Pretrial settlements and their impact on your verdict

Calculating and reducing setoffs in personal-injury and medical-malpractice cases

Math is hard. That’s why many of us decided to become lawyers. But when partially resolving a case involving more than one defendant, it is critical to understand the impact of that settlement toward any potential verdict.

It is also important when dealing with insurance claims representatives and defense attorneys. It is shocking how many defense attorneys just blindly believe that there is a dollar-for- dollar setoff when it comes to prior settlements. Under Code of Civil Procedure section 877, subdivision (a), a settlement with one defendant prior to trial “shall reduce against the others in the amount stipulated by the release…” However, because each defendant is only severally liable for their proportionate share of noneconomic damages according to fault under Civil Code section 1431.2, subdivision (a), there is not a dollar-for-dollar setoff settle reduction.

When negotiating with such attorneys and claims representatives, the plaintiff’s attorney must be able to articulate that only a portion of a prior settlement is offset. Perhaps most importantly, you must understand the law to craft that settlement agreement as to reduce the potential offset of any such settlement.

Here is a public calculator that we drafted to help you calculate the impact of any pretrial settlement towards a potential judgment: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1akDNn-fOimZnB00p8uGkB-6iV3EHLJWJse-5ebm049s/edit?usp=sharing.

Let’s do the math: Calculating the pretrial settlement with one of the defendants

The vast majority of settlements in cases involving more than one defendant occur before trial. Fortunately, calculating the offsets of such settlements is relatively easy.

Under the holding of Espinoza v. Machonga (1992) 9 Cal.App.4th 268, a court simply calculates the percentage of the overall damages award that consists of economic damages, multiplies the settlement proceeds by that percentage, and reduces the economic-damages award by the resulting amount.

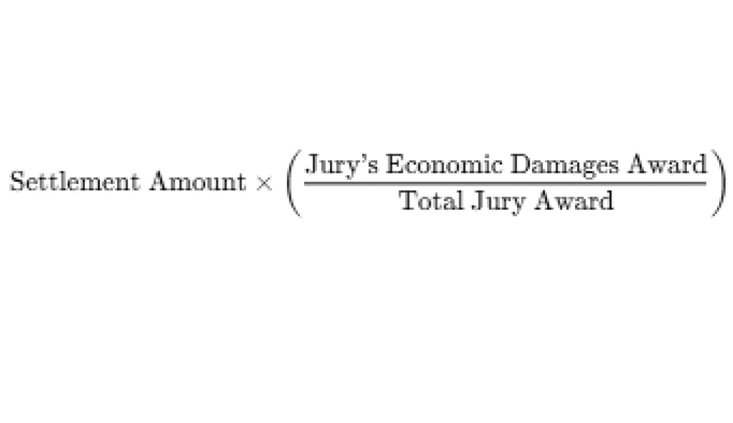

In other words, the offset is simply the following (Fig.1):

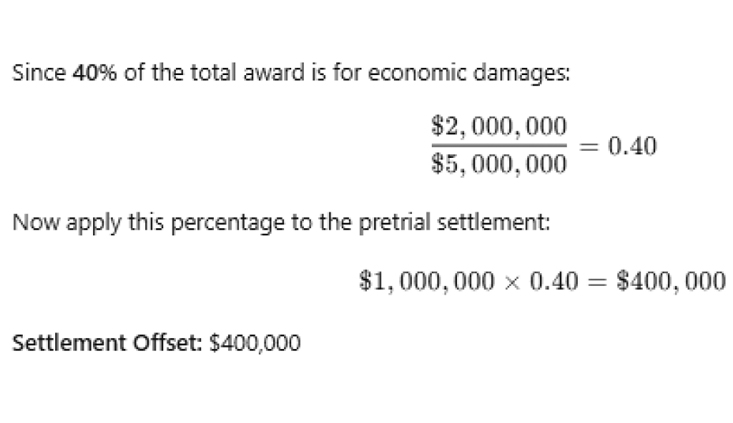

For example, let’s say that there are two defendants at fault for a plaintiff’s injuries. Defendant A settles the case for $1,000,000 before trial. At trial against Defendant B, the jury finds for the plaintiff in the amount of $5,000,000, with $2,000,000 in economic damages and $3,000,000 in noneconomic damages. The jury also finds Defendant B 60% at fault, Defendant A 30% at fault, and the plaintiff 10% at fault. What is the offset?

Since 40% of the jury’s verdict comprised of economic damages, only 40% of the $1,000,000 pretrial settlement is offset. Thus, $400,000 is reduced from the jury’s verdict based on the $1,000,000 pretrial settlement.

Step 1: Calculate the Settlement Offset

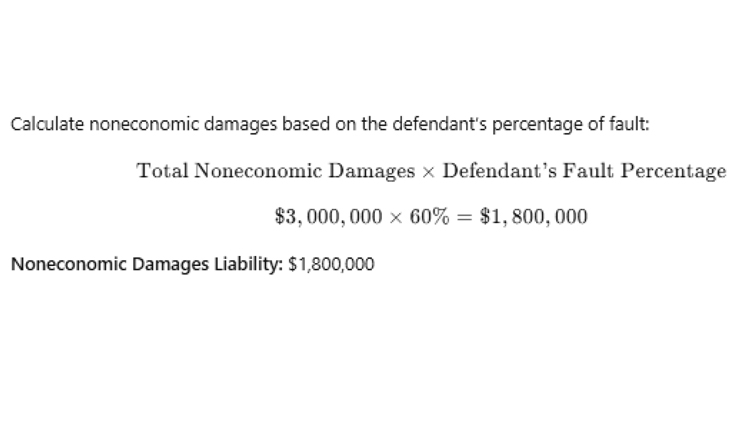

The next step is to simply apply prop 51. Proposition 51, which is codified at Civil Code section 1431.2, states that a defendant is only liable for their proportionate share of fault as to noneconomic damages (Fig. 2).

Step 2: Calculate Noneconomic Damages (Prop 51)

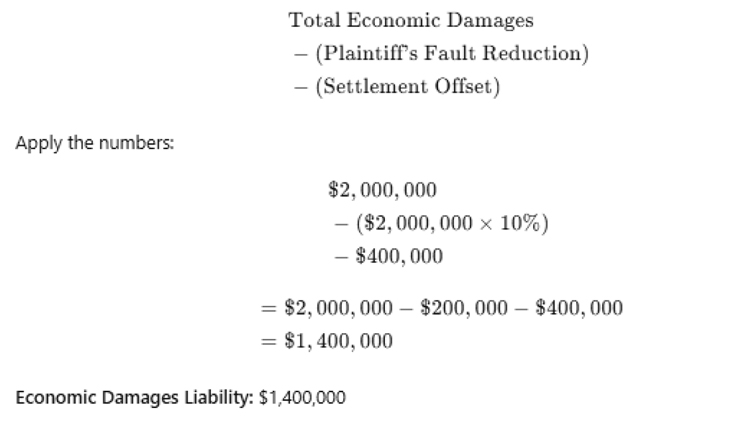

Unlike noneconomic damages, economic damages are subject to joint-and-several liability. But such damages must be reduced by the plaintiff’s comparative fault and any applicable settlement offset (Fig. 3).

Step 3: Calculate Economic Damages (with Comparative Fault and Settlement Offset)

Finally, simply add the numbers together to get the final adjusted judgment (Fig. 4):

Step 4: Calculate Total Judgment Against Defendant B

Since the basis for this formula is Espinoza v. Machonga, calculating such an offset is now widely known as applying the “Espinoza method.” (Fig. 5)

In Espinoza, a door shattered and glass fragments struck the plaintiff’s eye. The housing authority defendant settled for $5,000, which was approved in a good-faith finding. Against the remaining individual defendant, the matter went to arbitration. The arbitrator awarded $6,242.94 in economic damages and $15,000 for general damages. The arbitrator also found the plaintiff 10% at fault, the individual defendant 45% at fault, and the settling housing authority 45% at fault. The parties agreed that the court would determine the amount of the offset.

Both the trial court and the appellate court applied the rule now known as the Espinoza method. Since 29% of the award was for economic damages, $1,467.77 (29% of the $5,000) was offset. For plaintiff’s comparative fault, $624.29 (10% of the $6,242.94) was reduced. Thus, the defendant was liable for $4,150.88 of economic damages ($6,000-$1,467.77-$624.29) and $6,750 in general damages (45% of $15,000). The judgment thus totaled $10,900.80.

Espinoza addressed the interplay between Code of Civil Procedure section 877 and Prop 51 at length. Section 877 was already in place when Prop 51 was passed in 1986. Since Prop 51 already decreased a plaintiff’s noneconomic damages due to several liability only, to reduce the entire amount of a prior settlement would be double-penalizing a plaintiff.

Notably, even if a jury ultimately finds that a settling defendant was not at fault at trial, that does not impact the amount of the setoff. In Poire v. C.L. Peck/Jones Brothers Construction Corp. (1995) 39 Cal.App.4th 1832, 1839, the jury determined that two defendants who settled before the verdict were not at fault, and the trial court declined to apply any setoff for those settlements. The Court of Appeal reversed, reasoning that section 877 requires a setoff for pre-verdict settlement amounts paid by any “tortfeasors claimed to be liable for the same tort without regard to their actual liability.” As a result, the Espinoza method was still applicable to pre-verdict settlements reached with the defendants who were eventually found not liable.

It is doubtful that a party could bypass the Espinoza method by allocating different amounts in a settlement agreement

The settling parties typically cannot bypass the Espinoza method by allocating between economic and noneconomic damages in a settlement agreement. Absent unusual facts, such an allocation does not impact the amount of a setoff.

The setoffs under Code of Civil Procedure section 877 apply when the acts of multiple defendants combined to cause one injury. Thus, allowing the parties to allocate between economic and noneconomic damages “would necessarily infringe on the factfinding power of the jury.” (Greathouse v. Amcord, Inc. (1995) 35 Cal.App.4th 831, 841.)

Of course, it is advantageous for the plaintiff that a prior settlement be determined to be mostly noneconomic in nature to reduce the potential setoff. By contrast, a settling defendant has no incentive to oppose a plaintiff’s allocation as it is unaffected. Thus, as explained by Greathouse, “the allocation of the settlement proceeds according to the proportions recited in a pretrial settlement agreement is inherently suspect.”

In Greathouse, a surviving wife and her five children filed suit based on her husband’s asbestos-related disease. They settled for $284,000 against multiple defendants, and in the agreements, allocated 80% of the amounts towards noneconomic damages. At trial against the remaining cement company, the jury found the company 2% at fault and awarded $289,174.10 in economic damages and only $100,000 in noneconomic damages. The trial court set off only 20%, or $56,800, of the $284,000.

The Court of Appeal reversed, finding that since 74.3% of the verdict was economic damages, that 74.3% of the prior $284,000 settlement (or $211,026), should have been offset. (See also Erreca’s v. Superior Court (1993) 19 Cal.App.4th 1475, 1481 [holding that the trial court erred in deviating from the Espinoza method even when the plaintiff died during trial, impacting the jury’s verdict for noneconomic claims].)

Somewhat surprisingly, it is unresolved whether a trial court’s allocation at a good-faith hearing pursuant to Code of Civil Procedure section 877.6 hearing could supersede the jury’s allocation. Of course, trial courts can (and almost always do) approve settlements without a specific allocation towards economic and noneconomic damages. (Dole Food Co., Inc. v. Superior Court (2015) 242 Cal.App.4th 894, 918.) In addition, dicta in Espinoza and Greathouse suggest that even allocation approvals at an 877.6 hearing would not replace the outcome of the Espinoza method.

A plaintiff may still be able to reduce offsets by allocating amounts to different claims

Critically, however, a plaintiff may be able to significantly reduce the amount of the offset by allocating amounts to different claims. As long as it passes “the smell test” and there is a clear benefit to the settling party, such allocations may be found to be valid.

The strongest claim to allocate funds to, if the facts warrant it, is the future wrongful-death claim. However, the injuries must be so severe that death is a realistic possibility. As long as the plaintiff produces evidence of a close relationship between the plaintiff and his heirs, those amounts allocated to the future wrongful-death claim may be reduced from the settlement amounts for the offset calculation. However, allocation to other claims or elements of damages (such as attorney fees in an elder-abuse action) may also help avoid setoff amounts.

In short, “Courts have wide discretion in allocating prior settlement recoveries to claims not adjudicated at trial.” (Pfeifer v. John Crane, Inc. (2013) 220 Cal.App.4th 1270, 1321.) The burden is on the plaintiff to show that the allocation is reasonable. (Ibid.)

In Wilson v. John Crane, Inc. (2000) 81 Cal.App.4th 847, 850, the plaintiff was suffering from mesothelioma caused by industrial exposure to asbestos. Before trial, the plaintiff settled against several defendants for $1,165,802. As part of those settlements, the parties agreed to allocate 60% ($699,481) to the personal-injury claims, 20% ($233,160) to the waiver of a future wrongful death claim, and 20% ($233,160) to the loss-of-consortium claim. The heirs to the wrongful-death claim did not even sign the settlement agreement. Rather, the wife waived her own claim for wrongful death and the plaintiffs both signed a hold-harmless agreement for future wrongful-death claims brought by their children.

Against the remaining manufacturer defendant, the jury returned a verdict, finding the defendant 2.5% at fault and awarding $590,000 in economic damages, $3,000,000 for pain and suffering, and $1,000,000 to the plaintiff’s wife for loss of consortium. Thus, under Prop 51, the pain-and-suffering damages were reduced to $75,000 to the plaintiff and $25,000 to his wife.

The trial court included both the wife’s loss-of-consortium claim and the plaintiff’s noneconomic damages claims in calculating the Espinoza formula, resulting in an economic/total damage ratio of the jury verdict of 13%. The court then multiplied the 13% by the $699,481 settlement attributable only to the plaintiff’s own claims, resulting in an offset of only $90,932. On appeal, the defendant argued that the trial court erred in not including the wrongful-death damages or the damages for loss of consortium.

As for the future wrongful-death damages, the Court of Appeal affirmed. The Court explained that such damages could not possibly be subject to offset since there was no jury verdict that awarded such damages. Since a wrongful-death claim is a distinct and independent claim from personal-injury damages, settlement of such claims should not be considered for the purposes of offset. Thus, “sums properly allocated to wrongful-death claims cannot be automatically applied to a personal-injury judgment in favor of the prospective decedent.”

The Court of Appeal came to a similar result as to the loss-of-consortium claim. First, the court explained that the trial court erred in considering the $1,000,000 awarded to the wife as part of the Espinoza formula. Since the wife’s claims are independent and distinct from the plaintiff’s claims, the Espinoza formula should have only been the plaintiff’s economic/total damage ratio, or 16%. In short, “all damages for loss of consortium should have been excluded entirely from the Espinoza calculus. This applies both to amounts awarded by the jury, which should have been excluded in calculating the ratio of economic to noneconomic damages, and to amounts properly allocated to loss of consortium in settlement.”

Thus, in Wilson, “[w]e conclude that sums properly allocated to loss of consortium in the settlements were, like sums properly allocated to potential wrongful death claims, properly excluded from the calculation of settlement credits.”

A similar result occurred in Hackett v. John Crane, Inc. (2002) 98 Cal.App.4th 1233, another mesothelioma case. There, the parties agreed that 34% of a $4.6 million pretrial settlement would be allocated to the future wrongful death claims and 15% to the loss-of-consortium claim. The children did not sign the settlement agreement, but the plaintiff and his wife entered into a hold-harmless agreement.

After a seven-figure jury verdict, the Court of Appeal affirmed the trial court’s decision to exclude these amounts from the offset calculus. Notably, the trial court noted that the plaintiff was a kind and attentive father with a close relationship with his wife and adult sons. Moreover, the settling defendants were receiving a benefit: “The agreements make it clear that the settling defendants believed and expected there would be no future claims by the heirs.”

That being said, despite claiming it was following Wilson, the Hackett court came to a different result regarding the loss-of-consortium claims. It included those claims in the Espinoza proportional calculus as well as the amount of the prior settlement, finding that the jury verdict must supersede any allocation by the parties. While such a calculation assisted the plaintiff in this particular case, a low loss-of-consortium jury verdict in other cases could negatively impact that calculation.

Unfortunately, the court came to an opposite result in Jones v. John Crane, Inc. (2005) 132 Cal.App.4th 990, 996. In Jones, the plaintiff sued for lung cancer due to exposure to asbestos. He settled the cases against a handful of defendants for around $1.5 million. The plaintiff tried to follow the Wilson example by allocating 20% to the wrongful-death claim and 20% to the loss-of-consortium claim.

Against the remaining manufacturer, the jury found about 2% fault. The jury found economic damages to be just over $1 million, noneconomic damages to be $3.5 million, and loss-of-consortium damages to his wife of $500,000. The trial court rejected the settling parties’ allocation of the settlement and applied the Espinoza formula to the entire settlement.

The Court of Appeal affirmed. Following Hackett, the court found that the jury’s verdict controlled as to the loss-of- consortium damages. Thus, they could not be excluded from the Espinoza method.

As for wrongful death, the Court of Appeal held that the trial court did not abuse its discretion in rejecting the 20% allocation to wrongful death. Notably, the trial court noted that there was no evidence regarding the family or the relationship between the plaintiff and his heirs. The Court of Appeal explained that “[t]he party seeking to rely on the allocation must explain to the court and to all other parties, by declaration or other written form, the evidentiary basis for any allocations and valuations made, and must demonstrate that the allocation was reached in a sufficiently adversarial manner to justify the presumption that a reasonable valuation was reached.”

Since there was absolutely no evidence or information regarding even the number of heirs or their relationship with the defendant, the 20% allocation to wrongful death was properly rejected. (See also Pfeifer v. John Crane, Inc. (2013) 220 Cal.App.4th 1270, 1322 [finding that the trial court properly rejected a 50% allocation to future wrongful death claims because there was “no showing regarding [the plaintiff’s] relationships with his offspring, for purposes of determining the value of their claims”].)

There are no special rules in medical-malpractice actions

Previously, there were cases involving medical malpractice that held that the jury’s verdict was first adjusted by MICRA’s Civil Code section 3333.2 cap in determining the Espinoza calculation. This would often be devastating. For example, in Mayes v. Bryan (2006) 139 Cal.App.4th 1075, even though the jury awarded $3 million in noneconomic damages and $1.4 million in economic damages, the Court of Appeal held it was proper to reduce the $3 million to the old cap of $250,000 before applying the Espinoza formula. Thus, the court further reduced the judgment (which was already crippled by MICRA) by 85% instead of 32% in relation to a prior $650,000 settlement.

Fortunately, in the recent case of Collins v. County of San Diego (2021) 60 Cal.App.5th 1035, the Court of Appeal refused to first reduce the noneconomic damages under MICRA before determining the percentage of damage the jury allocated to noneconomic damages. Collins explained that eight years after the Mayes decision, the California Supreme Court held in Rashidi v. Moser (2014) 60 Cal.4th 718, 727, that the MICRA cap applies only to judgments awarding noneconomic damages and not settlements. In determining the cap should not be applied to settlements, the Court set forth its rationale that if non-settling defendants were assured an offset of noneconomic damages regardless of their degree of fault, an agreement with one defendant would diminish the incentive for others to settle. It held that no MICRA provision, and no other statute, authorizes a posttrial reduction in the amount of a settlement.

Thus, in medical-malpractice cases, there are no special rules. Just as in any other civil cases, the offset calculation is based on the unadjusted jury verdict of economic damages divided by total damages.

There are different rules for post-verdict settlements

Just when the math could not get any more complicated, there is yet another method of calculating offsets when a settling defendant resolves the case after the jury returns its verdict. In such cases, instead of the Espinoza method, courts must use the “Ceiling Approach” as established in Torres v. Xomox Corp. (1996) 49 Cal.App.4th 1.

In Torres, a maintenance worker died from horrific burns he suffered while at work. A jury found the company that sold a defective valve 10% at fault. The jury also found the manufacturer of the valve 5% at fault. The jury awarded just over $2 million in damages, of which about $1.1 million (55%) were economic damages and around $900,000 were noneconomic damages.

The company that sold the valve and was found to be 10% at fault, settled its case for $450,000. Applying the Espinoza method and multiplying $450,000 by 55%, $250,000 would be offset as economic damages. The problem is that under this scenario, the $200,000 remaining exceeds any potential liability for general damages for the defendant seller. Since the seller was 10% at fault, his maximum exposure for noneconomic damages was only $90,000.

The Court of Appeal held that “no more of the settlement could properly be allocated to non-economic damages than [the] post-verdict liability for those damages.” This is because, unlike with pre-trial settlements, the settling defendant’s actual liability is known. Thus, as explained by the Torres court: “We conclude that the Espinoza approach is not a suitable means of apportioning a post-verdict settlement because it may result in an allocation of more of the settlement to non-economic damages than the settling defendant’s liability for such damages under the verdict.”

Instead, the “Ceiling Approach” must be used. In this method, the settlement is first allocated to non-economic damages up to the amount of the settling defendant’s liability for such damages. In the Torres case, since the maximum possible liability of the seller defendant was $90,000, the remaining amount ($360,000 of the $450,000) should have been apportioned to economic damages and thus offset.

The ceiling approach will always leave a plaintiff either equal or worse off than with the Espinoza method. Thus, if a plaintiff is negotiating during jury deliberations with one of multiple defendants, it is important that any settlement is finalized with the terms reported to the court before the jury returns with the verdict. For example, in Hellam v. Crane Co. (2015) 239 Cal.App.4th 851, 870, the plaintiff and the settling defendant agreed on a settlement amount long before the jury verdict. However, the jury returned its verdict while the settling parties were still negotiating terms of the release language. Under this scenario, the Court of Appeal held that the trial court erred in using the Espinoza method rather than the ceiling approach, resulting in a larger setoff.

Benjamin Ikuta

Benjamin T. Ikuta is the founding partner at Ikuta Hemesath LLP in Santa Ana, where he concentrates his practice entirely on medical malpractice on the plaintiff side. Ben can be reached at ben@ih-llp.com.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine