From social media to the summit

Challenging the conventional view of social media as merely a tool for impeachment, and revealing its potential as a vehicle for truth

By 2025, more than 5.6 billion people around the globe were online, and nearly 80% of American internet users actively used social media. In this hyper-connected world, platforms like Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok have become more than just digital scrapbooks of curated highlights; they are immersive, real-time diaries that record emotional and physical experiences as they unfold. For litigators, this vast digital archive is both an opportunity and a minefield.

In most personal-injury litigation, defense lawyers treat social media like buried treasure. They comb through years of posts and pictures hoping to find something – anything! – that contradicts the plaintiff’s claims of pain, disability, or loss. And all too often, they strike gold – at least in the eyes of the jury. Social media, after all, can be a potent weapon of impeachment.

But what if the social media doesn’t undermine the case? What if it tells a deeper truth?

Jack Greener was only 23 years old when he suffered a catastrophic spinal cord injury during a Brazilian Jiu Jitsu class. His recovery journey was unusually public. His social media was filled with images and videos showing him pushing physical and mental limits: rock climbing, hiking, summiting 14,000-foot peaks, mountain biking, traveling the world, living life to the fullest, and reclaiming pieces of the life he nearly lost. The LA Times covered his story. A documentary film brought it to a national audience.

Our plan? We owned it. We embraced the full arc of Jack’s digital footprint – every photo, every summit, every moment – not to downplay his injury, but to reveal its reality. His posts didn’t hide his pain; they exposed its depth. They didn’t undermine our case; they gave it weight, context, and undeniable truth.

A $46 million verdict

The result? A jury returned a $46.475 million verdict, a recovery that ultimately exceeded $56 million. It was a resounding affirmation that courage does not cancel out pain, that triumph does not erase trauma, that resilience is not the absence of suffering, that every summit has a price, and that no social media post can truly capture the depths of what a survivor endures.

This article challenges the conventional view of social media as merely a tool for impeachment and reveals its potential as a powerful vehicle for truth. Using the Jack Greener case as a framework, we explore the evolving legal standards governing the discoverability of social media evidence and share strategies for deploying it as both a sword and a shield. Through the lens of Jack’s digital footprint, which once was viewed as a potential liability, we show how it became one of the most compelling elements of his case, transforming perceived vulnerability into a powerful vehicle for victory by revealing a deeper, persuasive truth and helping pave the way to justice for a profoundly deserving client.

Legal landscape: Discoverability and admissibility of social media

As social media becomes further entwined with daily life, it has taken on a growing role in civil litigation. Courts and attorneys routinely turn to posts, photos, and messages to assess credibility, establish physical or emotional condition, and support or challenge claims of injury, intent, or bias.

Under California Code of Civil Procedure section 2017.010, social media content is discoverable if it is nonprivileged and relevant to the subject matter of the litigation. Though California case law on this issue is still developing, federal decisions provide helpful guidance.

Relevance and scope

Courts typically allow discovery of social media content when it reflects a party’s physical condition, emotional state, or social activities inconsistent with claimed injuries; however, broad or unfocused requests, such as those seeking entire accounts, all posts, photos, or metadata, are often rejected as overbroad and unduly burdensome. Discovery must be narrowly tailored by date, content type, or connection to specific claims or defenses.

Privacy and waiver

While public posts carry no reasonable expectation of privacy, private social media content may be shielded unless the requesting party can show it is relevant and proportional to the case. Courts apply a balancing test: Does the need for discovery outweigh the privacy interest at stake?

California law recognizes that privacy is not absolute. Once a party places their physical or mental condition at issue, privacy and privilege protections may be waived. (Vinson v. Superior Court (1987) 43 Cal.3d 833; Britt v. Superior Court (1978) 20 Cal.3d 844; Rosales v. Crawford & Co. (E.D. Cal. 2021) 2021 WL 4429468 (unpublished).)

Even where privacy is implicated, discovery may proceed if the material is directly relevant and essential. (Planned Parenthood Golden Gate v. Superior Court (2000) 83 Cal.App.4th 347; Williams v. Superior Court (2017) 3 Cal.5th 531.)

Federal courts have compelled private content where the request was limited and supported by a factual basis. (See, e.g., Crabtree v. Angie’s List, Inc. (S.D. Ind. 2017) 2017 WL 413242; Mailhoit v. Home Depot U.S.A., Inc. (C.D. Cal. 2012) 285 F.R.D. 566; Simply Storage Mgmt., LLC (S.D. Ind. 2010) 270 F.R.D. 430).)

In Mailhoit, the court emphasized that even private content may be discoverable, but only upon a threshold showing that the information sought is reasonably calculated to lead to admissible evidence. Courts have routinely denied “fishing expeditions” for all social media content, even in personal injury cases. (Tompkins v. Detroit Metro Airport, 278 F.R.D. 387.)

Balancing test

When privacy interests are implicated, courts apply a balancing test which weighs the need for discovery against the individual’s expectation of privacy. In personal-injury cases involving emotional distress claims, courts may permit discovery of posts reflecting mood, activity, or interpersonal relationships. Still, such discovery must be narrowly drawn. (See Vinson and Simply Storage [permitting discovery of relevant emotional content on social media but denying indiscriminate requests for all account content], supra.)

Discovery strategy and objections

Plaintiffs’ counsel must be prepared to object to vague or disproportionate demands and advocate for appropriately limited scopes. At the same time, clients must be advised that their online presence may be scrutinized, and that altering or deleting posts may trigger spoliation claims.

Admissibility challenges

Plaintiffs’ counsel should be ready to object to disproportionate demands, insist on specificity, and know where to draw the line. At the same time, it is essential to advise clients that social media may be used to challenge their injury claims, credibility, or consistency. Proactive guidance on managing their online presence is a key part of modern litigation strategy.

Even if discoverable, social media evidence may be excluded at trial unless it is authenticated and relevant. Objections may be raised under Evidence Code section 352 if the probative value is substantially outweighed by the risk of prejudice, confusion, or undue consumption of time. Motions in limine are usually the best vehicle to address these issues before the start of trial.

The injury

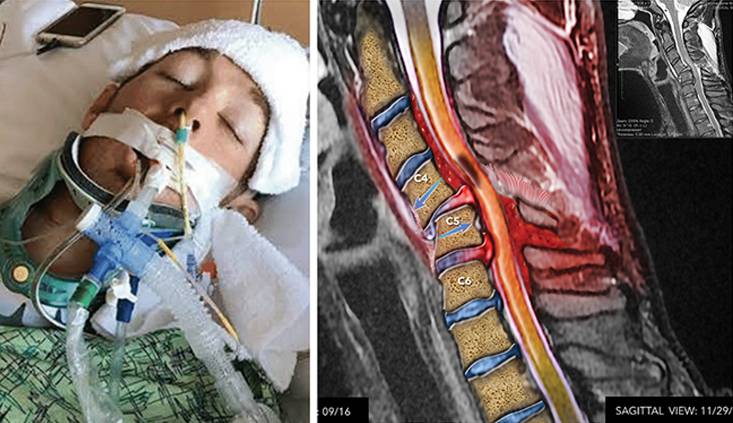

Jack Greener was a white belt in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu when his life changed forever. On November 29, 2018, during a live sparring session at Del Mar Jiu Jitsu Club, his blackbelt instructor, Francisco Iturralde, attempted a high-risk, advanced maneuver typically reserved for experienced practitioners. Jack, in the vulnerable “turtle position,” was unprepared for the forward-flip back-take. His neck snapped at C4-C5.

He was rushed to Scripps Memorial Hospital in La Jolla. His C4 and C5 vertebrae were fractured. He couldn’t move anything below his neck. Doctors told him he might never walk again. Twelve hours later, he suffered a series of strokes that nearly killed him. His diagnosis: incomplete quadriplegia.

At the time, Jack was an energetic, athletic 23-year-old who had grown up riding waves in San Diego. Just weeks away from graduating from San Diego State University, he was preparing to move to Costa Rica to become a full-time surf instructor. That future vanished in an instant.

After stabilizing, Jack was transferred to Craig Hospital in Colorado, a leading facility for spinal cord injury rehabilitation, where he began the slow, painful journey of recovery.

The recovery journey: Turning social media into a sword

From the beginning, Jack documented everything. His Instagram and YouTube videos became an unfiltered window into his world: his first thumb twitch, early rehab struggles, the halting stand, the unsteady walk, and the thousand setbacks in between. Hundreds of videos and photos documented Jack doing what most thought impossible: hiking, climbing, biking, living fully.

To the defense, Jack’s social media presence and post-injury pursuits were red flags. Evidence, they argued, of a “remarkable” recovery and an “amazing outcome.” Because Jack “could have been paralyzed for life [but] is not,” they pointed to his travel, his rock climbing, his road races, and his ability to walk, laugh, and live independently as proof that “life is not over.” In fact, they claimed Jack was “loving life,” even doing things he hadn’t done before the accident.

But rather than acknowledging his struggle, they used these images and videos to minimize it. They suggested that Jack’s story ended when he walked across the stage at graduation in May 2019 or reached the summit of Mount Whitney. They told the jury to use “common sense” to conclude that someone who can drive, date, camp, and ride a bike couldn’t possibly have suffered the kind of losses that justified the damages he sought.

But this argument fundamentally misrepresents what those posts and videos showed, as well as what they didn’t. Jack’s life wasn’t restored because he summited a mountain. His body didn’t stop hurting because he smiled for a photo. The law does not require that a plaintiff remain in a hospital bed to deserve justice.

Rather than letting the defense weaponize Jack’s posts, we reframed them. Instead of running from Jack’s story, we told it. We leaned in. Every summit, every smile, every documented step forward became part of a larger narrative, not of recovery in the traditional sense, but of fierce resilience. We showed the jury what those images didn’t reveal: the relentless work, the cost of each moment, the pain beneath the progress, the dignity of fighting for a life that would never be the same, the permanence of Jack’s injury, and the enduring toll of an injury that no photo could ever fully capture. We reframed the narrative: This wasn’t a story of recovery. It was a story of survival.

The climb: Embrace the evidence, tell the whole story

In 2021, Jack summited Mount Whitney, the tallest peak in the lower 48 states. The LA Times covered it. A documentary film – Paralyzed to Peaks – told the story to the world. The defense pointed to that summit as proof he had made a “remarkable recovery.”

Our strategy? Embrace the evidence, but tell the whole story.

The vast majority of Jack’s social media content stemmed directly from his injury and the years that followed. What the headlines and Instagram captions didn’t show, however, was the grueling journey beneath those triumphant images. We would show the jury that Jack didn’t just walk to the summit, he fought for every agonizing step.

We used the Mount Whitney climb to anchor the jury in that truth. Jack had visualized reaching that summit since the moment he left the hospital on a gurney, paralyzed from the neck down. It became his mission. For two-and-a-half years, he trained for it. From regaining the first movement, to learning to walk again, to the endless rehab and work, he visualized over and over reaching the top of Whitney. This was the motivation that kept him going.

Social media became the evidence of Jack’s willpower, not his wellness. The posts were not proof of recovery, but a record of resilience. They were part of his therapy, a way to reclaim agency over a body that had betrayed him. And we made sure the jury understood that distinction.

We showed them what it truly took for Jack to hike, to climb, to ride a bike: the countless hours of rehabilitation, the brutal setbacks, the constant fear that a single misstep could mean paralysis all over again. His posts and videos weren’t celebrations of triumph; they were survival stories. A means of staying alive, of pushing forward. These weren’t testimonials to a miraculous comeback. They were raw, unfiltered glimpses into the reality of his daily struggle and the truth behind the curated posts.

An image can show a moment. A voice can tell its story. By combining the two, we transformed images on a screen into a story the jury could feel.

Using witnesses to reframe the narrative

One of the most powerful storytellers was Justin Weiner, the ICU nurse who first encountered Jack in his most vulnerable hours. At trial, Weiner recounted seeing Jack motionless and terrified in the ICU at Scripps Memorial Hospital. On Jack’s first night, he sensed something was wrong and told Weiner, “I think I’m going to die.” Moments later, as Weiner was calmly assuring Jack that he wasn’t going to die, Jack lost consciousness. The strokes came fast. His odds of survival were slim.

What left the greatest impression wasn’t just Jack’s physical condition; rather, it was his mindset. Weiner described how Jack made a vow: “I’m going to walk out of here.” He told us about how Jack’s vow to walk again seemed medically impossible, but emotionally undeniable.

Jack fought his way through weeks of intensive care, then months of rehab in Colorado, staying in touch with the nurse who once sat by his bed. A year later, they reunited in a bar in Encinitas. Jack didn’t roll in. He walked through the door. Justin was “absolutely floored.” When Jack revealed his goal of summiting Mt. Whitney, Weiner, an ultramarathon runner, didn’t hesitate. He joined the expedition and began training with Jack. What followed was a reality check.

Weiner testified that he had “definitely overestimated Jack’s abilities.” He described seeing Jack manually lift his legs with his arms, and how he often had to physically push Jack from behind. On a training trip to Big Pine, a 14-mile hike over three days, he saw firsthand how Jack’s body struggled to adapt. Jack battled drop foot. He relied on walking sticks. He required catheterization to urinate. His nervous system couldn’t regulate heat like others. And the fear was constant.

When Jack finally attempted to climb Whitney, a trek of over 37 miles across five days with nearly 9,000 feet of elevation gain, Weiner described a grueling, often terrifying journey. Jack moved at less than a mile per hour, dragging his foot through rocky terrain and soft sand. His legs trembled with every step. He fell so frequently that they assigned a spotter to walk behind him at all times. Friends carried all the supplies so Jack could focus on walking. When he stumbled, he couldn’t catch himself, as his brain’s delayed signals made that impossible. On narrow ridgelines with 30-foot drop-offs, Weiner held onto Jack’s shirt to keep him safe.

At one point, exhausted and trembling, Jack asked the same question he’d asked in the ICU: “Am I going to die today?” And Weiner gave him the same answer: “You’re not going to die.” Then he helped him keep moving forward.

When Jack finally reached the peak, he broke down in tears.

His testimony told the jury what no social media could: the price of that moment. The physical toll. The pain behind the perseverance. The fear behind the smile.

Jack didn’t climb Mount Whitney in spite of his injuries. He climbed it because of them.

Jack testified over two days. He was composed, candid, and deeply human. He didn’t sugarcoat his story. He spoke about crying from pain in the mornings. About collapsing after hikes. About cracking his head open during falls, and the pink tape friends used to patch him up. About the constant calculations he must make just to walk across a room.

Jack’s parents added their own truths. His mother spoke about the fear that gripped their lives, the panic attacks, sleepless nights, the long drives to the hospital, the falls, the fear etched into every day, and the trauma no post ever captured. His father shared what it means to watch your child live on the edge of another catastrophe, knowing a fall or misstep could bring it all crashing down again.

Cross-examining the defense narrative

The defense’s opening and closing arguments painted Jack as someone who had made a “truly amazing” recovery. But their narrative relied on fragments, selective images meant to obscure the cost of what Jack achieved.

We used those same images, but contextualized them. We showed what the camera didn’t: the tremors, the leg drag, the medications, the surgeries. We walked the jury through the reality that recovery does not mean return. Jack would never return to who he was before that November day.

The defense tried to use Jack’s public persona against him. They showed a photo he had posted on social media of Jack balancing on a tightrope, arms outstretched. Their claim? Not just that he was fine, but that he was thriving. That Jack’s performance demonstrated exceptional physical ability and signaled a remarkable recovery.

But we introduced the full video, which told a different story. The jury watched as Jack inched along that rope, flanked by two friends whose arms had been cropped out of the picture. They saw his face twist in concentration. They saw the struggle. They saw the fear. That moment became a metaphor for the entire case: the defense showed the image. We showed the reality.

We juxtaposed Jack’s social-media posts with expert medical testimony, including not only retained experts but also his treating physicians, to complete the narrative, reinforce its credibility, and close the loop.

Dr. Kevin Yoo, the neurosurgeon who treated Jack and performed his spinal surgery at Scripps, explained the medical science behind Jack’s injuries. He testified that Jack’s neurological damage was permanent. While Jack’s progress in regaining mobility was exceptional, Dr. Yoo emphasized that it was incomplete and always would be.

Dr. James Fontaine, a board-certified physiatrist who treated Jack primarily for hormone replacement therapy, reinforced the permanence of Jack’s condition from a clinical perspective. He testified that Jack was living with central cord syndrome, a diagnosis that would affect him for the rest of his life. Dr. Fontaine described the permanent nerve damage, the ongoing need for pain management, and the critical importance of lifelong medical monitoring.

The message was clear: this was not recovery. This was survival.

What we fought to keep out – and why it mattered

Embracing social media as part of your trial strategy does not mean abandoning caution. You have to know where to draw the line. In Jack’s case, we were deliberate about what belonged in front of the jury and what didn’t. While we welcomed the opportunity to show the reality of his struggle, we were equally committed to ensuring that social media would not be twisted or misused. That meant taking proactive steps to exclude irrelevant and prejudicial content that had no bearing on the injury at issue.

The defense sought to introduce video footage of Jack participating in Brazilian Jiu Jitsu competitions before his injury. Their argument: Jack was not a true beginner, and the risks he faced during the incident were less severe than portrayed. They also attempted to introduce footage of Jack wrestling in high school, material that was even further removed from the facts of the case.

We responded with targeted motions in limine to exclude this content. The footage did not depict the maneuver that caused Jack’s injury. It did not reflect the conditions under which the injury occurred. Jack was injured during a low-stakes, in-class sparring session between a white belt student and a black belt instructor; he was not in a competitive match between evenly matched opponents. The photographs and videos showed a different environment entirely, with different stakes, different techniques, and a different level of supervision and control.

Allowing that footage into evidence would have confused the issues, misled the jury, and created unfair prejudice. The court agreed. The judge excluded the footage, finding it cumulative, confusing, and lacking probative value. That evidentiary ruling later became one of the central issues on appeal, but the court of appeal affirmed it in full.

This was a critical win. It ensured that the jury focused on what mattered: how Jack was injured, why it happened, and what it cost him. It protected the integrity of the trial and shielded the truth from distortion.

The verdict: Truth in full color

The jury saw Jack. They saw a man who defied the odds not because he wasn’t hurt, but because he was. They heard from friends, family, doctors, and Jack himself. They saw the Instagram photos and the YouTube clips, but more importantly, they saw everything around them.

They saw the humanity, the pain, the truth. Social media didn’t tell the whole story. But we did.

And they returned a verdict of $46.475 million.

Lessons learned: Reframing social media in litigation

This case is a blueprint for rethinking how social media can be used in personal-injury litigation. While plaintiffs’ lawyers are rightly cautious about a client’s online presence, there are situations where embracing that evidence, honestly and strategically, can bolster the damages case.

Key takeaways:

Own the narrative: Don’t let the defense tell your client’s story for you. Use social media to provide a full, honest picture.

Context is everything: Videos and photos lack context. Fill in the gaps with testimony, medical evidence, and personal narratives.

Witnesses matter: Surround social media evidence with credible witnesses who can explain what it doesn’t show.

Credibility wins: Jack’s authenticity on the stand made his story real. Social media didn’t undercut his credibility; it amplified it.

Best practices: Managing the social-media minefield with a proactive strategy

Social media is a double-edged sword. If not properly vetted and managed from day one, it can easily be exploited by the defense to undermine a plaintiff’s credibility and diminish the value of their claims.

Defense counsel and insurers routinely scour plaintiffs’ online activity and publicly available content, including photos, comments, check-ins, and tags. Posts can be taken out of context or used to paint an incomplete picture of the plaintiff’s physical or emotional condition. Early guidance helps ensure that social media activity supports, rather than distracts from, the case.

A thoughtful social-media strategy is now a routine and necessary part of modern litigation.

Set expectations from day one

At the initial intake, counsel should advise clients to:

Set all accounts to private;

Avoid posting about their injury, lawsuit, recovery, or day-to-day activities;

Preserve existing content to avoid claims of spoliation; and

Assume that any public activity may be reviewed by the other side.

This isn’t just about concealing information. Instead, it’s about protecting the integrity of the case and helping the jury focus on the complete and accurate story.

Use a written social-media protocol

In addition to verbal guidance, provide clients with a written advisory that covers:

How even private posts can be discovered and misinterpreted;

Lesser-known platforms like Strava, Venmo, and shared calendars;

Clear restrictions on posting or referencing the case; and

Information to share with family and friends to avoid well-meaning but problematic posts.

A simple comment like, “You look great!” or a shared photo at a social gathering can be misrepresented to suggest the plaintiff is uninjured. Defense attorneys are adept at assembling narratives from fragmented digital evidence across multiple accounts.

In today’s litigation landscape, a well-crafted social media strategy is now essential trial practice. When proactively managed, it not only shields your client from misinterpretation but can also serve as a compelling piece of the case narrative and a powerful asset.

Social media may be a minefield, but with planning and perspective, it can also become a map.

Conclusion

Jack Greener is not the man he was before his injury. But neither is he the man the defense tried to portray. He is someone who fought – is still fighting every day – to reclaim pieces of his life, knowing full well that others will only see the end of the trail, not the climb.

By embracing the very evidence the defense thought would destroy our case, we gave the jury a view from the summit, not to show that Jack had no injuries, but to show just how far he had to climb to rise above them.

Rahul Ravipudi

Rahul Ravipudi is a partner at Panish Shea Boyle Ravipudi and has spent his legal career handling catastrophic injury and wrongful death cases. Mr. Ravipudi has served as an adjunct professor teaching Trial Advocacy at Loyola Law School since 2008. He can be reached at ravipudi@psblaw.com.

John Shaller

John Shaller is a trial attorney at Panish | Shea | Boyle | Ravipudi LLP, whose practice focuses on litigating catastrophic personal injury and wrongful death cases. He earned his undergraduate degree from Southern Methodist University and his law degree from University of La Verne College of Law. He is licensed to practice before all courts in the State of California.

Paul A. Traina

Paul A. Traina of Engstrom, Lipscomb & Lack specializes in complex civil/business litigation, class action lawsuits, securities litigation, and professional liability claims. A 1991 graduate of Pepperdine University School of Law, he was named one of Southern California’s Super Lawyers, 2004-2008 and served as the Consumer Attorneys of California, 2002-2003.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine