Comparing Title VII discrimination claims and FEHA claims

Both prohibit discrimination, but differences include coverage, procedures, remedies, and standards

When employees experience workplace discrimination, they may seek remedies under various laws. Two major legal frameworks for such claims in California are Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (federal law) and the Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA) (California state law, Gov. Code, § 12900 et seq.) Title VII and the FEHA use similar language, attempting to eliminate the same conduct. (See Price v. Civil Service Comm’n (1980) 26 Cal.3d 257, 271.) While both prohibit discrimination, they differ in several important ways, including coverage, procedures, remedies, and standards. Understanding these differences is crucial for attorneys representing employees navigating employment disputes.

Overview of Title VII

Title VII is a federal law that prohibits employment discrimination based on:

Race

Color

Religion

Sex (including pregnancy, sexual orientation, and gender identity)

National origin (42 USC § 2000e-2)

It is noteworthy to indicate that race and color, while often considered synonymous, are distinct concepts. Both are listed separately as protected categories in Title VII. Thus, although such claims are rare, the color of one’s skin – as opposed to race – may form the basis for a discrimination claim, even if alleged against a member of the same race. (Walker v. Secretary of Treasury, I.R.S. (1989) 713 F. Supp. 403, 405 [claim that dark-skinned black supervisor discriminated against light-skinned black employee on basis of latter’s skin color is actionable under Title VII]; Williams v. Wendler (7th Cir. 2008) 530 F. 3d 584, 587.) Title VII applies to employers with 15 or more employees, as well as employment agencies, labor organizations, and certain federal, state, and local governments. (42 USC § 2000e-2(a)-(d); see also 42 USC § 2000e-16.) Title VII also applies to persons who have resigned or been fired and who allege discrimination or retaliation. (Robinson v. Shell Oil Co. (1997) 519 US 337, 345-346.)

Claims under Title VII are generally administered by the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). Before filing a lawsuit, a claimant must first file a charge with the EEOC and receive a “right-to-sue” letter. It is important to note that individuals complaining of Title VII employment discrimination may file charges with either the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) or a state or local fair employment agency. (See 42 USC § 2000e-5(b), (c), (e).) This includes the California employee having the right in California to file an action against the employer under California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act, whose advantages to the employee are more fully discussed below.

Overview of FEHA

The Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA) is California’s primary anti-discrimination law. FEHA prohibits discrimination based on a broader range of protected characteristics than Title VII, including but not limited to:

Race

Color

Religion

Sex, gender, gender identity, gender expression

Sexual orientation

Marital status (Gov. Code, § 12940(a))

National origin

Ancestry

Disability (physical and mental)

Medical condition

Age (40 and over)

Genetic information

Military or veteran status (Gov. Code, § 12926(k))

(See Gov. Code, § 12926 for definitions.)

Importantly, FEHA applies to employers with five or more employees – a lower threshold than Title VII. Claims are handled by the California Civil Rights Department (CRD) (formerly the Department of Fair Employment and Housing, or DFEH). (Gov. Code, § 12926(d).)

This expansive coverage allows FEHA claimants to pursue legal remedies for discriminatory acts that may not be actionable under federal law. For example, discrimination based on a medical condition like cancer is explicitly covered under FEHA but not under Title VII.

Time limits (Statutes of limitation)

Title VII:

A charge must be filed with the EEOC within 180 days of the alleged unlawful employment action. (42 USC § 2000e-5(f)(1))

After receiving the right-to-sue letter, the claimant has 90 days to file a lawsuit in federal court. (42 USC § 2000e-5(f)(1))

FEHA:

As of January 1, 2020, the deadline to file with the CRD is three years from the date of the alleged unlawful act (an extension from the previous one-year limit).

After receiving a right-to-sue notice from the CRD, the claimant has one year to file a lawsuit in California state court.

Key differences between Title VII and FEHA

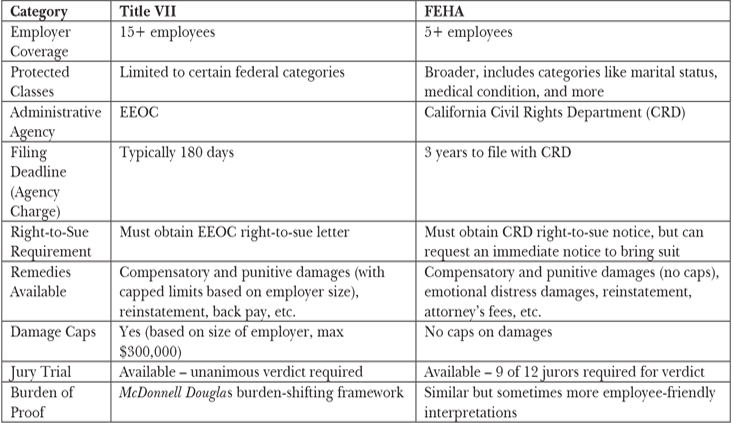

The included chart has been compiled to demonstrate the key differences between Title VII claims and FEHA claims.

Practical implications

Broader protections: Employees who might not qualify for federal protection under Title VII often have viable claims under FEHA, especially for categories like marital status, medical condition, or smaller employers.

Higher potential damages: FEHA does not impose statutory caps on damages, unlike Title VII, where caps can significantly limit recovery.

Longer filing period: FEHA allows employees more time (up to three years) to file administrative complaints compared to Title VII’s stricter deadlines.

Procedural flexibility: California courts often interpret FEHA more liberally in favor of employees, making it a stronger avenue for certain plaintiffs.

Unanimous verdict: A unanimous jury verdict is not required in state court.

Why filing under FEHA is often better than under Title VII

For attorneys representing employees in California, choosing to pursue a claim under FEHA rather than Title VII can offer a number of strategic and practical benefits. There are many key reasons why filing a claim under FEHA is often the more advantageous route for California-based claimants.

As discussed above, by providing protection for more characteristics, FEHA offers recourse in a wider array of discriminatory scenarios, especially those involving evolving identities and societal norms that may not yet be fully protected under federal law.

Broader definitions

California courts interpret the provisions of FEHA more liberally than federal courts do with Title VII. Terms such as “adverse employment action,” “harassment,” and “disability” have broader meanings under FEHA, making it easier for plaintiffs to meet their burden of proof. For example, while federal courts may require a “materially adverse” action for a retaliation claim under Title VII, California courts may find liability for less severe or subtle retaliatory actions under FEHA. (42 USC § 2000e-2(a)(1); see Terry v. Gary Comm. School Corp. (2018) 910 F3d 1000, 1005 – employer’s action is materially adverse where it is more disruptive than mere inconvenience or alteration of job responsibilities.)

Individual liability

FEHA also allows for individual liability for certain forms of harassment. Under Title VII, only employers (as entities) can be held liable – not individual supervisors or coworkers. Under FEHA, supervisors and managers can be personally sued for harassment, although not for discrimination. (Gov. Code, § 12940, subd. (j)(3).) The statutory definition of “employer” includes persons “acting as an agent of an employer.” (Gov. Code, § 12926, subd. (d).) But this was intended “to ensure that employers will be held liable if their supervisory employees take actions later found discriminatory.” (Reno v. Baird (1998) 18 Cal.4th 640, 647.) This distinction can be strategically important. Naming an individual as a defendant can:

Create settlement pressure

Strengthen negotiating leverage

Prevent removal to federal court due to diversity jurisdiction

Do also note that supervisors and coworkers may not be held personally liable for retaliation under the FEHA. (Jones v. Lodge at Torrey Pines Partnership (2008) 42 Cal.4th 1158, 1173.)

Greater damages and additional remedies

Under Title VII, compensatory and punitive damages are capped based on the size of the employer:

$50,000 (for employers with 15-100 employees)

$100,000 (101-200 employees)

$200,000 (201-500 employees)

$300,000 (501+ employees)

(42 U.S.C. § 1981a(b)(3).)

In contrast, FEHA imposes no such caps. Plaintiffs can recover unlimited compensatory and punitive damages, making the potential recovery far greater, particularly in severe cases involving emotional distress or intentional misconduct. (Commodore Home Systems, Inc. v. Superior Court (1995) 32 Cal.App.4th 296.)

FEHA allows courts to impose broader injunctive remedies than Title VII. These include but are not limited to reinstatement, modification of workplace policies, mandatory training, and other systemic reforms that extend beyond the individual plaintiff’s situation. (See Harris v. City of Santa Monica (2013) 56 Cal.4th 203.)

Longer statute of limitations

The timeframe to file a claim can be pivotal in employment litigation. FEHA offers significantly more generous deadlines as discussed above.

More favorable legal procedures in state court

Filing under FEHA typically keeps the case in California state court, which is often more plaintiff-friendly than federal court. State courts:

Are less likely to grant summary judgment;

Allow broader discovery;

May have more diverse jury pools;

Tend to interpret anti-discrimination laws more expansively.

(Nazir v. United Airlines, Inc. (2009) 178 Cal.App.4th 243.)

Because FEHA is a state law, cases based solely on FEHA cannot be removed to federal court on the basis of a federal question. This gives plaintiffs greater control over forum selection, which can be crucial for case strategy.

Quicker right-to-sue letter

Claimants under FEHA can immediately request a right-to-sue notice from the CRD and bypass any investigation or mediation, allowing them to move swiftly into litigation.

By contrast, the EEOC typically undertakes an investigation process before issuing a right-to-sue letter, which can take several months or even longer.

The CRD, although not without delays, often has less backlog than the EEOC. The ability to initiate litigation quickly can be critical in preserving evidence and witness testimony.

More lenient legal standards for plaintiffs

California courts apply a more liberal standard for discrimination and harassment. Under FEHA, a plaintiff can prove discrimination with circumstantial evidence and does not need to follow the McDonnell Douglas burden- shifting framework unless the employer offers a legitimate, nondiscriminatory reason. (See Harris v. City of Santa Monica (2013) 56 Cal.4th 203.)

Harassment under FEHA is assessed based on whether the conduct “would have interfered with a reasonable employee’s work performance and would have seriously affected the psychological well-being of a reasonable employee.” (Miller v. Department of Corrections (2005) 36 Cal.4th 446.) This is more plaintiff-friendly than the federal “severe or pervasive” standard. (Harris v. Forklift Systems (1993) 510 U.S. 17.)

Substantial motivating factor standard

FEHA recognizes mixed-motive discrimination where an illegal factor was a “substantial motivating reason” for the adverse action, even if other factors were also involved. (Harris v. City of Santa Monica (2013) 56 Cal.4th 203.)

Title VII allows for similar claims, but the remedies may be more limited. Under the Civil Rights Act of 1991, an employer can limit the remedies available, but not avoid liability altogether, by demonstrating that although discrimination played a motivating part in the discriminatory action, the employer would have taken the same action even in the absence of discrimination. (42 USC § 2000e-5(g)(2)(B).)

Recognition of intersectional claims

California courts are more likely to acknowledge intersectional discrimination, such as bias based on a combination of race and gender. FEHA’s structure and case law allow for multi-faceted discrimination theories that may not be adequately addressed under Title VII. (See McGinest v. GTE Serv. Corp. (2004) 360 F.3d 1103.)

Some additional protections only available under FEHA

Associational discrimination

FEHA prohibits discrimination based on an employee’s association with a person in a protected class – for example, retaliation against an employee for advocating on behalf of a disabled coworker. (Gov. Code, § 12926, subd. (o); § 12940, subd. (a).) Title VII does not clearly recognize this as a cause of action.

Family responsibilities and lactation accommodation

FEHA and related California laws require employers to provide lactation accommodations and protect employees against family responsibilities discrimination, areas where federal law offers limited coverage.

Favorable state court forum

As most of us know or will come learn at some point in our careers, pleading standards in state court are more lenient than in federal court. (See Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly (2007) 550 U.S. 544; Ashcroft v. Iqbal (2009) 556 U.S. 662.) Judges and juries in California tend to be more progressive, especially in urban counties. As to motions for summary judgment, which are inevitable in employment cases, they are less frequently granted in state court cases. (See Nazir v. United Airlines, Inc. (2009) 178 Cal.App.4th 243.) This environment can make it easier for plaintiffs to reach trial and secure relief.

Leverage during negotiations

The threat of unlimited damages, individual liability, and access to a favorable forum provides plaintiffs with significant negotiation leverage in settlement discussions. Employers face more exposure under FEHA, incentivizing early resolution and higher settlement offers.

LGBTQ+ discrimination claims are often stronger under FEHA than Title VII

LGBTQ+ employees facing workplace discrimination are protected under both federal and state laws. Federally, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibits employment discrimination “because of… sex.” In Bostock v. Clayton County (2020) 590 U.S. 644, the U.S. Supreme Court held that discrimination based on sexual orientation or gender identity is a form of sex discrimination under Title VII. Title VII’s protection for LGBTQ+ individuals was judicially recognized in Bostock, and the ruling left many open questions about its scope, such as religious exemptions and application to transgender employees in specific contexts. (See Religious Sisters of Mercy v. Becerra (2022) 55 F.4th 583.)

In California, the Fair Employment and Housing Act (FEHA) (Gov. Code, §§ 12900-12996) has long provided more comprehensive, explicit protections for LGBTQ+ workers. For the key reasons discussed above, LGBTQ+ discrimination claims are generally better pursued under FEHA when both legal avenues are available.

Under Title VII, plaintiffs are often required to identify a similarly situated comparator who was treated more favorably. (See Texas Dept. of Community Affairs v. Burdine (1981) 450 U.S. 248.) This can be especially difficult in LGBTQ+ cases where a straight or cisgender “comparator” might not exist.

FEHA courts are more flexible, allowing plaintiffs to prove discrimination through context and circumstantial evidence without strict comparator requirements. (See Clark v. Claremont University Center (1992) 6 Cal.App.4th 639.)

Executive order 12250 poses risks for discrimination cases

On April 23, 2025, President Trump signed an Executive Order 12250 titled “Restoring Equality of Opportunity and Meritocracy.” An executive order aimed at restoring “equality of opportunity” and “meritocracy” may sound like positive steps toward fairness, but it poses serious risks for employment discrimination cases. Historically marginalized groups – such as women, racial minorities, and individuals with disabilities – often face barriers that pure “merit-based” metrics fail to account for.

Employers could feel emboldened to roll back inclusive hiring practices, claiming a renewed focus on “objective” standards. This shift could make it more difficult for plaintiffs to prove discrimination, as employers may argue that hiring decisions were simply based on merit, ignoring the broader context of unequal opportunity. Moreover, courts might interpret this executive emphasis as a policy signal, subtly influencing how they evaluate claims under Title VII or other civil rights laws. In short, the return to a so-called “meritocracy” risks entrenching existing inequalities under the guise of fairness, making it harder for victims of discrimination to find justice.

From this executive action, it appears that the federal government is attempting to weaken protections for employees and strengthen employers against employee actions. In contrast to what is occurring on the federal level with regard to Title VII, under FEHA, California continues to protect California employees and remains a stronger bullwork to protect the rights of California employees against wrongful acts by California employers.

Conclusion

While both Title VII and FEHA aim to protect employees from discrimination, FEHA provides broader protection, applies to smaller employers, and offers more generous remedies. Employees in California often benefit from filing under FEHA when possible. If the federal deadline has passed, FEHA may still be available. Always confirm both timelines before advising a client. In most cases involving California employees, FEHA offers broader, faster, and potentially more generous remedies than Title VII.

Meylin Alfaro

Meylin Alfaro is an associate at the Law Offices of Victor L. George and represents clients in all areas of personal injury and employment law. She completed her undergraduate studies at the University of California Riverside, and her law degree from the University of La Verne College of Law.

Copyright ©

2026

by the author.

For reprint permission, contact the publisher: Advocate Magazine