Settlement agreements in employment cases

On the road to settlement, negotiate non-monetary terms before you agree to a number

“Congratulations, counsel. You have a deal,” the mediator tells you. You look at the clock and see that it’s midnight. You and your client have been on Zoom since 10:00 a.m. You are exhausted, but relieved that everyone accepted the mediator’s proposal. “Now,” says the mediator, “defense counsel has prepared a settlement agreement and is emailing it over to you. No one leaves until it’s signed.”

Your heart sinks. Your email pings. You open up the settlement agreement that defense counsel has sent. As your bleary eyes scan the agreement, you see that it contains several objectionable provisions. You think, “Wouldn’t it be nice if someone had recently written an Advocate article on this topic?”

Negotiate non-monetary terms in advance

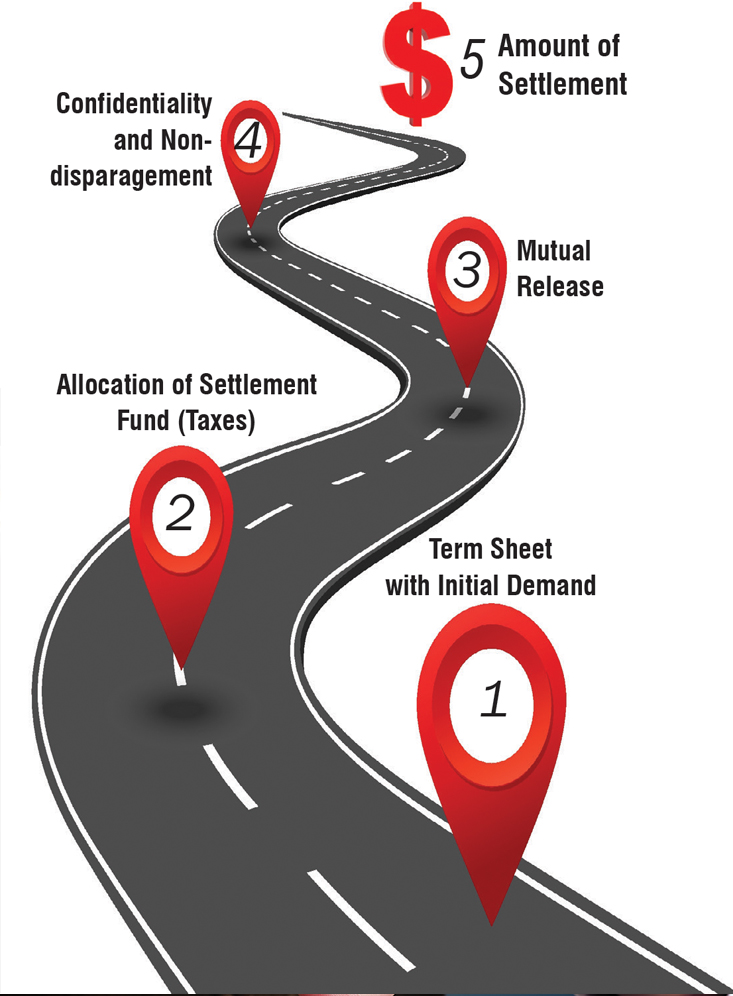

If there is one thing you should take away from this article, it is this: Negotiate important non-monetary terms before agreeing on the money. Once you agree to a monetary amount, your leverage all but disappears.

Many mediators discourage plaintiffs from trying to negotiate non-monetary terms at the same time (or before) monetary terms. They say: We want to “get to yes” on a dollar amount, and we do not want to jeopardize the chances of settlement by getting distracted with non-monetary terms. While this argument has some level of appeal, keep in mind that your client’s interests and the mediator’s interests are not the same. The mediator wants to get a deal done, even if it includes an onerous liquidated damages provision or unlawful non-disparagement clause. Your client also wants to get a deal done, but is relying on you to ensure that the deal does not contain any provisions that are going to come back to haunt the client later.

Your best chance of protecting your client’s interests is to negotiate non-monetary terms in advance. Consider preparing a term sheet of non-monetary terms before attending the mediation. If you are negotiating directly with defense counsel, consider sending the term sheet simultaneously with your first monetary demand, and insisting that non-monetary terms be agreed to before landing on a number. Explain to defense counsel that you do not want to waste valuable time at the mediation arguing over non-monetary terms. Negotiating non-monetary terms in advance is a simple practice pointer that will save you from having to argue with defense counsel about those bad settlement terms they routinely propose – often at midnight when there is a big incentive for you to cave so everyone can get some sleep.

Allocating the settlement payment

“I am not a tax attorney and I cannot give you tax advice.” Although this is a standard refrain for many employment lawyers, it is nevertheless important for us to have a general understanding of the taxability of settlement proceeds so we can advocate for allocations that are defensible and may minimize the client’s tax burden. The IRS has provided helpful guidance stating that, generally speaking, “the IRS will not disturb an allocation if it is consistent with the substance of the settled claims.” (See https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p4345.pdf)

There are typically four potential buckets for the allocation of settlement proceeds in employment cases: 1) wages, 2) damages for physical injuries, including emotional distress, 3) non-wage damages that are not based on physical injuries, and 4) attorneys’ fees.

First, with respect to settlement proceeds characterized as wages, the IRS tells us (not surprisingly) that they must be reported to the taxing authorities on a W-2 Form, and are subject to employment taxes, such as income, social security and Medicare taxes. (Ibid.)

Second, the IRS tells us that settlement proceeds allocated to physical injuries, or emotional distress resulting from physical injuries, are typically not taxable. (Ibid.; see also 26 U.S.C. § 104 (a)(2).) This means that if your case involves a physical touching, such as a sexual assault or workplace fistfight, it might be worth exploring whether to allocate some of the settlement to the physical injury claims. The client will ultimately need to work with her tax advisor to decide whether the proceeds are taxable, but the allocation in the settlement agreement could provide a helpful way for the client to minimize her tax burden.

Third, you may choose to allocate some portion of the settlement to non-wage damages that are not based on physical injuries, such as damages for emotional distress or defamation. While the IRS tells us that these types of damages are reportable as taxable income, they are not subject to employment taxes, unlike wages. (See https://www.irs.gov/government-entities/tax-implications-of-settlements-and-judgments) Accordingly, even without a physical injury, it may be worthwhile to allocate some portion of the settlement proceeds to these types of non-wage damages – so long as such an allocation would be supported by the allegations of your lawsuit. If your lawsuit solely alleges unpaid wage claims under the Labor Code, it may not be supportable to allocate 100% of the settlement to non-wages.

Fourth, plaintiffs in many types of employment cases are generally permitted to take an above-the-line deduction for attorneys’ fees. (See Robert W. Wood, New Tax on Litigation Settlements, No Deduction for Legal Fees (Dec. 4, 2019) available at https://marinbar.org/news/article/?type=news&id=500.) For this reason, it may be a good idea to state in the settlement agreement the amount that is being allocated to attorneys’ fees.

The allocation of settlement proceeds is something you should explore with your client before you begin settlement negotiations. This will provide them with ample time to consult with a CPA or tax attorney, and for you to be prepared in advance to propose a defensible allocation that tracks the allegations of the lawsuit.

Limit indemnification for tax consequences

Employers often include provisions in settlement agreements requiring the employee to indemnify them for all manner of things if they get nailed by the taxing authorities as a result of the settlement allocation. While it may be difficult to convince defense counsel to remove the indemnification provision altogether – they often counter such a request by insisting that the entire settlement be allocated to wages – you should push as hard as possible to limit the indemnification provision to any failure by the employee only to pay proper taxes.

Do not agree to indemnify the employer for its own failure to pay the employer’s share of taxes. Again, if you negotiate non-monetary terms in advance, you will have the leverage to say “no” to indemnification. If you already have a deal on the money, it will be much harder to insist on no indemnification, especially if your client is the one pushing for high non-wage allocations.

The release should be mutual

Employers often include releases that require only the employee to give up her claims, without any requirement that the employer do the same. Insist that the release be mutual. Explain that you want finality between the parties. A mutual release will give your client peace of mind. (And, true story, a mutual release will protect your client just in case the employer later discovers that the client submitted fake reimbursement reports, or whatever.) Defendants will often agree without too much of a fight. The mutual release should encompass both known and unknown claims.

Confidentiality and non-disparagement provisions

The California Legislature recently passed several new laws limiting the use of non-disparagement and confidentiality provisions (also called non-disclosure agreements, or “NDAs”) in certain employment cases. This is good news, but the patchwork of laws has generated lots of confusion about what is permissible. As of January 1, 2022, there are three California statutory sections governing confidentiality and non-disparagement provisions that all employment attorneys should know.

First, there is a revised section of the Fair Employment and Housing Act (“FEHA”) that prohibits employers from including in a severance agreement any provision that prohibits the disclosure of information about unlawful acts in the workplace. (Gov. Code, § 12964.5, subd. (b)(1)(A).) If the employer wishes to include a non-disparagement provision in a severance agreement, it must include the following language: “Nothing in this agreement prevents you from discussing or disclosing information about unlawful acts in the workplace, such as harassment or discrimination or any other conduct that you have reason to believe is unlawful.” (Gov. Code, § 12964.5, subd. (b)(1)(B).)

However, by its own terms, the new FEHA section does not apply “to a negotiated settlement agreement to resolve an underlying claim under this part that has been filed by an employee in court, before an administrative agency, in an alternative dispute resolution forum, or through an employer’s internal complaint process.” (Gov. Code, § 12964.5, subd. (d)(1).) The term “negotiated” is defined to mean “that the agreement is voluntary, deliberate, and informed, the agreement provides consideration of value to the employee, and that the employee is given notice and an opportunity to retain an attorney or is represented by an attorney.” (Gov. Code, § 12964.5, subd. (d)(2).)

While the scope of this exclusion has not yet been litigated, it unfortunately appears to mean that non-disparagement provisions are still permitted in employment settlements that are negotiated by attorneys, subject to the limitations discussed below. Employers are only restricted in circumstances where an employee is representing herself in severance negotiations. In such a situation, the employer may not prohibit the employee from disclosing information about unlawful acts in a severance agreement unless the agreement includes a monetary payment to the employee and the employee is given the opportunity to be represented and the employee clearly understood the terms of the agreement and was given time to read and consider it. This is a far cry from taking non-disparagement provisions off the table entirely, although it is a step in the right direction.

The second relevant statute that all employment attorneys should know is Code of Civil Procedure section 1002, subdivision (a)(1), which has been on the books since 2017. Under this provision, if a “civil action” involves an act that “may be prosecuted as a felony sex offense,” such as a workplace rape, you may not agree to confidentiality. (Code Civ. Proc., § 1002, subd. (a)(1).) Not only would such an agreement be “void as a matter of law,” but an attorney who demands such an agreement could be subject to disciplinary action by the State Bar. (Code. Civ. Proc., § 1002, subds. (d) & (e).) The statute does not preclude an agreement to protect the victim’s identity or medical information about the victim.

It is unclear whether Code of Civil Procedure section 1002 prohibits confidentiality in pre-litigation settlement agreements, or applies only to settlement agreements in cases that have already been filed. I have participated in some mediations in which the defendant has insisted the provision does not apply to pre-litigation settlements. However, given the potential for State Bar disciplinary action against an attorney who proposes confidentiality when a felony sex offense is alleged to have occurred, it seems risky to agree to a confidentiality provision even in a pre-litigation settlement agreement.

It is important to note that a non-disparagement provision broadly prohibiting the plaintiff from saying anything negative about the defendant is tantamount to an NDA. For example, if the plaintiff were to say, “The president of the defendant-company sexually assaulted me,” this would violate an agreement not to say anything non-disparaging about the company. Accordingly, if the defendant proposes a non-disparagement provision in a case involving allegations of felony sexual assault, it must be eliminated entirely on the basis that it violates Code of Civil Procedure section 1002, or contain a carve-out making clear that the plaintiff may continue to speak about factual information related to her claims. Similarly, a “no publicity” clause that prohibits you or your client from speaking to the media about the allegations of her case would also likely violate section 1002 because the statute prohibits any settlement provision “that prevents the disclosure of factual information related to the action.”

The third relevant statute is the revised Code of Civil Procedure section 1001, subdivision (a), which prohibits non-disclosure agreements if a filed administrative charge or lawsuit involves: 1) any act of sexual assault not covered by Code of Civil Procedure section 1002, subdivision (a), 2) an act of sexual harassment, or 3) an act of workplace harassment or discrimination, or retaliation against a person for reporting harassment or discrimination. The parties in such cases may still agree to keep the amount of the settlement confidential. At the plaintiff’s request, the parties may also agree to a provision that shields the plaintiff’s identity.

Unlike Code of Civil Procedure section 1002, which is ambiguous about whether it applies to pre-litigation settlement agreements, section 1001 explicitly applies only to the settlement of a claim that has been “filed” in court or an administrative action. This means that NDAs and non-disparagement provisions are fair game in the settlement of pre-litigation disputes, and an employer may request them as a condition of settlement (subject to the two statutes discussed above).

Because the restrictions on NDAs and non-disparagement provisions apply only to filed actions (assuming your case does not involve allegations that could be charged as felony sexual assault), you should discuss with your client at the outset of the representation whether they would agree to confidentiality and non-disparagement in exchange for a higher settlement amount. If the answer is “yes,” then you should preserve your client’s leverage and not file an administrative charge unless there is a compelling reason to do so (e.g., the statute of limitations is about to run and you have not secured a tolling agreement pending settlement discussions). If the client wants to take confidentiality and non-disparagement off the table, it might be worthwhile to file an administrative charge so that it is a non-issue during settlement discussions.

If you find yourself settling a case in which confidentiality and non-disparagement provisions are permitted, there are several ways to limit the provisions to benefit your client. For example, any non-disparagement provision must clearly identify the people or entities that your client cannot disparage. Very often, a non-disparagement provision will state that your client agrees not to say anything disparaging about the “Releasees.” The term “Releasees” almost always includes not only the company being sued, but also all of its officers, agents, affiliates, associates, partners, subsidiaries, parents, and so on. If your client does not know who is an “affiliate” of the company, she has no way of knowing whether she is violating the settlement agreement or not. For this reason, a non-disparagement provision should clearly identify by name the people and entities that may not be disparaged.

Non-disparagement and confidentiality provisions must also permit your client to disclose information in response to legal process and to government employees acting in their official capacities, such as an EEOC investigation. You can also request a carve-out so that confidential information can be disclosed to your client’s family members, attorneys, tax advisors, financial advisors, medical providers, mental health providers and clergy. The settlement agreement should also contain a provision stating that the agreement is admissible in any proceeding to enforce its terms, and the parties agree to waive mediation confidentiality in accordance with Evidence Code sections 1123 and 1124.

No rehire provisions are illegal

Back in the day, settlement agreements almost always included a provision stating that the employee agreed never to apply to work for the employer again. Effective January 1, 2020, however, these “no rehire” provisions are illegal. (See Code Civ. Proc., § 1002.5, subd. (a).) Significantly, the new law does not prohibit the employer from asking the employee to resign as a condition of settlement. (Id., § 1002.5, subd. (b)(1)(A).) Defendants continue occasionally to include “no rehire” provisions in settlement agreements. Just cite Code of Civil Procedure section 1002.5, subdivision (a) and they should back down.

Neutral reference

The settlement agreement should discuss how any inquiries about the plaintiff will be handled, including who will handle such inquiries and what they will be allowed to say. Most employers will agree to include a provision stating that any inquiries about the plaintiff’s employment will be submitted to the Human Resources Director, who will disclose only the plaintiff’s position and dates of employment.

Restraints on trade, non-competes are prohibited

Employers sometimes include provisions in a settlement agreement purporting to limit your client’s ability to work in their chosen profession. These provisions might take the form of a provision stating that your client will not solicit any of the employer’s customers, or that your client will not use any of the employer’s proprietary or confidential information. California is very protective of employees’ abilities to make a living, and non-solicitation and non-compete provisions are largely unenforceable. Under California Business & Professions Code section 16600, “every contract by which anyone is restrained from engaging in a lawful profession, trade, or business of any kind is to that extent void.”

There are many examples of cases in which the court has used Business & Professions Code section 16600 to strike down restraints on trade in employment agreements. (See, e g., Brown v. TGS Mgmt. Co., LLC (2020) 57 Cal.App.5th 303, 316 [confidentiality provisions in employment contract were overly restrictive and effectively prohibited former employee from working in the securities industry]; Edwards v. Arthur Andersen LLP, 44 Cal.4th 937, 948 (2008) [time-limited anti-solicitation and non-compete clauses in employment agreement void because they restricted employee’s ability to “practice his accounting profession”].) Accordingly, if the employer tries to insert non-compete or non-solicitation provisions in the settlement agreement, you will have ample ammunition to push back against these provisions.

Inclusion of arbitration provisions

Defendants sometimes insist on provisions stating that any dispute over the settlement agreement will be resolved through arbitration. Arbitration is a matter of contract, and there is nothing preventing your client from agreeing to arbitrate disputes. However, many of our clients will not be in the position financially to afford to pay for arbitration. Accordingly, if you are going to agree to arbitration, it may be worthwhile to insist that the employer pay for it, just as the employer would be required to pay for the arbitration of FEHA claims. (Armendariz v. Found. Health Psychcare Servs., Inc. (2000) 24 Cal.4th 83, 113 [employer that requires arbitration of FEHA claims must pay “all types of costs that are unique to arbitration”].)

Liquidated-damages provisions

Defendants in employment cases often insist on the inclusion of a liquidated-damages provision for the plaintiff’s breach of the settlement terms, perhaps most commonly for blabbing about the settlement amount. If you negotiate non-monetary terms in advance, one bullet point on your term sheet should be “no liquidated damages for any breach of any provision of the settlement agreement.” But if you find yourself forced to agree to liquidated damages, there are still some helpful tips for limiting your client’s exposure for breaching the agreement.

First, you can limit the amount of liquidated damages by arguing that the very high amount proposed by the defendant constitutes an “unenforceable penalty” that a court would likely invalidate. (See, e.g., Purcell v. Schweitzer (2014) 224 Cal.App.4th 969, 974 [invalidating liquidated damages provision in a settlement agreement because it bore “no reasonable relationship to the range of actual damages that the parties could have anticipated would flow from a breach”].) Generally speaking, I would hesitate to agree to a liquidated damages provision that was more than 10% of the settlement amount going to my client.

Second, you should include language in the liquidated-damages provision to protect your client in the case of a breach. For example, you may want to spell out that liquidated damages are payable only after a court enters final judgment that the plaintiff has breached the relevant provisions of the settlement agreement, and that the employer has the burden to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that plaintiff breached. You may also want to make clear that any breach or payment of liquidated damages will not affect the continuing enforceability of the remainder of the agreement. And finally, you should resist any efforts to hold your client liable for the acts of third parties, such as a spouse who discloses information in violation of a confidentiality provision.

Structured-settlement protections

The pandemic has resulted in far more defendants claiming financial distress. Once you evaluate the defendant’s financial records, you might agree to a structured settlement, with payments made in installments over months or even years. There are a variety of different provisions that may be prudent to include if you are inclined to agree to a structured settlement.

For example, your client’s release of claims should not be immediate, but should explicitly be contingent on the defendant’s payment of the final installment. Asking that the owner of the defendant-company provide a personal guarantee of the settlement amount could help protect against default. An acceleration clause that states the entire settlement amount immediately becomes due and owing if the defendant misses a payment could be helpful if you need to start collections proceedings against the defendant and want to obtain a judgment for the entire amount still owed on the settlement.

In exchange for an agreement to a structured settlement, you might also insist that the defendant provide you with a stipulated judgment for an amount higher than the settlement less any payments made. This will incentivize the defendant to make timely payments; if it does not, the defendant will owe more than the settlement amount. If the defendant misses a payment, you will be entitled to seek entry of the stipulated judgment and immediately begin collections proceedings rather than having to litigate the defendant’s breach to obtain a judgment.

If you plan to ask for a stipulated judgment, be sure to read Vitatech Internat., Inc. v. Sporn (2017) 16 Cal.App.5th 796, which invalidated a stipulated judgment for breach of a settlement agreement because the amount of the stipulated judgment was too high and held to be an unenforceable penalty.

To maximize the likelihood that the court will enforce a stipulated judgment, consider stating that the settlement amount represents a discounted amount that the plaintiff offered to encourage timely payments; that the stipulated judgment amount represents the amount of damages arrived at after a mediation (or lengthy settlement negotiations with the exchange of information); the defendant offered the stipulated judgment to compensate plaintiff for the loss of use of the money and reasonable costs should defendant default; and the stipulated judgment does not impose an unenforceable penalty.

Ensuring that the court retains jurisdiction

Many settlement agreements provide that the parties agree that the court will retain jurisdiction to enforce the terms of the settlement pursuant to Code of Civil Procedure section 664.6. This is an important settlement term that will make your life easier if the defendant defaults: Section 664.6 provides a summary procedure by which the trial court may specifically enforce an agreement settling pending litigation without the need to file a second lawsuit. (Kirby v. Southern Cal. Edison (2000) 78 Cal.App.4th 840, 843.)

A judge hearing a section 664.4 motion may receive evidence, determine disputed facts, and enter the terms of a settlement agreement as a judgment. (Osumi v. Sutton (2007) 151 Cal.App.4th 1355, 1360.) In making its determination, the trial judge may adjudicate the motion upon declarations alone. (Corkland v. Boscoe (1984) 156 Cal.App.3d 989, 994.)

Beware, however, when requesting that the court dismiss a case pursuant to a settlement agreement that contains a section 664.6 provision. In Mesa RHF Partners, L.P. v. City of Los Angeles (2019) 33 Cal.App.5th 913, the court held that the trial court properly found that it was without section 664.6 jurisdiction because the request for dismissal and retention of jurisdiction was signed only by counsel, and not by the parties as required by the plain language of the statute. (Code Civ. Proc., § 664, subd. (a) [“If requested by the parties, the court may retain jurisdiction over the parties to enforce the settlement until performance in full of the terms of the settlement.”] [emphasis added].)

Accordingly, if you have settled a case and would like the court to retain jurisdiction, do not use the Judicial Council form (CIV-100) to dismiss your claims. Instead, file a stipulation for dismissal that is signed by the attorneys and the parties requesting that the court retain jurisdiction under Code of Civil Procedure section 664.6.

Conclusion

There are many potential pitfalls in settlement agreements, but you can minimize the likelihood of falling into any of them by negotiating non-monetary terms before you agree to a number. Familiarize yourself with the tax implications of settlement allocations, and limit your client’s tax indemnification of the employer as much as possible.

Review the three statutes regarding NDAs and non-disparagement provisions, and seek to limit such provisions even when they are permitted. Restraints on trade and “no rehire” provisions are unlawful and should be off the table. Liquidated damages provisions should be limited.

If there is a structured settlement, insist on safeguards to protect your client from default. And finally, follow the proper procedures for the court to retain jurisdiction to enforce the settlement.

Now that you have made it to the end of this article, you should be well-prepared to push back against any illegal or unfavorable settlement terms the employer throws at you, even if it is after midnight.

Lauren Teukolsky

Lauren Teukolsky is the owner of Teukolsky Law, which provides legal representation exclusively to employees. She was recently named to the 2022 Top 50 Women Lawyers in Southern California List. Ms. Teukolsky received a CLAY award in 2016 for her work on a complex wage-and-hour class action against Walmart on behalf of warehouse workers in the Inland Empire. She received her J.D. from UCLA School of Law and her B.A. from Harvard College. She can be reached at lauren@teuklaw.com.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine