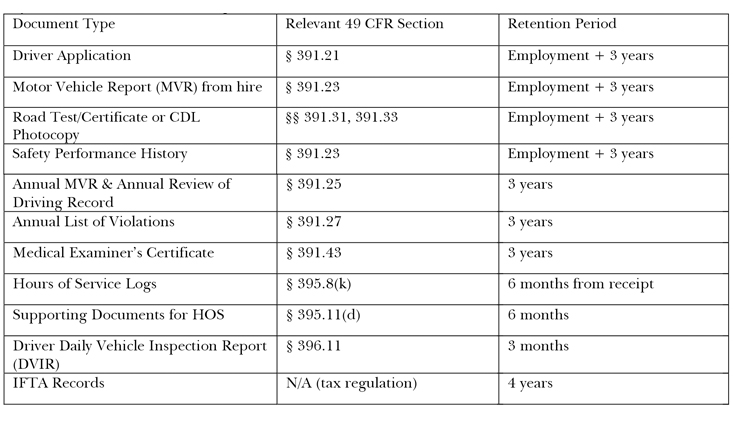

Driver qualification files (49 CFR § 391.51 & § 391.53)

These comprehensive files are a window into a driver’s history: job applications, Motor Vehicle Reports (MVRs), road test certificates, safety performance histories, annual reviews, violation lists, and medical certificates. Most must be retained for the duration of employment plus three years.

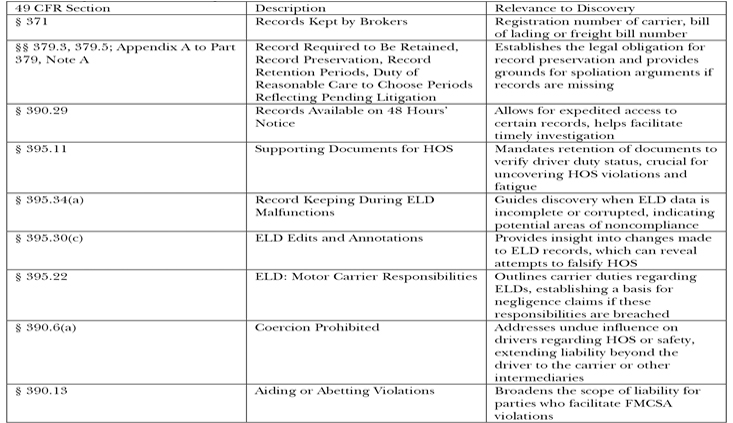

Hours of Service (HOS) records (49 CFR § 395)

Driver logs, whether paper or electronic, must be submitted to the carrier within 13 days and retained for six months. Crucially, these logs must be verified against supporting documents – up to eight per 24-hour duty period – including trip receipts, bills of lading, satellite tracking, and electronic control module (ECM) data. Discrepancies here are red flags for HOS violations and driver fatigue.

Vehicle inspection, repair, and maintenance (49 CFR § 396)

For vehicles controlled for more than 30 days, carriers must maintain detailed records of identification, inspection schedules, and all repairs. Driver-Vehicle Inspection Reports (DVIRs) are also vital; they document post-trip inspections and must be retained for three months.

International Fuel Tax Agreement (IFTA) records

Though tax-related, these records – retained for four years – offer granular data on trips, routes, and mileage, allowing for independent verification of HOS compliance and driver activity.

Electronic Logging Device (ELD) data

ELDs capture precise data, but regulations also cover malfunctions (49 C.F.R. § 395.34(a)), edits and annotations (49 C.F.R. § 395.30(c)), and carrier responsibilities (49 C.F.R. § 395.22). Raw ELD data, along with any changes, is a prime target for forensic analysis, and its erasure can lead to spoliation claims.

Navigating the maze of broker liability

The discovery process in trucking cases may reveal other potential avenues of liability beyond the traditional motor carrier. Freight and shipping brokers connect shippers with motor carriers to move goods. Use the discovery process to find facts supporting theories like negligent hiring, hidden motor carrier, or the existence of an agency relationship.

Requests for production of documents should include categories such as:

Contracts and agreements

A broker-carrier agreement outlines the relationship, responsibilities, and typically the independent contractor status. It can also reveal whether the broker assumed carrier duties.A shipper-broker agreement shows the services the broker promised to the shipper and how the broker held itself out.A shipper-carrier agreement (if your theory is that the broker acted as a motor carrier) is important for showing obligations such as providing vehicles, drivers, and ensuring compliance.Rate confirmation sheets can show the terms of specific loads and may contain language relevant to control or responsibility.Indemnification agreements indicate how the parties allocated liability.

Carrier qualification and monitoring files

Documentation related to the vetting process are used by the broker to qualify motor carriers and/or the specific motor carrier involved in your case. The broker will have policies and procedures detailing what information they gather and review, such as DOT number, operating authority, insurance coverage, and safety fitness rating.Safety information records are evidence of the broker having checked the carrier’s safety statistics, including reports or data pulled from FMCSA’s SMS.Insurance records not only confirm the carrier’s coverage but also show whether the broker continued to inquire as to the motor carrier’s insurance coverage.Operating authority verification is proof that the broker checked the carrier’s federal and state operating authority.Internal records of the broker’s dealings with the carrier in your case may reveal patterns or knowledge of issues.Records related to third-party companies hired to vet and/or monitor the carriers can indicate how thoroughly a broker vetted and monitored the motor carrier.

Load-specific documents

Bills of lading are crucial for identifying who was listed as the carrier for the load in your case and for previous loads with the same shipper to establish a course of dealing.Dispatch records and communications such as schedules, instructions, and any communications between the broker and the carrier or driver regarding the load can show how much control the broker exerted.Freight payment records show who was responsible for freight charges.

Operational and marketing materials

Website pages and ads show how the broker represents its services and can be used to argue they held themselves out as more than just a broker, potentially as a carrier (e.g., “truck services,” “handle your transportation needs,” “one-stop shopping for all transportation needs”).Forms used for accident reporting, vehicle inspection (if they exert such control), driver applications (if they are involved in that process).

Corporate/financial information

A broker’s operating authority, to determine whether they also hold motor carrier authority.A carrier’s financial records can reveal if they are unstable or fly-by-night, potentially indicating incompetence.

These comprehensive document requests will lay the foundation for establishing broker liability, and many of the categories sought here can be relevant in cases against motor carriers or shippers.

Artful discovery requires preparation

Effective discovery is an art form. Reusing old discovery from earlier cases might be good enough to cover the basics, but when the goal is to achieve an exceptional result, discovery should be tailored to the specific needs of each case and should go beyond the obvious.

Before drafting a single request, a deep dive into the foundations of the case is essential:

Jury instructions: Reviewing jury instructions before drafting discovery is like reading the test questions before the exam. They define the elements needed to win.

Mastering the rules of the road: FMCSRs are dynamic. Relying on outdated knowledge is perilous. Find the current specific regulations and agency guidance (e.g., carrier liability for falsified logs) applicable to each individual case.

Public information first: Gather all available public information, including news footage, security camera video, dash-cam, bodycam, 911 calls, radio logs, gate logs, documents subject to the California Public Records Act, and terminal inspection results. This independent, credible data provides an initial outline, highlights gaps, and saves resources. Don’t assume only one report exists; multiple agencies often have their own records.

Driver’s manuals and industry standards: Use driver’s manuals obtained in previous cases to craft discovery requests and create deposition outlines for the case at hand.

Witness insights: Talk to witnesses before drafting discovery. They can reveal unknown information and refine your case strategy based on actual facts.

Preservation and spoliation

In trucking litigation, evidence preservation is paramount. A meticulously drafted preservation letter, dispatched immediately post-accident, is the first line of defense. It must explicitly warn against spoliation and detail every record to be preserved: driver logs (six months), qualification files, email and other driver-dispatch communications, incident reports, compliance audits, trip receipts, bills of lading, satellite tracking, ECM data, maintenance records, and the physical equipment itself.

The destruction of evidence, especially after such a notice, can amount to spoliation and carries severe legal consequences, including an adverse inference jury instruction.

Putting it all together: Deposing the person(s) most knowledgeable/qualified

Whether this is your first or fiftieth deposition of a motor carrier’s person most qualified or 30(b)(6), what you need to accomplish and the sources of information that you will have available to you remain largely the same. The process of setting a PMQ deposition is one of the more painstaking endeavors.

The categories that you specify in your notice and corresponding documents you request must be tailored to the facts and legal issues in your case. We prefer an approach that is thorough and leaves no stone unturned without causing unnecessary delay. You must weave the FMCSA regulations into the categories designated in your notice.

There is significant benefit to serving your notices of deposition of the corporate defendant’s person most qualified, as well as the defendant driver, as close in time as the code permits after effecting service of process on the defendant(s). At this stage, you should already have FOIA/PRA requests pending. If the defense produces documents after you receive a response, you will have the ability to cross-reference what you’ve received to determine if the defendant(s)/their attorneys are hiding critical evidence.

When you receive the document dump, typically late the night before or early the morning of the deposition, the roadmap as to the issues you must cover are dictated by the universe of documents you receive: Driver qualification file, motor vehicle record, medical examiner’s certificate and the physical examination form, electronic pull notices, electronic driver logs, pre-trip inspections, telematics data, all videos originating from dashcam or in-cab monitoring, mandatory reporting involving fatalities and preventable collisions, every contract, the bill of lading, complete insurance coverage with corresponding declarations pages and policies.

Take the time to examine the witness regarding every document that was produced. You will educate yourself as to the internal hierarchy and business operation(s) of the carrier. Find out every person in the company’s hierarchy, what their duties and responsibilities are, and what involvement anyone in a leadership/supervisory role had in anything related to your case.

Depending on how well the defendant maintains records and the volume you are dealing with relative to when they were first produced, taking the 30(b)(6)/PMQ deposition early in the life of the case may put you at a tactical advantage if the defense witness testifies without fully understanding the full universe of information it has in its possession.

You also stand to establish on the record the documents and things counsel for the defense failed to produce. The byproduct will be reinforcing the consistent message to your opposing counsel (and insurance carrier) that you know how to handle a trucking file from top to bottom.

Credibility and competence

It’s worth devoting time and effort to understanding the framework of rules and evidence applicable to big rig cases. Beyond the documents and rules, plaintiff counsel’s conduct in discovery shapes the case. Unique affirmative discovery will avoid boilerplate objections and cut more directly to the main issues in the case. Defense counsel will judge you by the information you possess and your willingness to obtain it, which will frequently require moving to compel further responses. Once you’re familiar with the rules and evidence you need in a trucking case, discovery is often where the case is truly won.

Dustin Thordarson

Dustin Thordarson is a trial attorney at Panish | Shea | Ravipudi LLP, whose practice focuses on serious-injury, wrongful-death and product-liability cases.

Bobby Reagan

Bobby Reagan is a trial attorney at Panish | Shea | Ravipudi LLP, whose practice focuses on cases involving catastrophic injury and wrongful death.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine